Inside China’s Hosting Ecosystem: 18,000+ Malware C2 Servers Mapped Across Major ISPs

Inside China’s Hosting Ecosystem: 18,000+ Malware C2 Servers Mapped Across Major ISPs

Published on

Jan 14, 2026

Threat hunting often begins with a single indicator, such as a suspicious IP address, a beaconing domain, or a known malware family. Looking at those indicators individually makes the underlying infrastructure easy to miss.

While analyzing malicious activity across Chinese hosting environments, we repeatedly observed the same networks and providers appearing across unrelated campaigns. Commodity malware, phishing operations, and state-linked tooling were often hosted side by side within the same infrastructure, even as individual IPs and domains changed.

This pattern exposes the limits of indicator-driven hunting. In this article, we examine how malicious infrastructure clusters and persists across Chinese ISPs when viewed at country scale, and why a host-centric approach makes these relationships visible.

Key Takeaways

Analysis of recent telemetry surfaced more than 18,000 active C2 servers distributed across 48 Chinese infrastructure providers.

C2 infrastructure dominates malicious activity (~84%), far exceeding phishing infrastructure (~13%), with open directories and public IOCs together contributing less than 4%.

China Unicom alone hosts nearly half of all observed C2 servers, with Alibaba Cloud and Tencent following, highlighting heavy concentration in large, high-capacity networks.

Tencent and Alibaba Cloud exhibit high phishing activity alongside C2 hosting, reflecting attacker preference for scalable, trusted cloud platforms.

A small set of malware families (Mozi, ARL, Cobalt Strike, Mirai, Vshell) accounts for most C2 activity, showing framework-driven, repeatable abuse.

IoT-based botnet infrastructure remains deeply entrenched, with Mozi's dominance reinforcing China's role in large-scale IoT C2 operations.

Chinese infrastructure supports both cybercrime and APT activity, with RATs, cryptominers, phishing frameworks, and state-linked malware coexisting in the same environments.

High-trust networks are actively abused, as China169 Backbone, CHINANET, and CERNET demonstrate exploitation of telecom and academic infrastructure.

How We Analyze Malicious Infrastructure at Country Scale

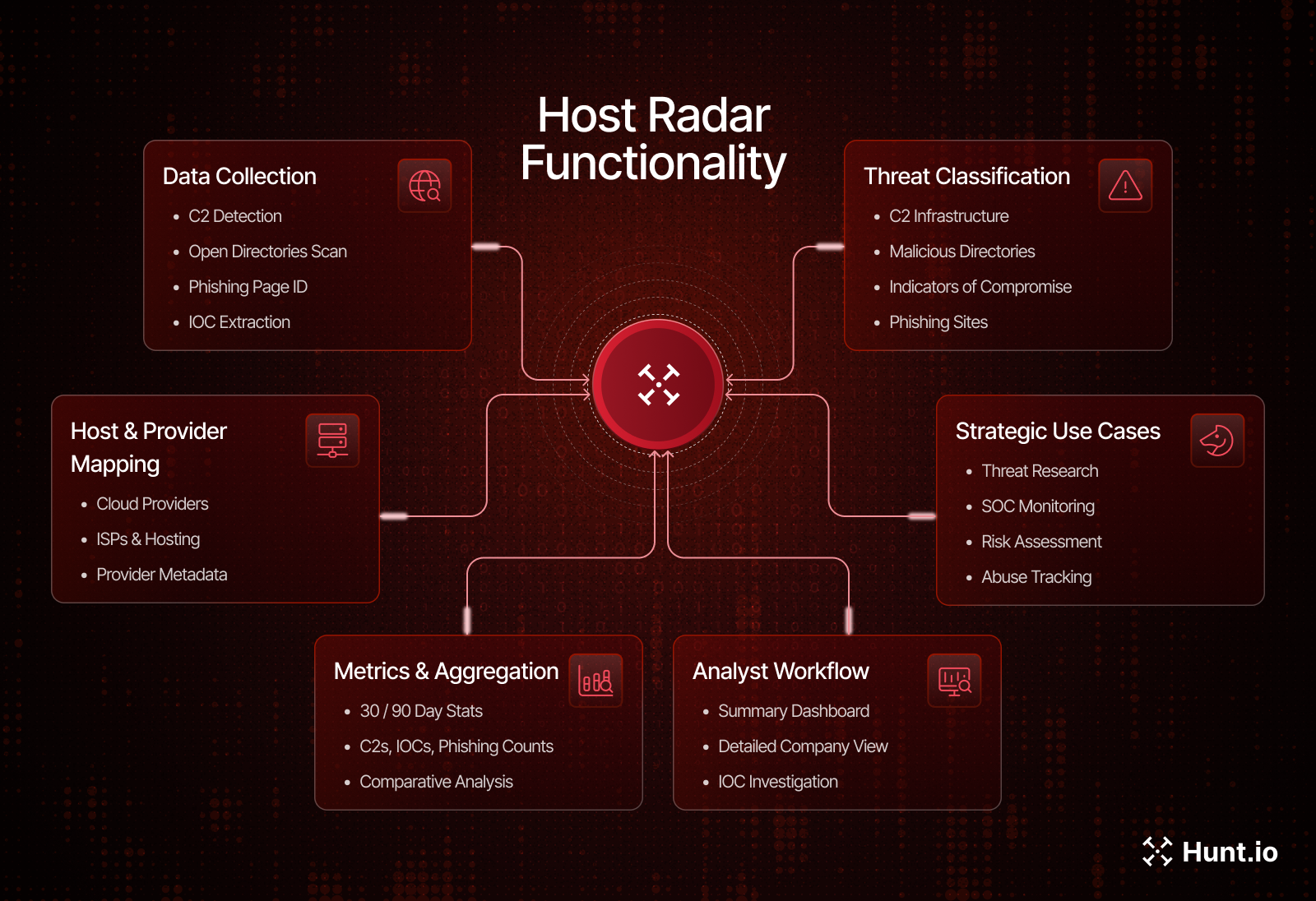

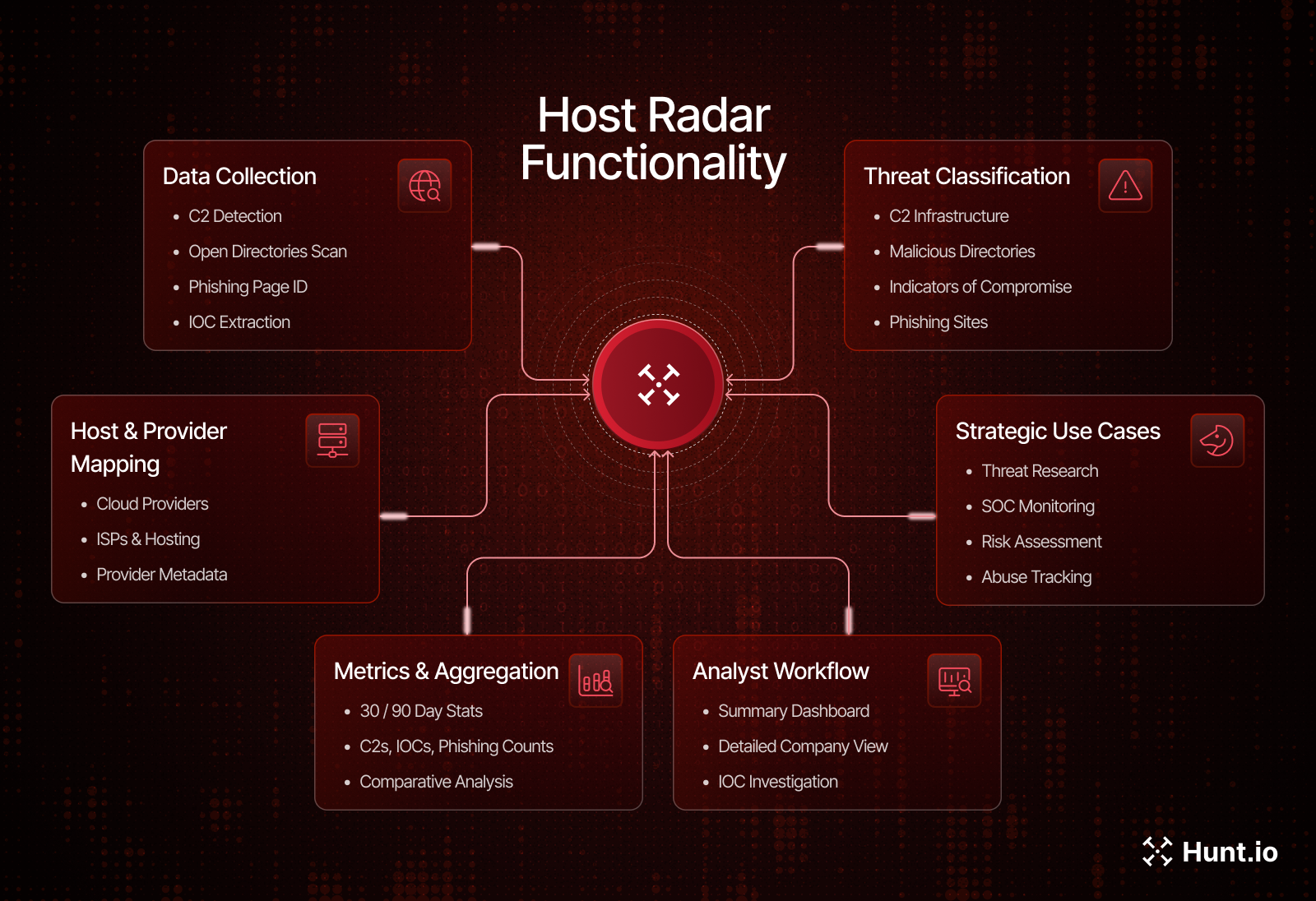

Host Radar was built to analyze infrastructure-level abuse at country and ISP scale by correlating command-and-control servers, phishing infrastructure, malicious open directories, and public IOCs back to the hosting providers and network operators where they reside.

Rather than treating each artifact as an isolated signal, Host Radar brings these datasets together into a single view. This makes it possible to see where malicious infrastructure consistently clusters, how it shifts over time, and which providers repeatedly support unrelated campaigns.

At this level, long-running abuse patterns become visible even when individual IP addresses or domains rotate frequently.

Host Radar Data Aggregation Model

To support this type of analysis, Host Radar operates as a centralized aggregation layer for malicious infrastructure telemetry. Signals from C2 detection, phishing identification, open directory scanning, and IOC extraction are combined and enriched with hosting, ASN, and network ownership context.

As illustrated in Figure 1, this unified view allows analysts to pivot across providers, networks, and time windows without relying on individual IP- or domain-level indicators, making country-scale infrastructure analysis practical and repeatable.

Figure 1. Host Radar functions as a central intelligence layer by aggregating C2 activity, malicious open directories, phishing pages, and IOCs, mapping them to hosting providers and ISPs.

Figure 1. Host Radar functions as a central intelligence layer by aggregating C2 activity, malicious open directories, phishing pages, and IOCs, mapping them to hosting providers and ISPs.With this aggregation in place, we can examine how malicious infrastructure is distributed across individual Chinese providers.

China’s Malicious Infrastructure Landscape by Provider

The Host Radar summary for the top five Chinese infrastructure providers shows both the volume and range of malicious activity observed across these organizations over the last three months.

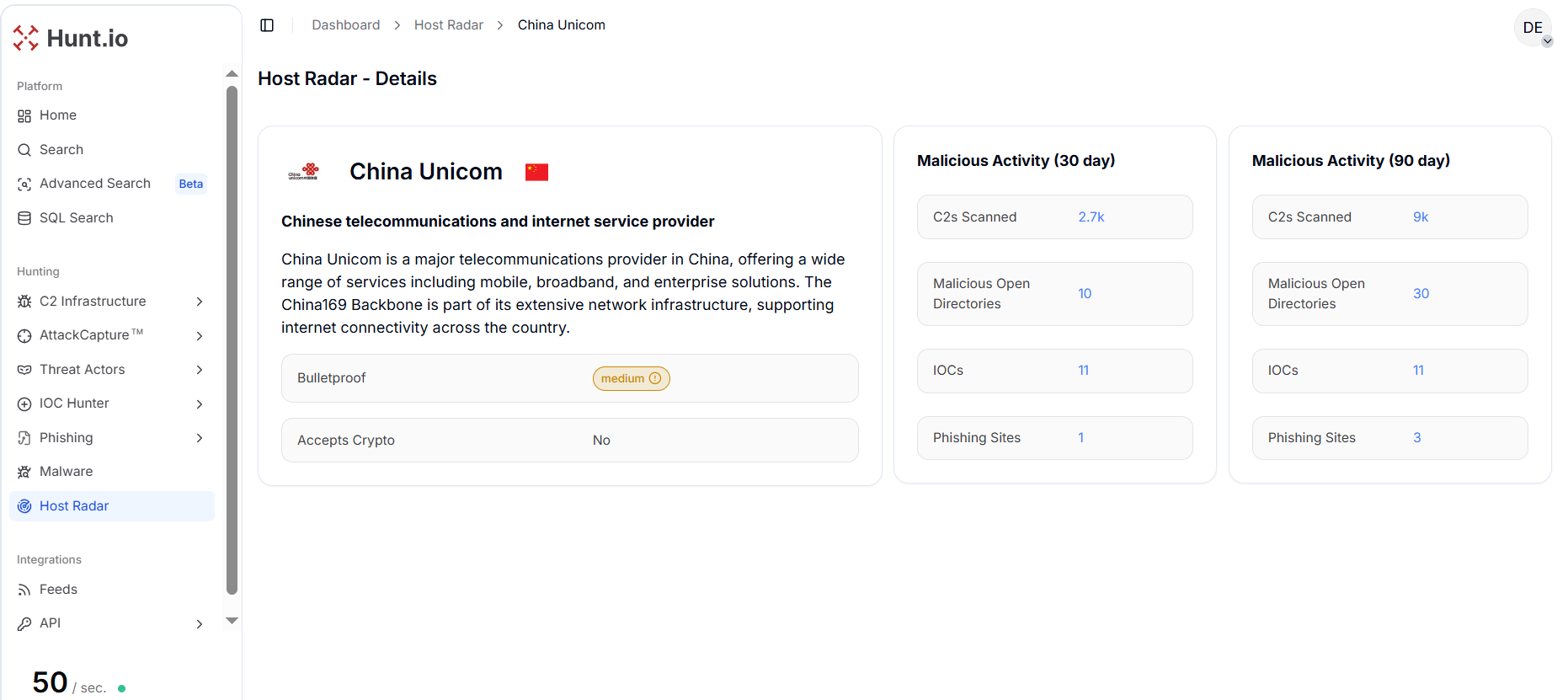

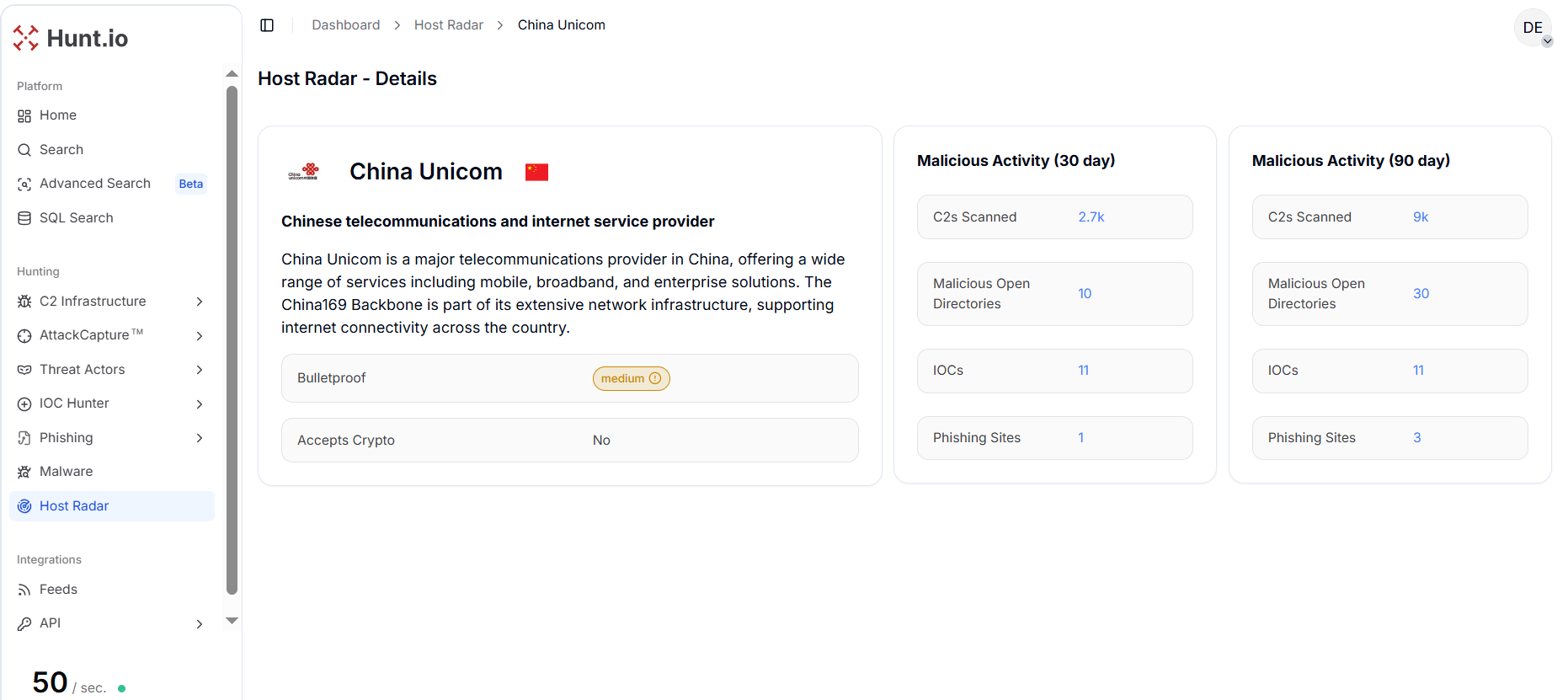

China Unicom, one of the largest telecommunications providers in China, exhibits the highest number of C2 servers, with 9,000 detected over 90 days, alongside 30 malicious open directories and 11 IOCs.

This single provider accounts for nearly half of all C2 infrastructure observed across Chinese hosting environments during the analysis period.

Figure 2. China Unicom - Host Radar Detailed View: Per-provider Host Radar breakdown for China Unicom, highlighting high-volume C2 activity and associated malicious artifacts.

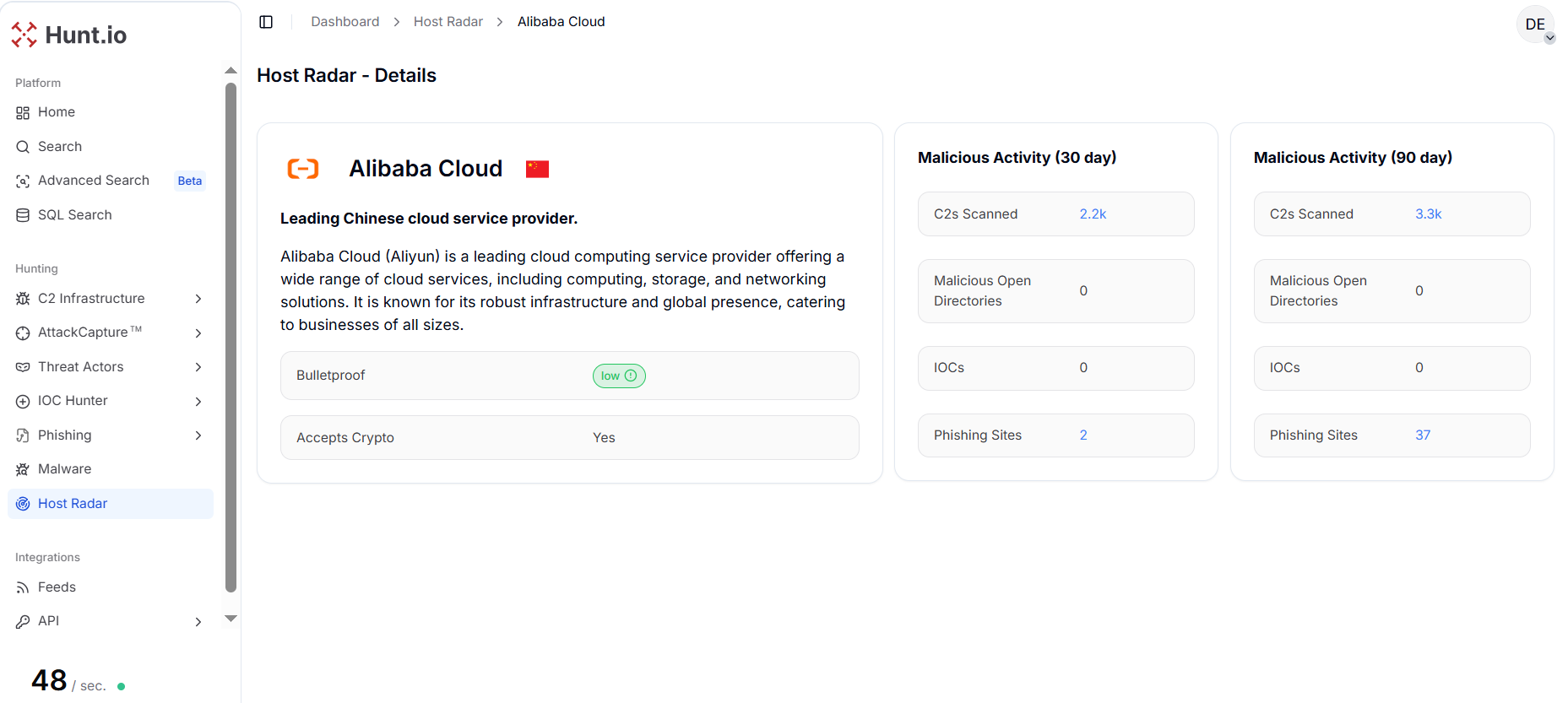

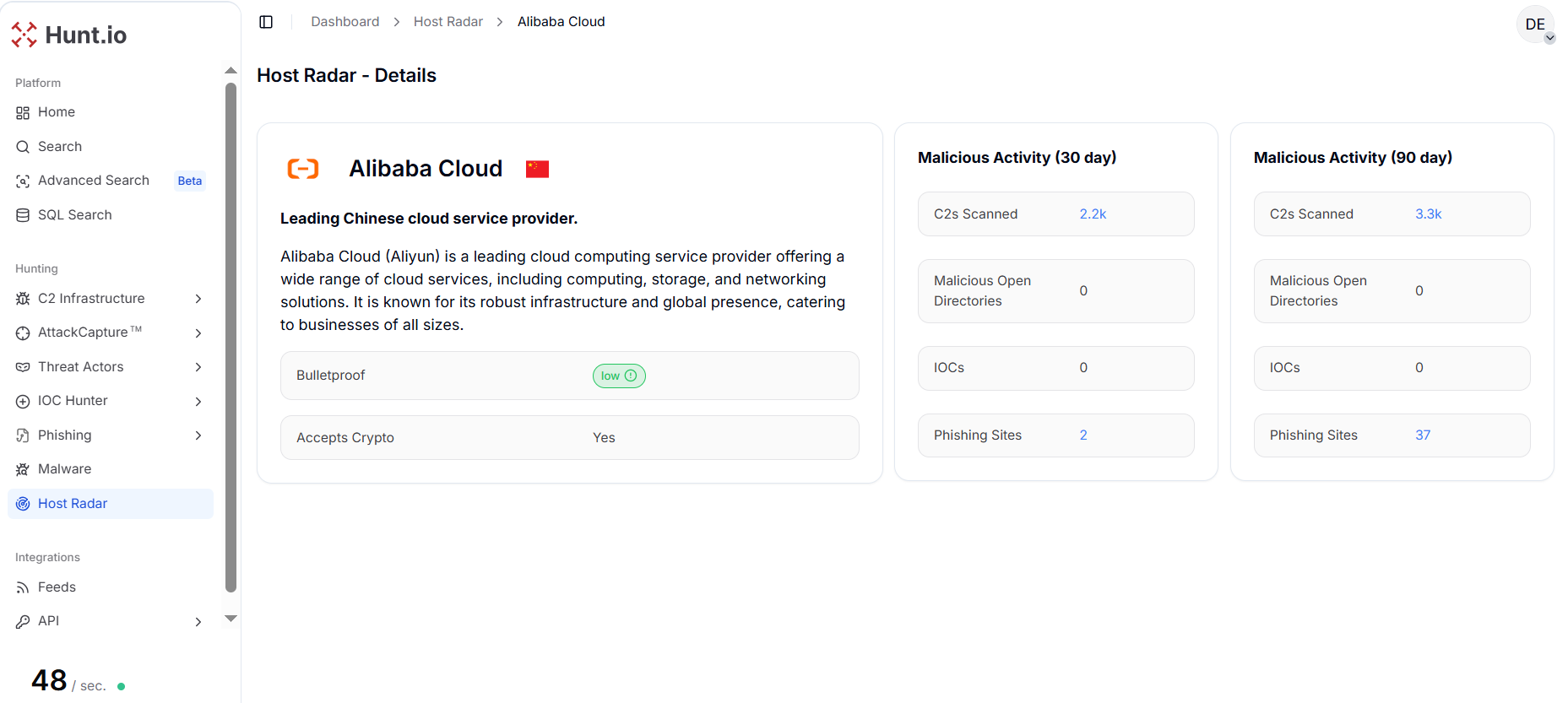

Figure 2. China Unicom - Host Radar Detailed View: Per-provider Host Radar breakdown for China Unicom, highlighting high-volume C2 activity and associated malicious artifacts.Similarly, Alibaba Cloud, a leading cloud service provider, shows significant C2 presence with 3,300 servers and 37 phishing sites, although it has zero open directories or IOCs, reflecting how cloud environments are leveraged primarily for resilient command-and-control operations rather than exposed artifacts.

This contrasts with telecom providers, where C2 infrastructure dominates but phishing and open directory exposure remain comparatively lower.

Figure 3. Alibaba Cloud - Host Radar Detailed View: Host Radar metrics for Alibaba Cloud, illustrating significant C2 usage and phishing activity within cloud-hosted environments.

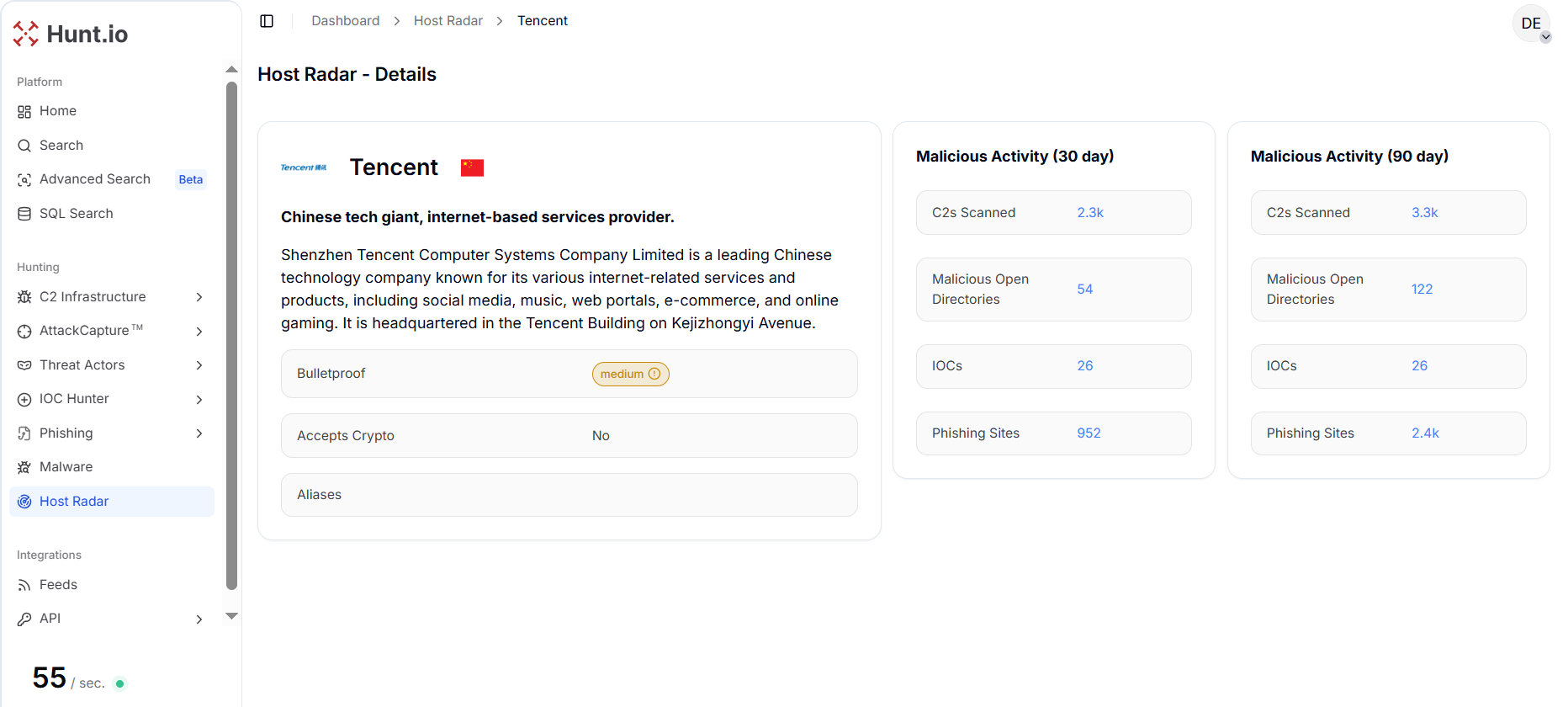

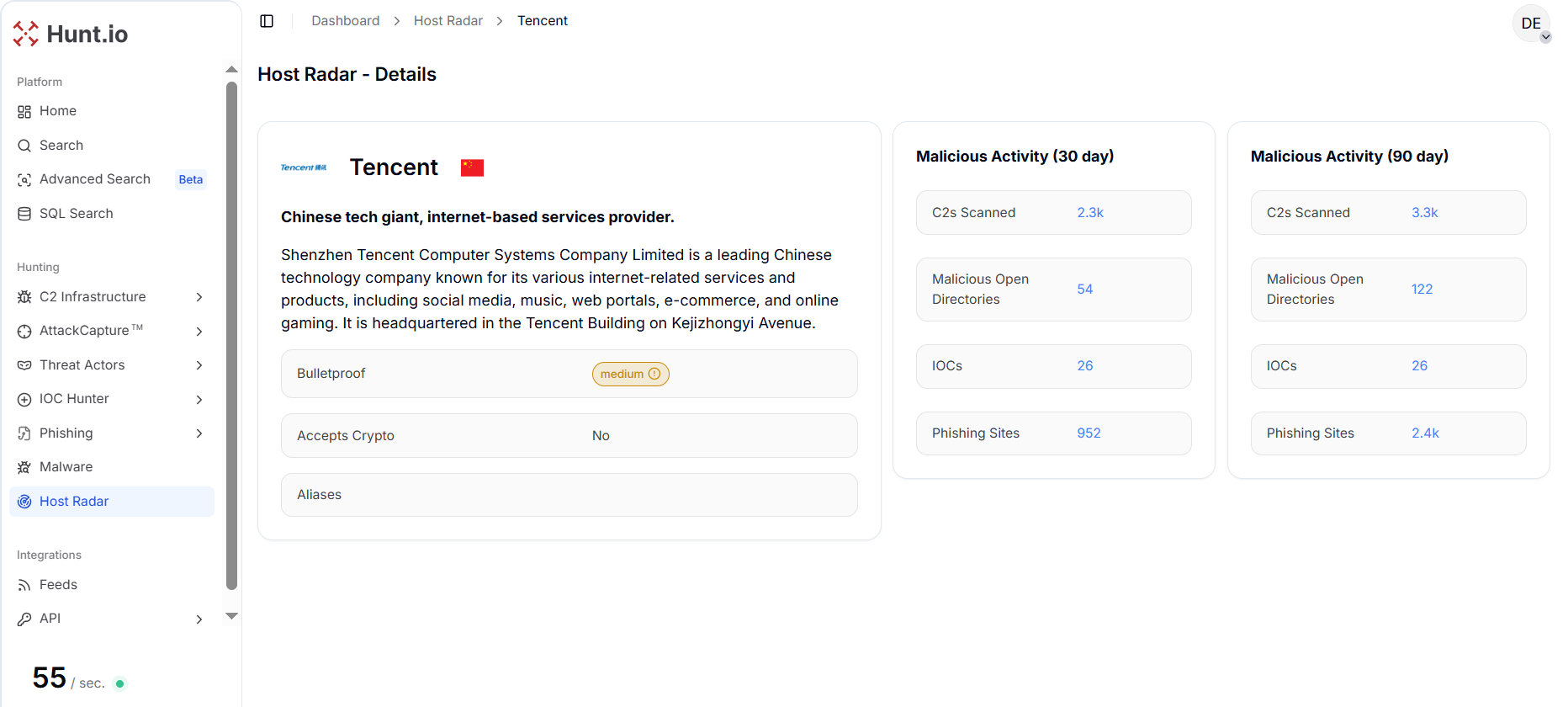

Figure 3. Alibaba Cloud - Host Radar Detailed View: Host Radar metrics for Alibaba Cloud, illustrating significant C2 usage and phishing activity within cloud-hosted environments.Tencent, the major Chinese technology conglomerate, demonstrates a more diverse malicious footprint. Over 90 days, it hosted 3,300 C2 servers, 122 open directories, 26 IOCs, and 2,400 phishing sites, indicating heavy abuse of its broad array of internet-facing services, including social media, gaming, and e-commerce platforms.

This matches what we see across the broader dataset, where phishing activity is concentrated in a small number of large cloud providers.

Figure 4. Tencent - Host Radar Detailed View: Detailed Host Radar view showing Tencent's diverse malicious footprint across C2 servers, phishing sites, open directories, and IOCs.

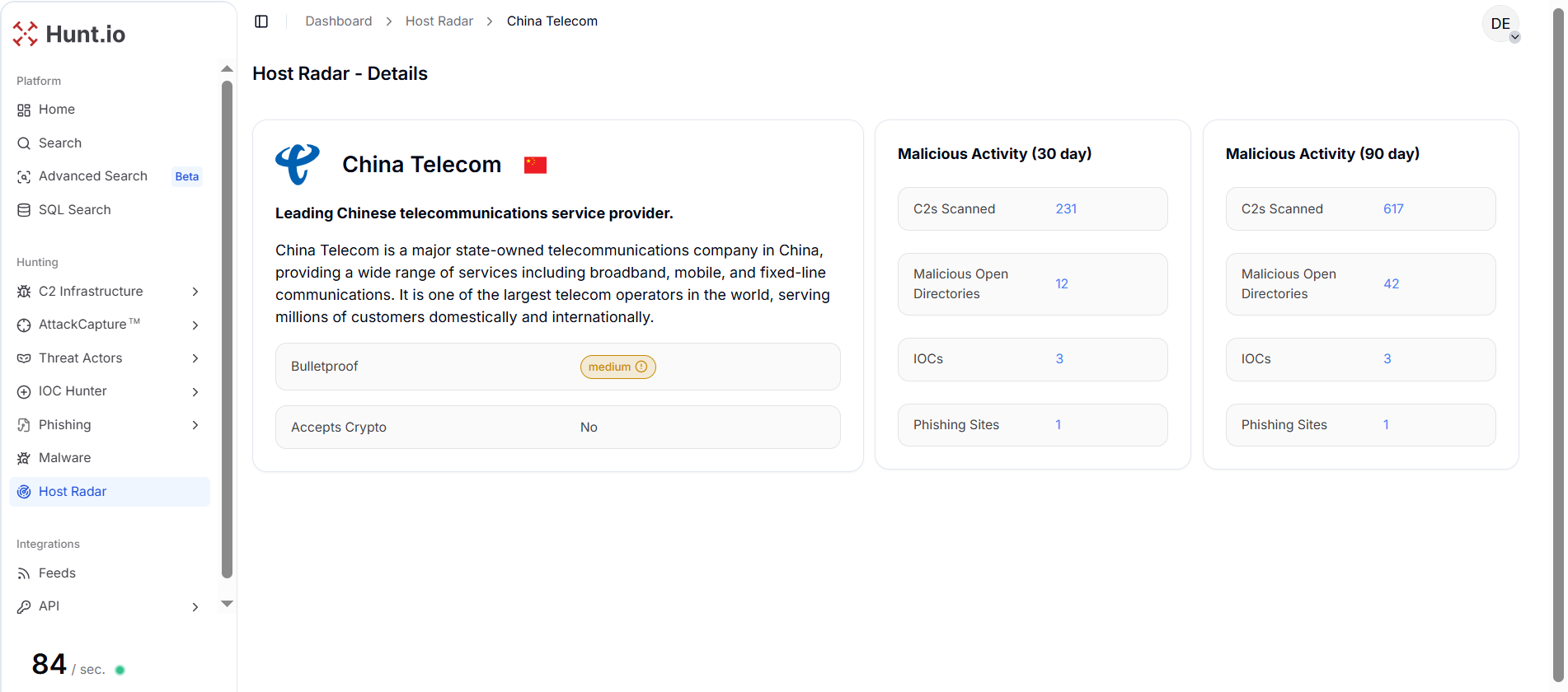

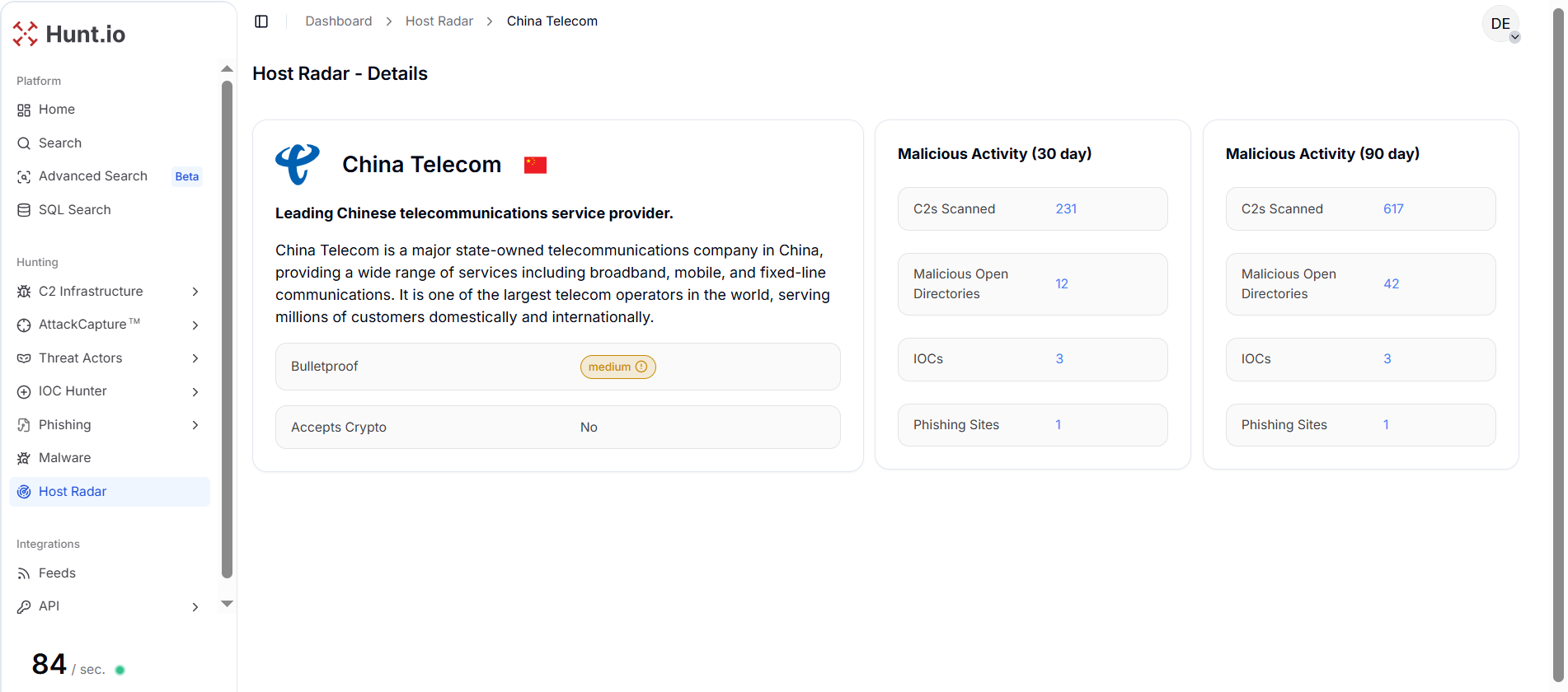

Figure 4. Tencent - Host Radar Detailed View: Detailed Host Radar view showing Tencent's diverse malicious footprint across C2 servers, phishing sites, open directories, and IOCs.In contrast, China Telecom shows moderate C2 activity with 617 servers and 42 open directories over the same period, reflecting targeted exploitation of its state-owned telecommunications infrastructure.

Figure 5. China Telecom - Host Radar Detailed View: Host Radar metrics for China Telecom reflecting moderate but persistent malicious infrastructure presence.

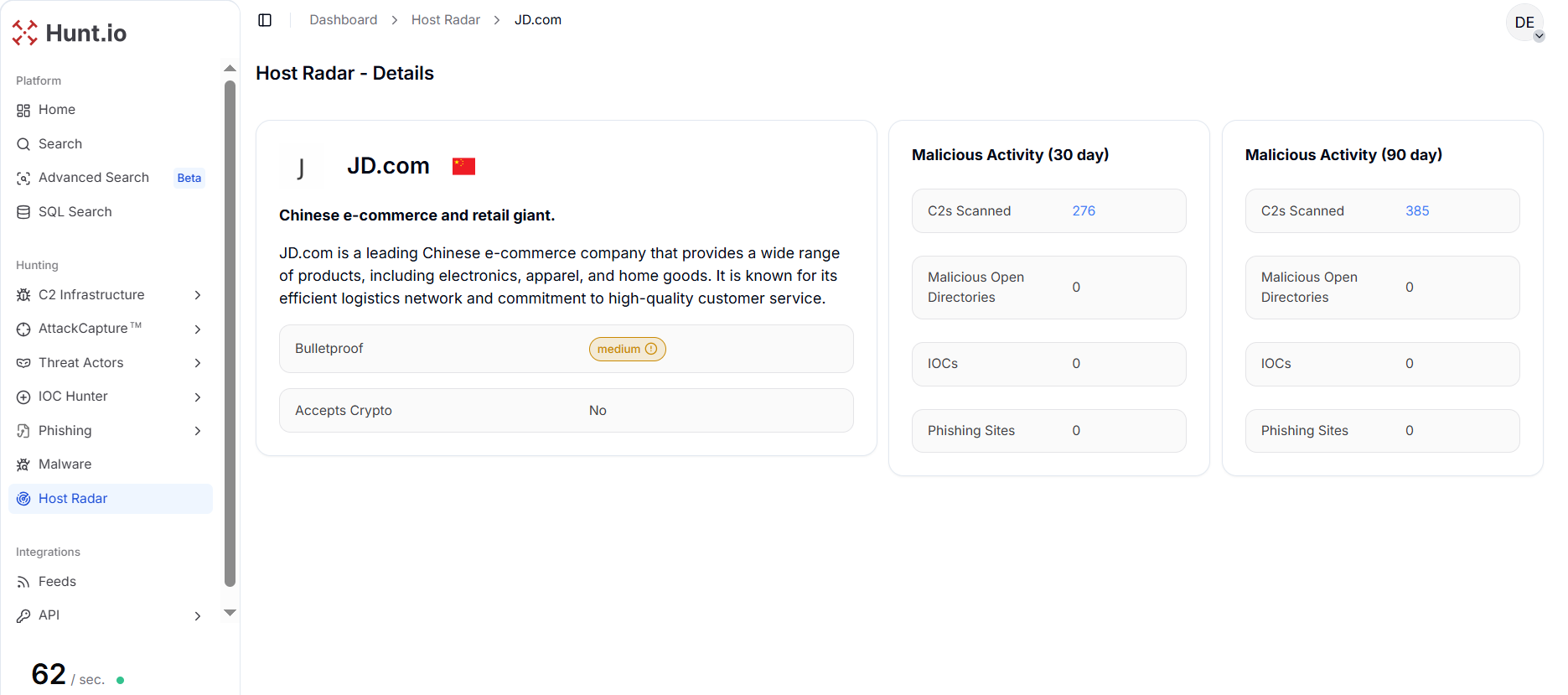

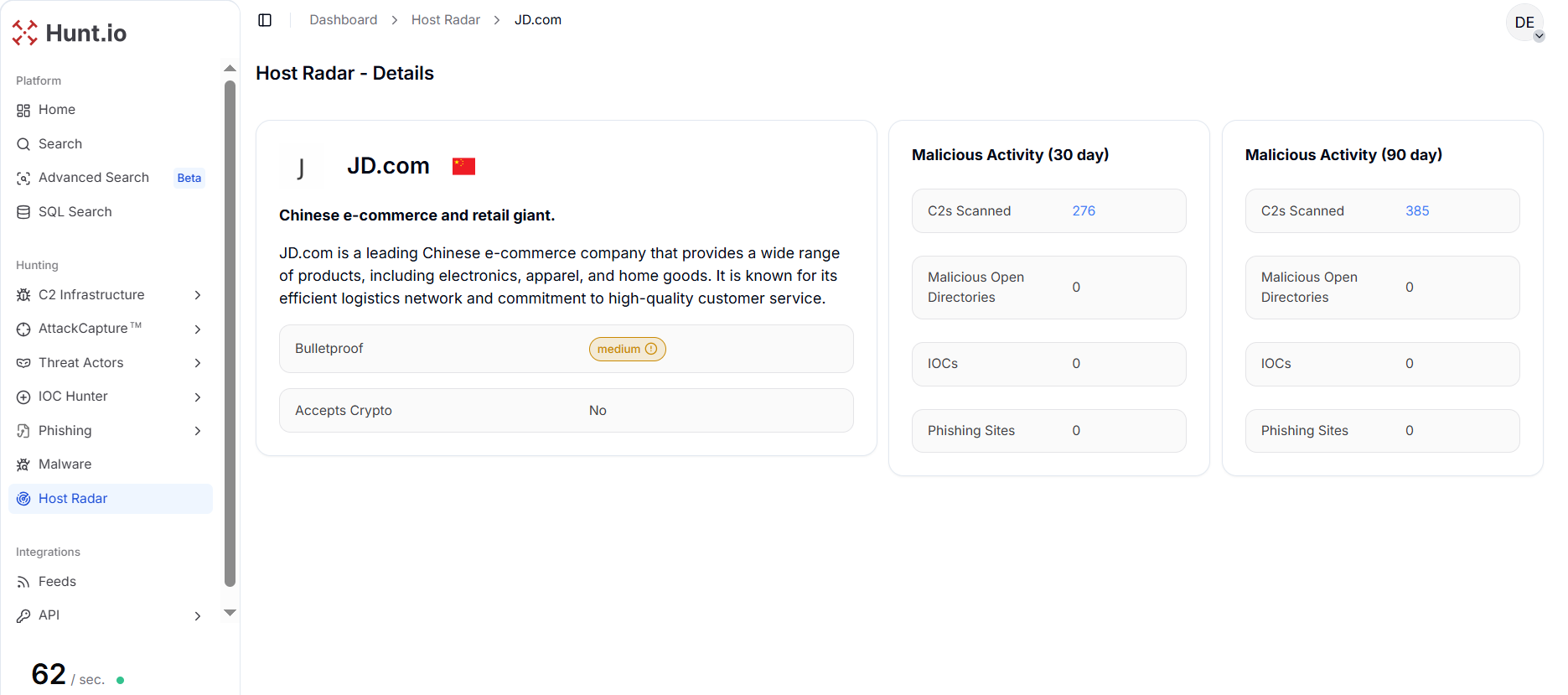

Figure 5. China Telecom - Host Radar Detailed View: Host Radar metrics for China Telecom reflecting moderate but persistent malicious infrastructure presence.JD.com, primarily an e-commerce provider, exhibits minimal malicious activity, with 385 C2 servers and no open directories, IOCs, or phishing sites, suggesting that retail networks are less attractive or less abused compared to large telecom and cloud platforms.

This suggests that retail and e-commerce platforms are less consistently abused for malware operations compared to telecom and cloud infrastructure.

Figure 6. JD.com - Host Radar Detailed View: Host Radar summary for JD.com showing comparatively limited malicious activity relative to telecom and cloud providers.

Figure 6. JD.com - Host Radar Detailed View: Host Radar summary for JD.com showing comparatively limited malicious activity relative to telecom and cloud providers.This data shows a clear view of which Chinese ISPs and cloud providers host the most malicious activity, helping prioritize monitoring and mitigation.

Viewed together, these provider-level results reveal a broader infrastructure pattern that becomes clearer when analyzed across all Chinese ISPs.

C2 Infrastructure Across Chinese ISPs

This section describes how Host Radar was used to detect and attribute more than 18,000 C2 servers operating within Chinese hosting environments over a three-month window.

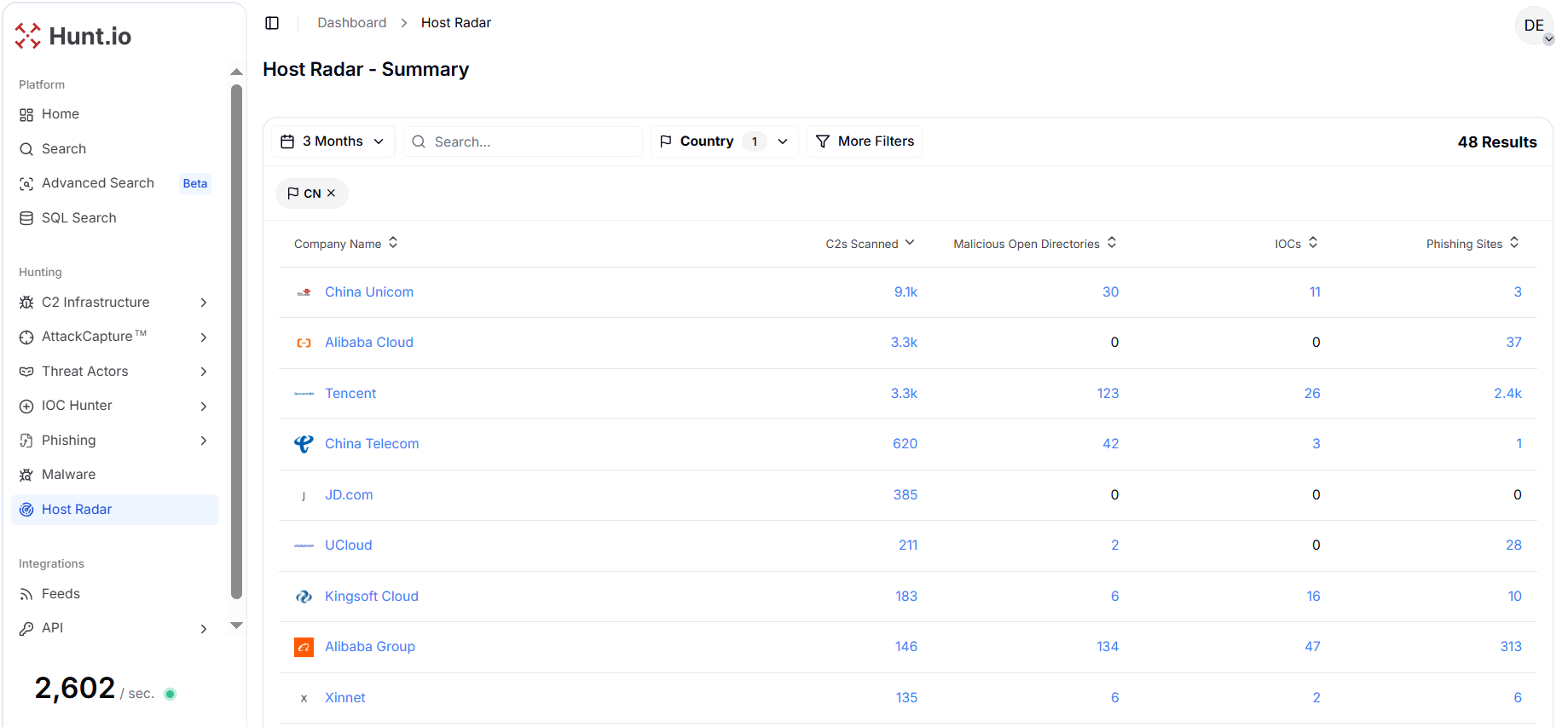

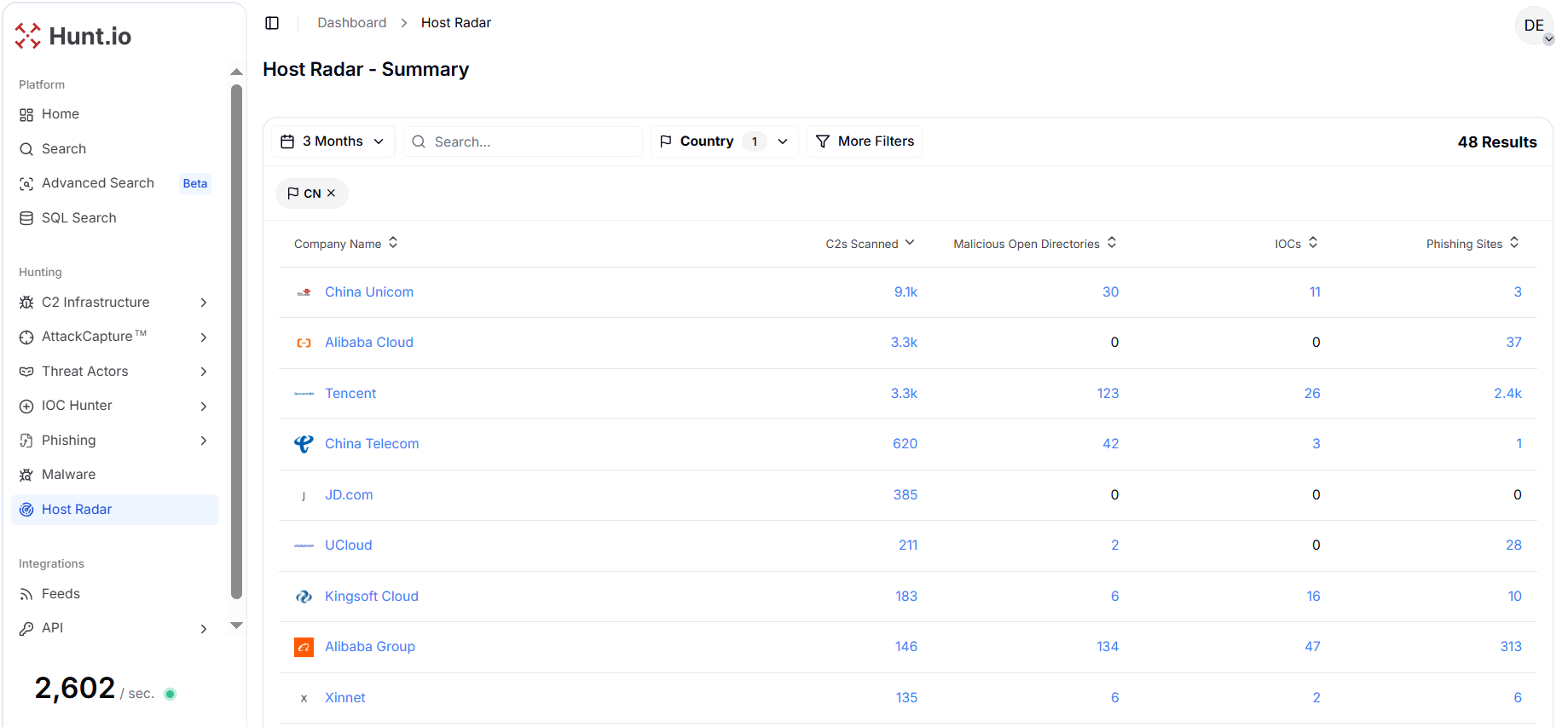

After applying the China country filter and restricting the observation window to the last three months, the Host Radar summary view reveals 48 distinct infrastructure providers and network entities operating within Chinese ISPs and cloud ecosystems that were associated with malicious activity.

This concentration supports infrastructure-level detection that remains effective despite IP churn.

Figure 7. Host Radar summary view showing malicious infrastructure detected across 48 Chinese ISPs and cloud providers over a three-month analysis window.

Figure 7. Host Radar summary view showing malicious infrastructure detected across 48 Chinese ISPs and cloud providers over a three-month analysis window.Dataset Scope and Observed Infrastructure Landscape Over China

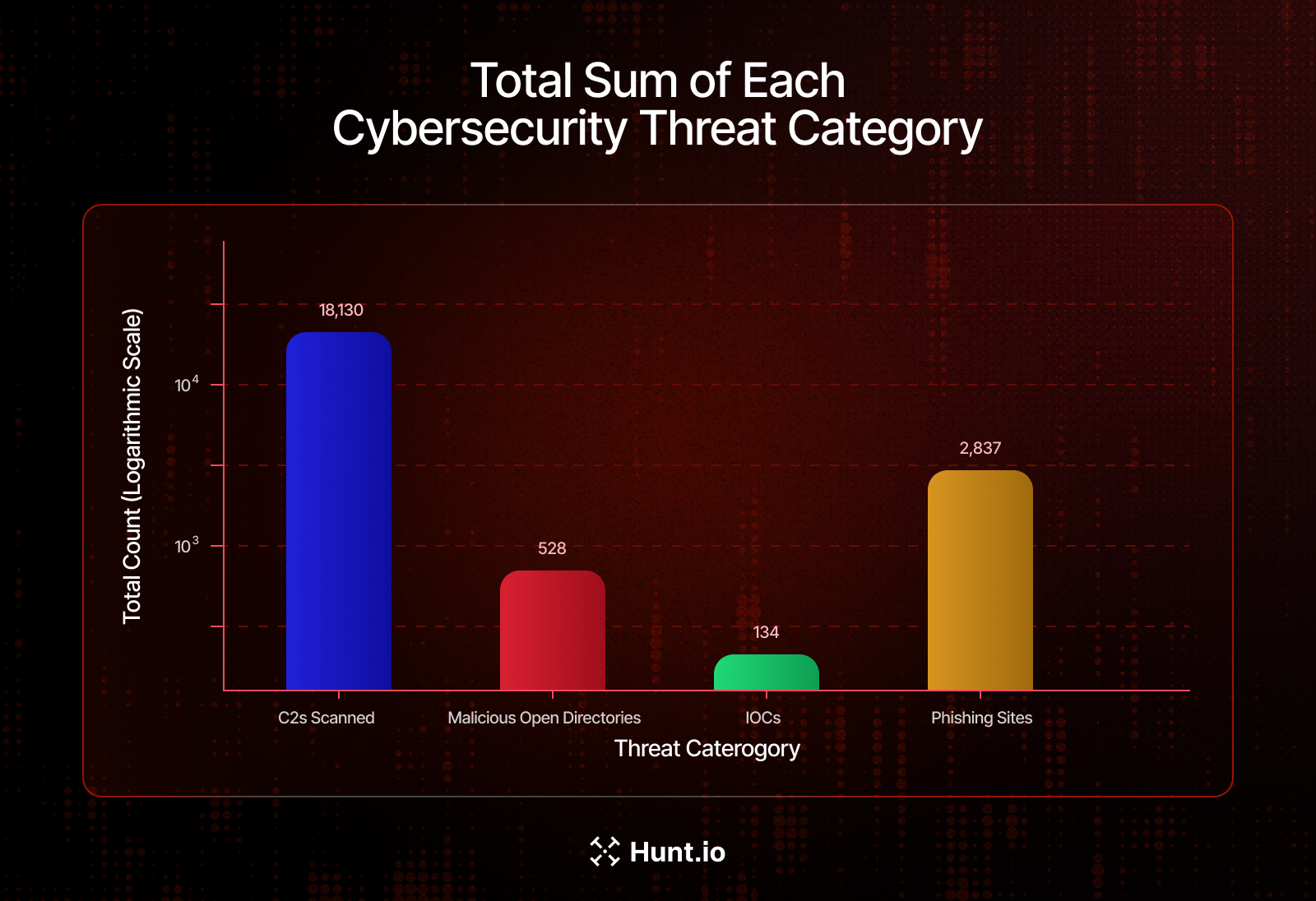

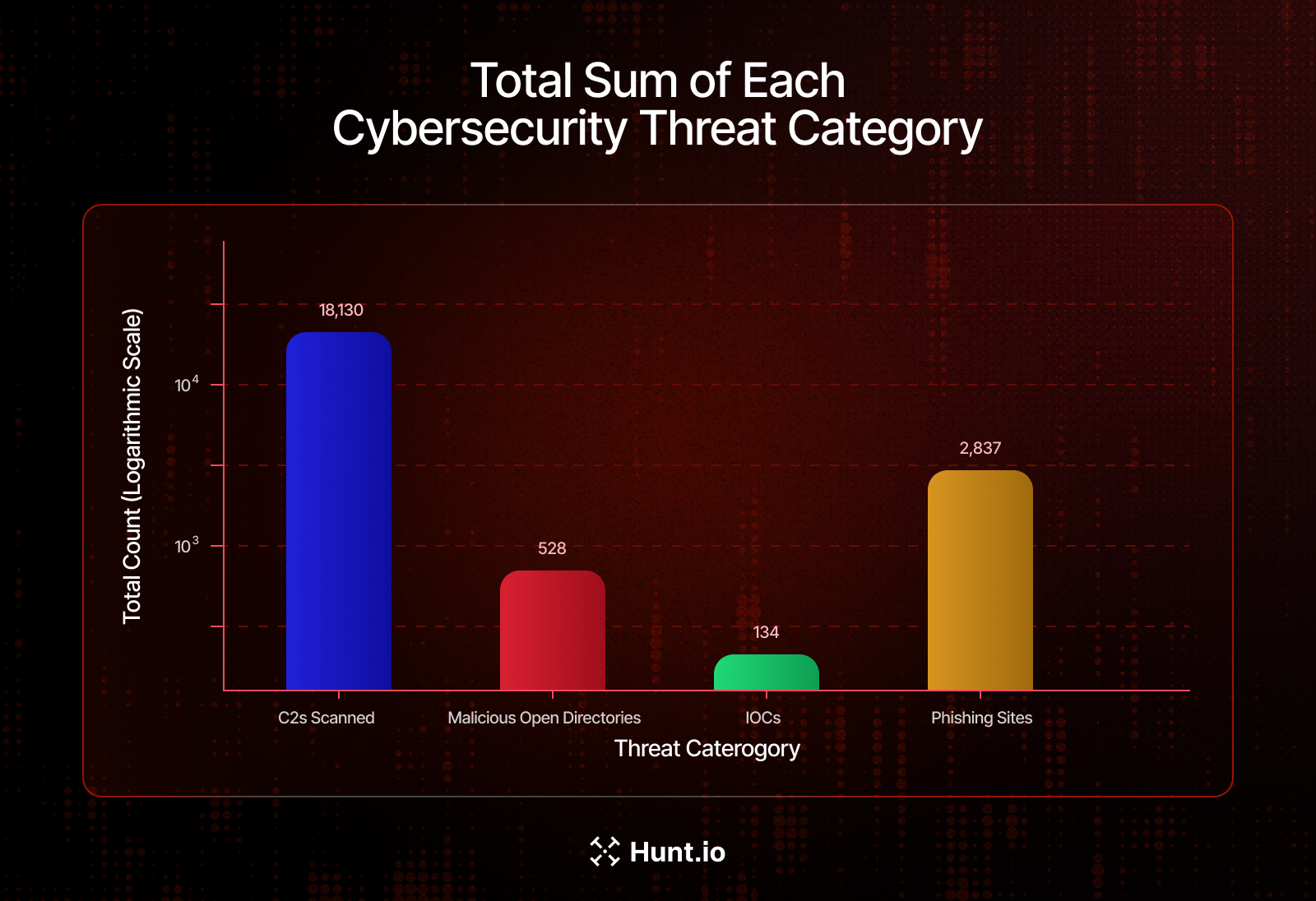

Across the full set of 48 Chinese infrastructure providers, Host Radar recorded a total of 21,629 malicious artifacts over the three-month observation period. This includes 18,000+ command-and-control (C2) servers, 528 malicious open directories, 134 indicators of compromise (IOCs) in Public Research, and 2,837 phishing sites.

The data reveals that C2 infrastructure dominates observed malicious activity at ~84% of all observed malicious artifacts, followed by phishing infrastructure at ~13%, while malicious open directories and public IOCs together contribute less than 4% of observed activity.

Figure 8. Aggregate breakdown of C2 servers (18,130), phishing sites (2,837), malicious open directories (528), and public IOCs (134) detected within Chinese hosting environments.

Figure 8. Aggregate breakdown of C2 servers (18,130), phishing sites (2,837), malicious open directories (528), and public IOCs (134) detected within Chinese hosting environments.Moreover, the bar graph below visualizes the Top 10 companies by C2 server detections, where China Unicom emerges as the most significant contributor with 9,100 detected C2 servers, accounting for nearly half of all observed C2 activity in this dataset.

This is followed by Alibaba Cloud and Tencent, each with approximately 3,300 C2 detections, indicating heavy abuse of large-scale cloud environments that offer rapid provisioning and high availability. China Telecom ranks fourth with 620 detections, while JD.com completes the top five with 385 C2 servers.

%402x.png) Figure 9. Top 10 Chinese infrastructure providers by number of detected C2 servers over a three-month window, highlighting concentration of malicious C2 activity within major telecom and cloud platforms.

Figure 9. Top 10 Chinese infrastructure providers by number of detected C2 servers over a three-month window, highlighting concentration of malicious C2 activity within major telecom and cloud platforms.Malware Family Distribution Within Chinese Networks

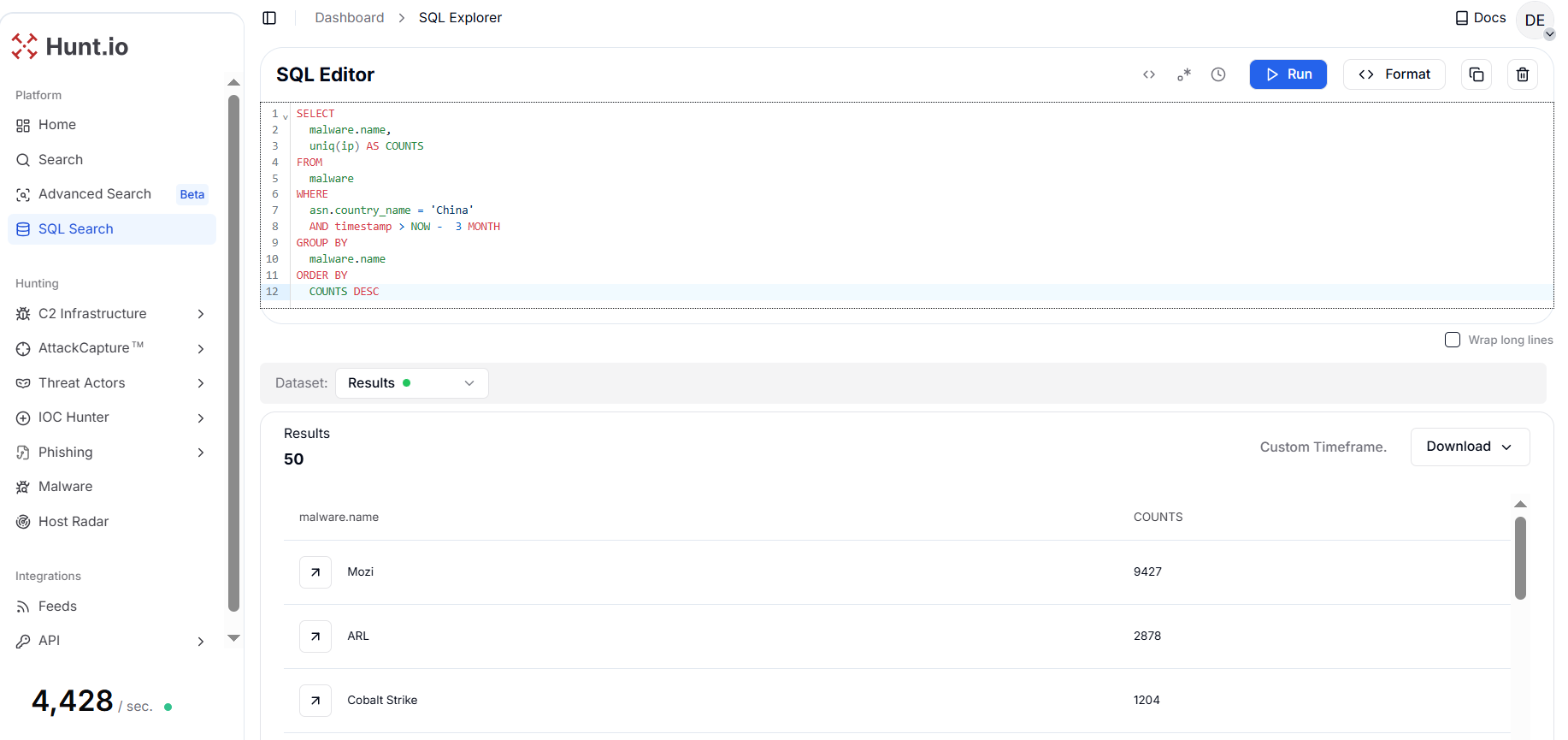

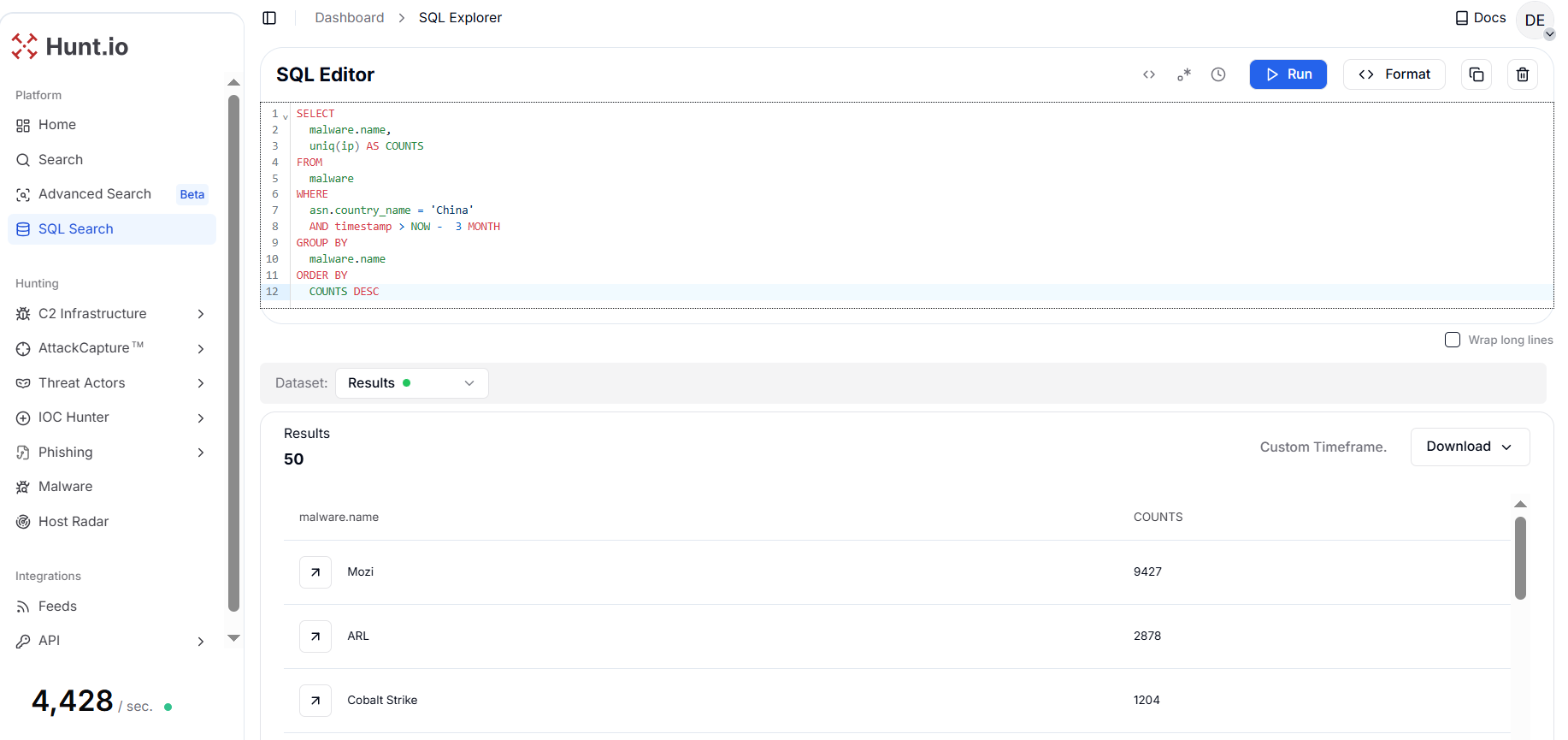

Using HuntSQL, we analyzed the distribution of command-and-control (C2) infrastructure across malware families hosted within Chinese networks over three months.

SELECT

malware.name,

uniq(ip) AS COUNTS

FROM

malware

WHERE

asn.country_name = 'China'

AND timestamp > NOW - 3 MONTH

GROUP BY

malware.name

ORDER BY

COUNTS DESC

CopyOutput Example:

Figure 10. HuntSQL query output showing the dominant malware families hosting C2 infrastructure within Chinese networks over three months.

Figure 10. HuntSQL query output showing the dominant malware families hosting C2 infrastructure within Chinese networks over three months.The results reveal that Mozi overwhelmingly leads with 9,427 unique C2 IPs, accounting for more than half of all observed C2 activity. The second largest cluster, ARL (2,878 C2s), suggests extensive use of red-team or post-exploitation frameworks being repurposed for malicious operations.

Mid-tier threats such as Cobalt Strike (1,204), Vshell (830), and Mirai (703) indicate persistent use of both commercial offensive frameworks and commodity botnets. Notably, Cobalt Strike (including unverified variants) appears twice in the top 10, reinforcing its role as a preferred C2 framework for advanced threat actors.

The presence of Gophish and Acunetix further shows that phishing operations and vulnerability scanning infrastructure are actively deployed as part of broader attack chains. Overall, the top 10 malware families alone account for the vast majority of detected C2 servers, confirming that C2 abuse in Chinese ISPs is concentrated, repeatable, and framework-driven rather than fragmented or opportunistic.

This concentration lets defenders focus on shared infrastructure rather than individual malware variants rather than chasing individual malware variants.

%402x.png) Figure 11. This bar graph illustrates the distribution of the Top 10 Malware Command and Control (C2) Families observed in China over the last three months.

Figure 11. This bar graph illustrates the distribution of the Top 10 Malware Command and Control (C2) Families observed in China over the last three months.Infrastructure Providers Hosting the Widest Malware Diversity

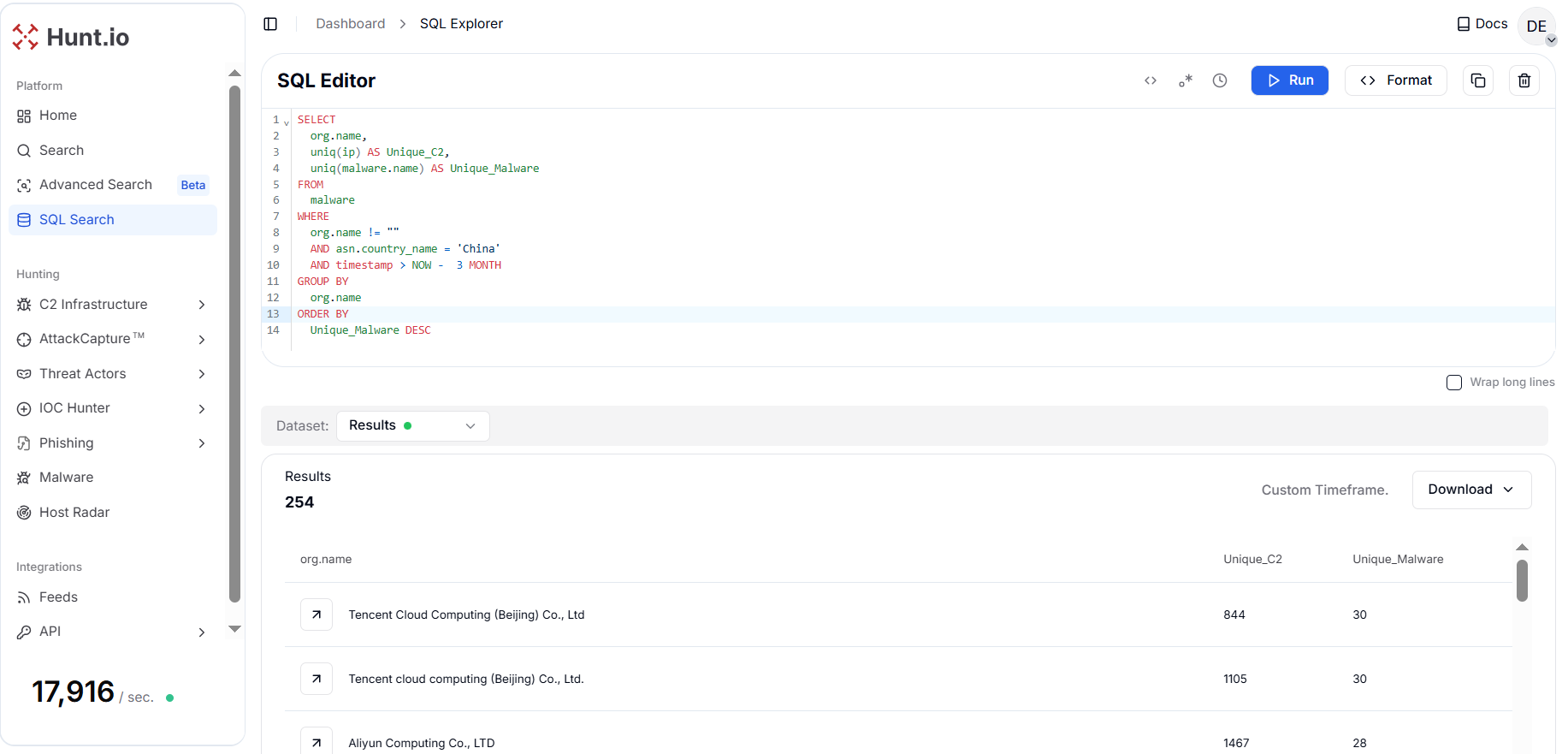

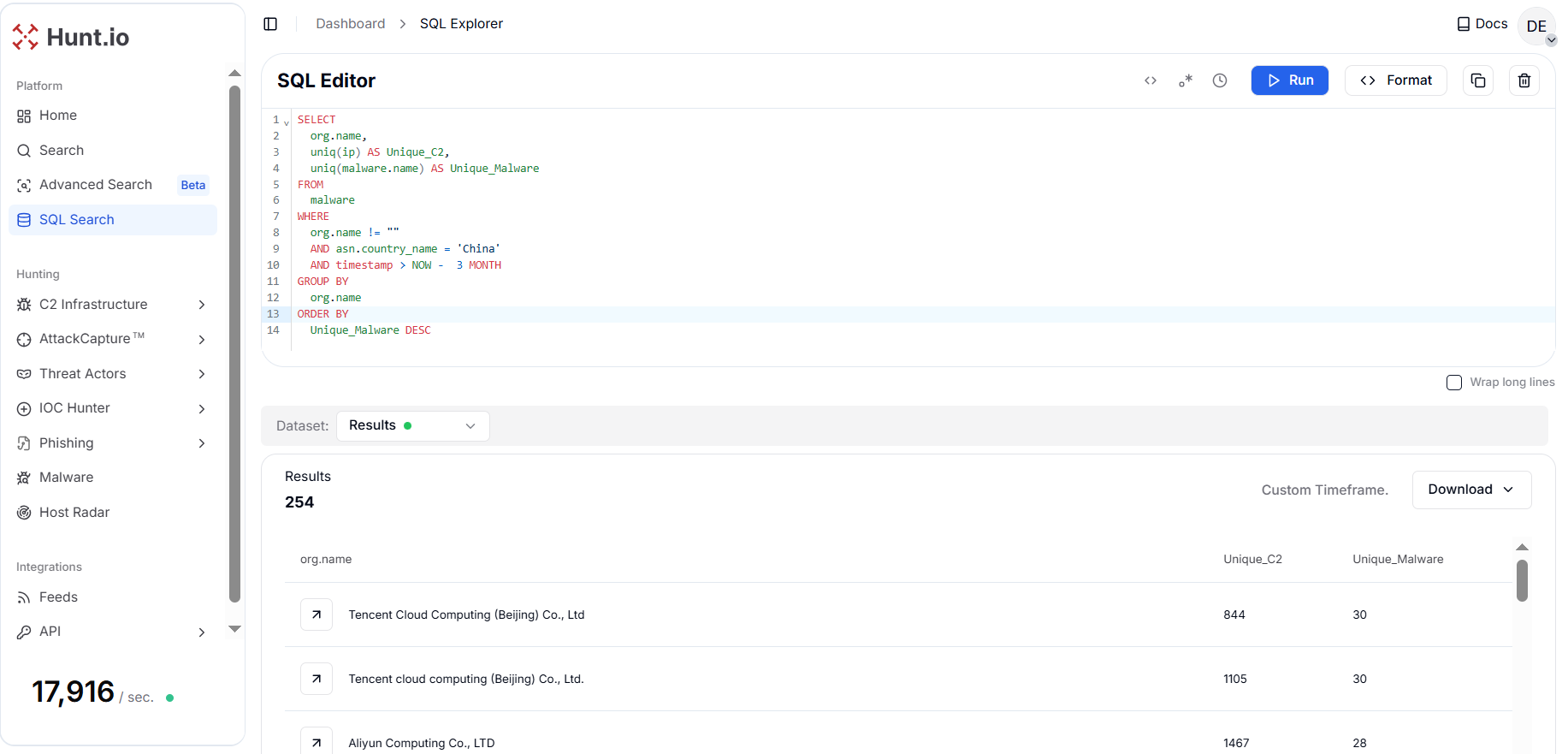

Additionally, another HuntSQL query is designed to surface organizations hosting the widest variety of malware activity in China in the last three months. It aggregates telemetry by org.name and calculates the number of distinct C2 IPs attributed to an organization, and Unique_Malware, which shows the diversity of malware families observed within that infrastructure.

SELECT

org.name,

uniq(ip) AS Unique_C2,

uniq(malware.name) AS Unique_Malware

FROM

malware

WHERE

org.name != ""

AND asn.country_name = 'China'

AND timestamp > NOW - 3 MONTH

GROUP BY

org.name

ORDER BY

Unique_Malware DESC

CopyOutput Example:

Figure 12. A HuntSQL query aggregating malware telemetry by a Chinese organization to identify providers hosting the widest variety of malware families.

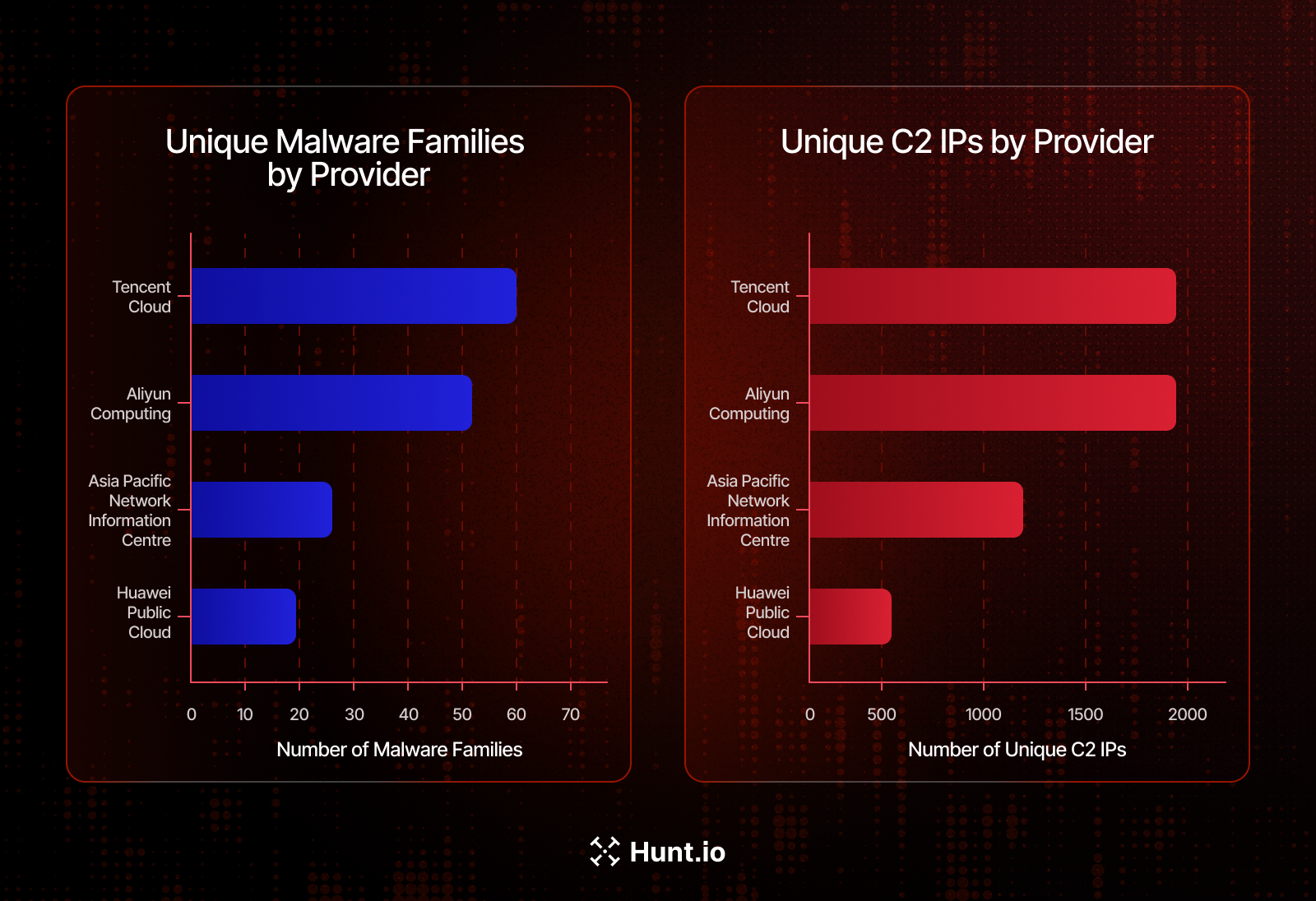

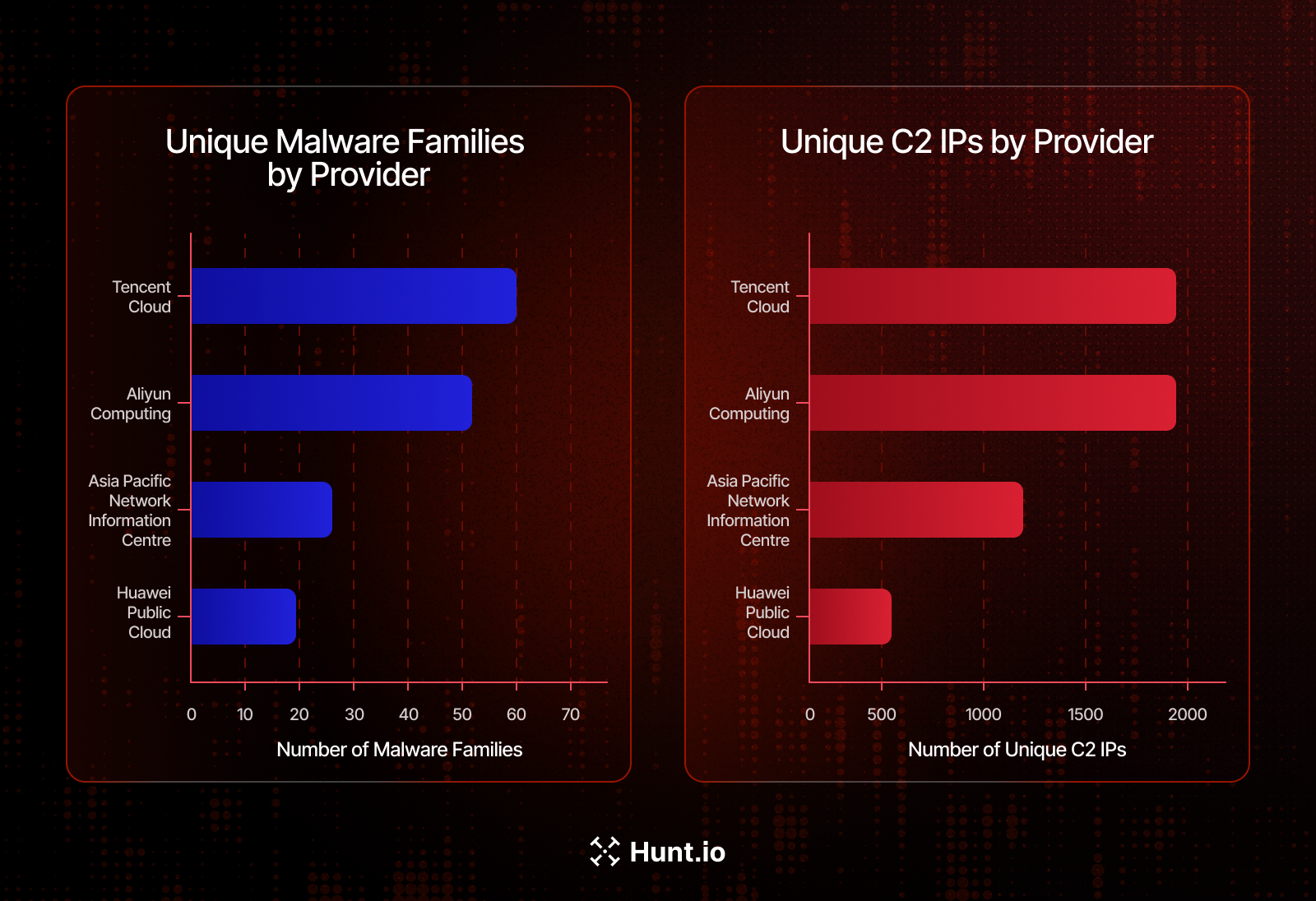

Figure 12. A HuntSQL query aggregating malware telemetry by a Chinese organization to identify providers hosting the widest variety of malware families.The results reveal a clear concentration of malware activity within a small set of major Asia-Pacific cloud and network providers. Providers hosting both high malware diversity and high C2 volume represent elevated systemic risk due to their repeated reuse across unrelated campaigns.

Tencent Cloud Computing (Beijing) Co., Ltd. leads the list, hosting 60 malware families and nearly 2,000 C2 endpoints, followed closely by Aliyun Computing Co., LTD with 52 malware families across approximately 1,956 C2 IPs.

Additional activity is observed within Asia Pacific Network Information Centre (APNIC), linked to 27 malware families, and Huawei Public Cloud Service, which accounts for 20 distinct families, underscoring how a few large providers are repeatedly leveraged by diverse threat actors.

Figure 13. Comparative analysis of malware infrastructure concentration by hosting provider. The left pane illustrates the diversity of malware families, while the right pane shows the total volume of unique Command-and-Control (C2) endpoints, highlighting Tencent

Figure 13. Comparative analysis of malware infrastructure concentration by hosting provider. The left pane illustrates the diversity of malware families, while the right pane shows the total volume of unique Command-and-Control (C2) endpoints, highlighting TencentMalicious Campaigns Observed Across Chinese Hosting Environments

The following real-world examples illustrate how the infrastructure patterns identified above translate into active malware campaigns, exploitation activity, and state-linked operations.

Over the same three-month period, Hunt.io tracking has surfaced multiple malicious command-and-control (C2) endpoints associated with commodity RATs and legacy malware families, beginning with NanoCore infrastructure hosted on Wowrack.com. Cobalt Strike campaigns were identified on Starry Network Limited, where an IP 45.155.220[.]44 appeared in a Weekly Threat Infrastructure Investigation, showing its role in broader threat ecosystem mapping rather than a single malware family.

Hunt.io further correlated AsyncRAT activity with Hubei Feixun Network Co., Ltd, where the endpoint 160.202.245[.]232 was flagged via threatfox.abuse.ch. Additional suspicious infrastructure (vshell) surfaced on Beijing Volcano Engine Technology Co., Ltd, where the IP 115.190.200[.]230 appeared in VirusTotal-indexed telemetry.

Phishing-driven malware delivery was observed on Beijing Baidu Netcom Science and Technology Co., Ltd, where 45.113.192[.]102 was tied to an Indian income-tax themed phishing campaign delivering NSecRTS.exe. Botnet and OT-focused threats were identified on ZhouyiSat Communications, including Mirai botnet activity at 185.245.35[.]68 and router-targeted attacks at 23.177.185[.]39. These detections align with known Mirai tradecraft and OT exploitation campaigns targeting exposed networking devices, reinforcing the role of smaller providers in supporting botnet command nodes.

The exploitation of the React2Shell vulnerability featured heavily across multiple providers. On XNNET LLC, one endpoint 43.247.134[.]215 was associated with React2Shell exploitation chains delivering XMRig cryptominers and Cobalt Strike, reflecting post-exploitation monetization and red-team framework abuse on compromised servers. Moreover, Hunt.io also identified suspicious activity on Huawei Cloud Service data centers, including infrastructure at 123.60.143[.]74 and 124.70.52[.]134, the latter linked to L3MON RAT.

The academic and research infrastructure was not immune. The China Education and Research Network Center (CERNET) hosted RondoDox botnet activity at 202.120.234[.]124 and 202.120.234[.]163, both linked to React2Shell exploitation campaigns. This shows how attackers take advantage of high-bandwidth academic networks once exposed services are compromised.

Advanced post-exploitation tooling was detected on China Telecom Beijing Tianjin Hebei Big Data Industry Park Branch, where 117.72.242[.]9 hosted a Cobalt Strike Beacon, indicating likely use as part of lateral-movement or long-term access operations rather than initial compromise. Similarly, an APT-linked activity was also observed on two IPs 106.126.3[.]56 and 106.126.3[.]78 hosted on infrastructure attributed to Quanzhou were tied to the BRONZE HIGHLAND (Evasive Panda) campaign deploying MgBot, confirming the presence of state-aligned threat activity within the broader Chinese hosting ecosystem.

A particularly high-impact case involved the DarkSpectre campaign, where infrastructure on China Unicom China169 Backbone at 58.144.143[.]27 supported malicious browser extension activity associated with millions of infections worldwide, illustrating how backbone-level infrastructure can be leveraged for global-scale abuse.

Tencent-operated infrastructure emerged as one of the most heavily abused environments. A phishing campaign in India targeting vehicle owners through SMS messages that threaten legal action for unpaid e-challans was hosted at 101.33.78[.]145 and 43.130.12[.]41.

The Gold Eye Dog (APT-Q-27) group is leveraging AWS S3 buckets to deliver sophisticated, certificate-signed backdoors that employ extensive anti-evasion checks and persistent remote-control capabilities. This campaign (43.154.170[.]196) marks an evolution of their toolset, using legitimate cloud infrastructure to deploy payloads capable of keylogging, screen capture, and full system command execution.

Researchers have identified active exploitation of a zero-day vulnerability in Gogs (CVE-2025-8110) that allows authenticated users to achieve Remote Code Execution (RCE) by bypassing symlink protections. An automated campaign has already compromised approximately 50% of exposed instances, deploying the Supershell C2 (106.53.108[.]81) payload for persistent reverse SSH access.

Another targeted phishing infrastructure associated with the Silver Fox campaign was hosted on Alibaba (US) Technology Co., Ltd. The group has shifted its focus toward Indian organizations, utilizing highly convincing Income Tax-themed lures to deploy the modular Valley RAT. This campaign is notable for its sophisticated multi-stage execution and successful evasion of traditional security perimeters.

The data shows that Chinese hosting providers and global clouds are used for both state-linked espionage and automated cybercrime, as APT groups like Silver Fox and Gold Eye Dog operate alongside commodity malware actors, creating a stealthy, professionalized threat ecosystem.

Infrastructure Observables

This research is based on a large set of infrastructure-level observables, including IP addresses, domains, and command-and-control endpoints that Hunt.io has identified and labeled as malicious infrastructure, active malware command-and-control, phishing infrastructure, or related abuse across Chinese ISPs and cloud providers.

Given the scale of the dataset, with more than 18,000 active C2 endpoints observed over a three-month period, publishing a static list here would offer limited practical value. Teams interested in accessing this data with proper context, attribution, and historical tracking can reach out to discuss research or operational access.

Conclusion

This analysis shows how a host-centric view changes how large-scale infrastructure abuse is understood and prioritized. Rather than chasing individual indicators that quickly expire, mapping malicious activity back to hosting providers, ISPs, and cloud platforms reveals where attacker infrastructure consistently concentrates and how it is reused across campaigns.

Across Chinese hosting environments, a small number of large telecom and cloud providers account for the majority of observed command-and-control activity, supporting everything from commodity malware and IoT botnets to phishing operations and state-linked tooling. By correlating C2 infrastructure, malware families, and publicly reported campaigns at scale, these patterns become visible despite IP churn and short-lived artifacts.

For security teams, this approach enables more resilient detection, faster prioritization, and infrastructure-level disruption strategies that are difficult for adversaries to evade. Host Radar and HuntSQL make this type of analysis practical by combining large-scale telemetry with flexible, analyst-driven investigation workflows.

If you want to explore this host-centric view of malicious infrastructure firsthand, you can see how Host Radar works in practice by booking a demo here: https://hunt.io/demo

Threat hunting often begins with a single indicator, such as a suspicious IP address, a beaconing domain, or a known malware family. Looking at those indicators individually makes the underlying infrastructure easy to miss.

While analyzing malicious activity across Chinese hosting environments, we repeatedly observed the same networks and providers appearing across unrelated campaigns. Commodity malware, phishing operations, and state-linked tooling were often hosted side by side within the same infrastructure, even as individual IPs and domains changed.

This pattern exposes the limits of indicator-driven hunting. In this article, we examine how malicious infrastructure clusters and persists across Chinese ISPs when viewed at country scale, and why a host-centric approach makes these relationships visible.

Key Takeaways

Analysis of recent telemetry surfaced more than 18,000 active C2 servers distributed across 48 Chinese infrastructure providers.

C2 infrastructure dominates malicious activity (~84%), far exceeding phishing infrastructure (~13%), with open directories and public IOCs together contributing less than 4%.

China Unicom alone hosts nearly half of all observed C2 servers, with Alibaba Cloud and Tencent following, highlighting heavy concentration in large, high-capacity networks.

Tencent and Alibaba Cloud exhibit high phishing activity alongside C2 hosting, reflecting attacker preference for scalable, trusted cloud platforms.

A small set of malware families (Mozi, ARL, Cobalt Strike, Mirai, Vshell) accounts for most C2 activity, showing framework-driven, repeatable abuse.

IoT-based botnet infrastructure remains deeply entrenched, with Mozi's dominance reinforcing China's role in large-scale IoT C2 operations.

Chinese infrastructure supports both cybercrime and APT activity, with RATs, cryptominers, phishing frameworks, and state-linked malware coexisting in the same environments.

High-trust networks are actively abused, as China169 Backbone, CHINANET, and CERNET demonstrate exploitation of telecom and academic infrastructure.

How We Analyze Malicious Infrastructure at Country Scale

Host Radar was built to analyze infrastructure-level abuse at country and ISP scale by correlating command-and-control servers, phishing infrastructure, malicious open directories, and public IOCs back to the hosting providers and network operators where they reside.

Rather than treating each artifact as an isolated signal, Host Radar brings these datasets together into a single view. This makes it possible to see where malicious infrastructure consistently clusters, how it shifts over time, and which providers repeatedly support unrelated campaigns.

At this level, long-running abuse patterns become visible even when individual IP addresses or domains rotate frequently.

Host Radar Data Aggregation Model

To support this type of analysis, Host Radar operates as a centralized aggregation layer for malicious infrastructure telemetry. Signals from C2 detection, phishing identification, open directory scanning, and IOC extraction are combined and enriched with hosting, ASN, and network ownership context.

As illustrated in Figure 1, this unified view allows analysts to pivot across providers, networks, and time windows without relying on individual IP- or domain-level indicators, making country-scale infrastructure analysis practical and repeatable.

Figure 1. Host Radar functions as a central intelligence layer by aggregating C2 activity, malicious open directories, phishing pages, and IOCs, mapping them to hosting providers and ISPs.

Figure 1. Host Radar functions as a central intelligence layer by aggregating C2 activity, malicious open directories, phishing pages, and IOCs, mapping them to hosting providers and ISPs.With this aggregation in place, we can examine how malicious infrastructure is distributed across individual Chinese providers.

China’s Malicious Infrastructure Landscape by Provider

The Host Radar summary for the top five Chinese infrastructure providers shows both the volume and range of malicious activity observed across these organizations over the last three months.

China Unicom, one of the largest telecommunications providers in China, exhibits the highest number of C2 servers, with 9,000 detected over 90 days, alongside 30 malicious open directories and 11 IOCs.

This single provider accounts for nearly half of all C2 infrastructure observed across Chinese hosting environments during the analysis period.

Figure 2. China Unicom - Host Radar Detailed View: Per-provider Host Radar breakdown for China Unicom, highlighting high-volume C2 activity and associated malicious artifacts.

Figure 2. China Unicom - Host Radar Detailed View: Per-provider Host Radar breakdown for China Unicom, highlighting high-volume C2 activity and associated malicious artifacts.Similarly, Alibaba Cloud, a leading cloud service provider, shows significant C2 presence with 3,300 servers and 37 phishing sites, although it has zero open directories or IOCs, reflecting how cloud environments are leveraged primarily for resilient command-and-control operations rather than exposed artifacts.

This contrasts with telecom providers, where C2 infrastructure dominates but phishing and open directory exposure remain comparatively lower.

Figure 3. Alibaba Cloud - Host Radar Detailed View: Host Radar metrics for Alibaba Cloud, illustrating significant C2 usage and phishing activity within cloud-hosted environments.

Figure 3. Alibaba Cloud - Host Radar Detailed View: Host Radar metrics for Alibaba Cloud, illustrating significant C2 usage and phishing activity within cloud-hosted environments.Tencent, the major Chinese technology conglomerate, demonstrates a more diverse malicious footprint. Over 90 days, it hosted 3,300 C2 servers, 122 open directories, 26 IOCs, and 2,400 phishing sites, indicating heavy abuse of its broad array of internet-facing services, including social media, gaming, and e-commerce platforms.

This matches what we see across the broader dataset, where phishing activity is concentrated in a small number of large cloud providers.

Figure 4. Tencent - Host Radar Detailed View: Detailed Host Radar view showing Tencent's diverse malicious footprint across C2 servers, phishing sites, open directories, and IOCs.

Figure 4. Tencent - Host Radar Detailed View: Detailed Host Radar view showing Tencent's diverse malicious footprint across C2 servers, phishing sites, open directories, and IOCs.In contrast, China Telecom shows moderate C2 activity with 617 servers and 42 open directories over the same period, reflecting targeted exploitation of its state-owned telecommunications infrastructure.

Figure 5. China Telecom - Host Radar Detailed View: Host Radar metrics for China Telecom reflecting moderate but persistent malicious infrastructure presence.

Figure 5. China Telecom - Host Radar Detailed View: Host Radar metrics for China Telecom reflecting moderate but persistent malicious infrastructure presence.JD.com, primarily an e-commerce provider, exhibits minimal malicious activity, with 385 C2 servers and no open directories, IOCs, or phishing sites, suggesting that retail networks are less attractive or less abused compared to large telecom and cloud platforms.

This suggests that retail and e-commerce platforms are less consistently abused for malware operations compared to telecom and cloud infrastructure.

Figure 6. JD.com - Host Radar Detailed View: Host Radar summary for JD.com showing comparatively limited malicious activity relative to telecom and cloud providers.

Figure 6. JD.com - Host Radar Detailed View: Host Radar summary for JD.com showing comparatively limited malicious activity relative to telecom and cloud providers.This data shows a clear view of which Chinese ISPs and cloud providers host the most malicious activity, helping prioritize monitoring and mitigation.

Viewed together, these provider-level results reveal a broader infrastructure pattern that becomes clearer when analyzed across all Chinese ISPs.

C2 Infrastructure Across Chinese ISPs

This section describes how Host Radar was used to detect and attribute more than 18,000 C2 servers operating within Chinese hosting environments over a three-month window.

After applying the China country filter and restricting the observation window to the last three months, the Host Radar summary view reveals 48 distinct infrastructure providers and network entities operating within Chinese ISPs and cloud ecosystems that were associated with malicious activity.

This concentration supports infrastructure-level detection that remains effective despite IP churn.

Figure 7. Host Radar summary view showing malicious infrastructure detected across 48 Chinese ISPs and cloud providers over a three-month analysis window.

Figure 7. Host Radar summary view showing malicious infrastructure detected across 48 Chinese ISPs and cloud providers over a three-month analysis window.Dataset Scope and Observed Infrastructure Landscape Over China

Across the full set of 48 Chinese infrastructure providers, Host Radar recorded a total of 21,629 malicious artifacts over the three-month observation period. This includes 18,000+ command-and-control (C2) servers, 528 malicious open directories, 134 indicators of compromise (IOCs) in Public Research, and 2,837 phishing sites.

The data reveals that C2 infrastructure dominates observed malicious activity at ~84% of all observed malicious artifacts, followed by phishing infrastructure at ~13%, while malicious open directories and public IOCs together contribute less than 4% of observed activity.

Figure 8. Aggregate breakdown of C2 servers (18,130), phishing sites (2,837), malicious open directories (528), and public IOCs (134) detected within Chinese hosting environments.

Figure 8. Aggregate breakdown of C2 servers (18,130), phishing sites (2,837), malicious open directories (528), and public IOCs (134) detected within Chinese hosting environments.Moreover, the bar graph below visualizes the Top 10 companies by C2 server detections, where China Unicom emerges as the most significant contributor with 9,100 detected C2 servers, accounting for nearly half of all observed C2 activity in this dataset.

This is followed by Alibaba Cloud and Tencent, each with approximately 3,300 C2 detections, indicating heavy abuse of large-scale cloud environments that offer rapid provisioning and high availability. China Telecom ranks fourth with 620 detections, while JD.com completes the top five with 385 C2 servers.

%402x.png) Figure 9. Top 10 Chinese infrastructure providers by number of detected C2 servers over a three-month window, highlighting concentration of malicious C2 activity within major telecom and cloud platforms.

Figure 9. Top 10 Chinese infrastructure providers by number of detected C2 servers over a three-month window, highlighting concentration of malicious C2 activity within major telecom and cloud platforms.Malware Family Distribution Within Chinese Networks

Using HuntSQL, we analyzed the distribution of command-and-control (C2) infrastructure across malware families hosted within Chinese networks over three months.

SELECT

malware.name,

uniq(ip) AS COUNTS

FROM

malware

WHERE

asn.country_name = 'China'

AND timestamp > NOW - 3 MONTH

GROUP BY

malware.name

ORDER BY

COUNTS DESC

CopyOutput Example:

Figure 10. HuntSQL query output showing the dominant malware families hosting C2 infrastructure within Chinese networks over three months.

Figure 10. HuntSQL query output showing the dominant malware families hosting C2 infrastructure within Chinese networks over three months.The results reveal that Mozi overwhelmingly leads with 9,427 unique C2 IPs, accounting for more than half of all observed C2 activity. The second largest cluster, ARL (2,878 C2s), suggests extensive use of red-team or post-exploitation frameworks being repurposed for malicious operations.

Mid-tier threats such as Cobalt Strike (1,204), Vshell (830), and Mirai (703) indicate persistent use of both commercial offensive frameworks and commodity botnets. Notably, Cobalt Strike (including unverified variants) appears twice in the top 10, reinforcing its role as a preferred C2 framework for advanced threat actors.

The presence of Gophish and Acunetix further shows that phishing operations and vulnerability scanning infrastructure are actively deployed as part of broader attack chains. Overall, the top 10 malware families alone account for the vast majority of detected C2 servers, confirming that C2 abuse in Chinese ISPs is concentrated, repeatable, and framework-driven rather than fragmented or opportunistic.

This concentration lets defenders focus on shared infrastructure rather than individual malware variants rather than chasing individual malware variants.

%402x.png) Figure 11. This bar graph illustrates the distribution of the Top 10 Malware Command and Control (C2) Families observed in China over the last three months.

Figure 11. This bar graph illustrates the distribution of the Top 10 Malware Command and Control (C2) Families observed in China over the last three months.Infrastructure Providers Hosting the Widest Malware Diversity

Additionally, another HuntSQL query is designed to surface organizations hosting the widest variety of malware activity in China in the last three months. It aggregates telemetry by org.name and calculates the number of distinct C2 IPs attributed to an organization, and Unique_Malware, which shows the diversity of malware families observed within that infrastructure.

SELECT

org.name,

uniq(ip) AS Unique_C2,

uniq(malware.name) AS Unique_Malware

FROM

malware

WHERE

org.name != ""

AND asn.country_name = 'China'

AND timestamp > NOW - 3 MONTH

GROUP BY

org.name

ORDER BY

Unique_Malware DESC

CopyOutput Example:

Figure 12. A HuntSQL query aggregating malware telemetry by a Chinese organization to identify providers hosting the widest variety of malware families.

Figure 12. A HuntSQL query aggregating malware telemetry by a Chinese organization to identify providers hosting the widest variety of malware families.The results reveal a clear concentration of malware activity within a small set of major Asia-Pacific cloud and network providers. Providers hosting both high malware diversity and high C2 volume represent elevated systemic risk due to their repeated reuse across unrelated campaigns.

Tencent Cloud Computing (Beijing) Co., Ltd. leads the list, hosting 60 malware families and nearly 2,000 C2 endpoints, followed closely by Aliyun Computing Co., LTD with 52 malware families across approximately 1,956 C2 IPs.

Additional activity is observed within Asia Pacific Network Information Centre (APNIC), linked to 27 malware families, and Huawei Public Cloud Service, which accounts for 20 distinct families, underscoring how a few large providers are repeatedly leveraged by diverse threat actors.

Figure 13. Comparative analysis of malware infrastructure concentration by hosting provider. The left pane illustrates the diversity of malware families, while the right pane shows the total volume of unique Command-and-Control (C2) endpoints, highlighting Tencent

Figure 13. Comparative analysis of malware infrastructure concentration by hosting provider. The left pane illustrates the diversity of malware families, while the right pane shows the total volume of unique Command-and-Control (C2) endpoints, highlighting TencentMalicious Campaigns Observed Across Chinese Hosting Environments

The following real-world examples illustrate how the infrastructure patterns identified above translate into active malware campaigns, exploitation activity, and state-linked operations.

Over the same three-month period, Hunt.io tracking has surfaced multiple malicious command-and-control (C2) endpoints associated with commodity RATs and legacy malware families, beginning with NanoCore infrastructure hosted on Wowrack.com. Cobalt Strike campaigns were identified on Starry Network Limited, where an IP 45.155.220[.]44 appeared in a Weekly Threat Infrastructure Investigation, showing its role in broader threat ecosystem mapping rather than a single malware family.

Hunt.io further correlated AsyncRAT activity with Hubei Feixun Network Co., Ltd, where the endpoint 160.202.245[.]232 was flagged via threatfox.abuse.ch. Additional suspicious infrastructure (vshell) surfaced on Beijing Volcano Engine Technology Co., Ltd, where the IP 115.190.200[.]230 appeared in VirusTotal-indexed telemetry.

Phishing-driven malware delivery was observed on Beijing Baidu Netcom Science and Technology Co., Ltd, where 45.113.192[.]102 was tied to an Indian income-tax themed phishing campaign delivering NSecRTS.exe. Botnet and OT-focused threats were identified on ZhouyiSat Communications, including Mirai botnet activity at 185.245.35[.]68 and router-targeted attacks at 23.177.185[.]39. These detections align with known Mirai tradecraft and OT exploitation campaigns targeting exposed networking devices, reinforcing the role of smaller providers in supporting botnet command nodes.

The exploitation of the React2Shell vulnerability featured heavily across multiple providers. On XNNET LLC, one endpoint 43.247.134[.]215 was associated with React2Shell exploitation chains delivering XMRig cryptominers and Cobalt Strike, reflecting post-exploitation monetization and red-team framework abuse on compromised servers. Moreover, Hunt.io also identified suspicious activity on Huawei Cloud Service data centers, including infrastructure at 123.60.143[.]74 and 124.70.52[.]134, the latter linked to L3MON RAT.

The academic and research infrastructure was not immune. The China Education and Research Network Center (CERNET) hosted RondoDox botnet activity at 202.120.234[.]124 and 202.120.234[.]163, both linked to React2Shell exploitation campaigns. This shows how attackers take advantage of high-bandwidth academic networks once exposed services are compromised.

Advanced post-exploitation tooling was detected on China Telecom Beijing Tianjin Hebei Big Data Industry Park Branch, where 117.72.242[.]9 hosted a Cobalt Strike Beacon, indicating likely use as part of lateral-movement or long-term access operations rather than initial compromise. Similarly, an APT-linked activity was also observed on two IPs 106.126.3[.]56 and 106.126.3[.]78 hosted on infrastructure attributed to Quanzhou were tied to the BRONZE HIGHLAND (Evasive Panda) campaign deploying MgBot, confirming the presence of state-aligned threat activity within the broader Chinese hosting ecosystem.

A particularly high-impact case involved the DarkSpectre campaign, where infrastructure on China Unicom China169 Backbone at 58.144.143[.]27 supported malicious browser extension activity associated with millions of infections worldwide, illustrating how backbone-level infrastructure can be leveraged for global-scale abuse.

Tencent-operated infrastructure emerged as one of the most heavily abused environments. A phishing campaign in India targeting vehicle owners through SMS messages that threaten legal action for unpaid e-challans was hosted at 101.33.78[.]145 and 43.130.12[.]41.

The Gold Eye Dog (APT-Q-27) group is leveraging AWS S3 buckets to deliver sophisticated, certificate-signed backdoors that employ extensive anti-evasion checks and persistent remote-control capabilities. This campaign (43.154.170[.]196) marks an evolution of their toolset, using legitimate cloud infrastructure to deploy payloads capable of keylogging, screen capture, and full system command execution.

Researchers have identified active exploitation of a zero-day vulnerability in Gogs (CVE-2025-8110) that allows authenticated users to achieve Remote Code Execution (RCE) by bypassing symlink protections. An automated campaign has already compromised approximately 50% of exposed instances, deploying the Supershell C2 (106.53.108[.]81) payload for persistent reverse SSH access.

Another targeted phishing infrastructure associated with the Silver Fox campaign was hosted on Alibaba (US) Technology Co., Ltd. The group has shifted its focus toward Indian organizations, utilizing highly convincing Income Tax-themed lures to deploy the modular Valley RAT. This campaign is notable for its sophisticated multi-stage execution and successful evasion of traditional security perimeters.

The data shows that Chinese hosting providers and global clouds are used for both state-linked espionage and automated cybercrime, as APT groups like Silver Fox and Gold Eye Dog operate alongside commodity malware actors, creating a stealthy, professionalized threat ecosystem.

Infrastructure Observables

This research is based on a large set of infrastructure-level observables, including IP addresses, domains, and command-and-control endpoints that Hunt.io has identified and labeled as malicious infrastructure, active malware command-and-control, phishing infrastructure, or related abuse across Chinese ISPs and cloud providers.

Given the scale of the dataset, with more than 18,000 active C2 endpoints observed over a three-month period, publishing a static list here would offer limited practical value. Teams interested in accessing this data with proper context, attribution, and historical tracking can reach out to discuss research or operational access.

Conclusion

This analysis shows how a host-centric view changes how large-scale infrastructure abuse is understood and prioritized. Rather than chasing individual indicators that quickly expire, mapping malicious activity back to hosting providers, ISPs, and cloud platforms reveals where attacker infrastructure consistently concentrates and how it is reused across campaigns.

Across Chinese hosting environments, a small number of large telecom and cloud providers account for the majority of observed command-and-control activity, supporting everything from commodity malware and IoT botnets to phishing operations and state-linked tooling. By correlating C2 infrastructure, malware families, and publicly reported campaigns at scale, these patterns become visible despite IP churn and short-lived artifacts.

For security teams, this approach enables more resilient detection, faster prioritization, and infrastructure-level disruption strategies that are difficult for adversaries to evade. Host Radar and HuntSQL make this type of analysis practical by combining large-scale telemetry with flexible, analyst-driven investigation workflows.

If you want to explore this host-centric view of malicious infrastructure firsthand, you can see how Host Radar works in practice by booking a demo here: https://hunt.io/demo

Related Post

Related Post

Related Post

Threat Research

Jun 19, 2025

•

12

min read

Our threat hunters uncovered a PowerShell loader hosted by Chinese and Russian providers, linked to active Cobalt Strike infrastructure.

Read Article

Threat Research

Threat Research

Jun 19, 2025

•

12

min read

Our threat hunters uncovered a PowerShell loader hosted by Chinese and Russian providers, linked to active Cobalt Strike infrastructure.

Read Article

Threat Research

Threat Research

Jun 19, 2025

•

12

min read

Our threat hunters uncovered a PowerShell loader hosted by Chinese and Russian providers, linked to active Cobalt Strike infrastructure.

Read Article

Threat Research

Threat Research

May 8, 2024

•

7

min read

From initial access and privilege escalation to lateral movement and data collection, the open-source platform Viper...

Read Article

Threat Research

Threat Research

May 8, 2024

•

7

min read

From initial access and privilege escalation to lateral movement and data collection, the open-source platform Viper...

Read Article

Threat Research

Threat Research

May 8, 2024

•

7

min read

From initial access and privilege escalation to lateral movement and data collection, the open-source platform Viper...

Read Article

Threat Research

Threat Research

Dec 3, 2024

•

8

min read

Uncover the infrastructure and learn how a unique watermark led to the discovery of Cobalt Strike 4.10 team servers impersonating well-known brands.

Read Article

Threat Research

Threat Research

Dec 3, 2024

•

8

min read

Uncover the infrastructure and learn how a unique watermark led to the discovery of Cobalt Strike 4.10 team servers impersonating well-known brands.

Read Article

Threat Research

Threat Research

Dec 3, 2024

•

8

min read

Uncover the infrastructure and learn how a unique watermark led to the discovery of Cobalt Strike 4.10 team servers impersonating well-known brands.

Read Article

Threat Research

Find the threat

before it finds you

Hunt adversary infrastructure in real time. Surface C2 servers, enrich IOCs,

and map attacker activity at scale with our unified threat hunting platform.

Find the threat

before it finds you

Hunt adversary infrastructure in real time. Surface C2 servers, enrich IOCs,

and map attacker activity at scale with our unified threat hunting platform.

Find the threat

before it finds you

Hunt adversary infrastructure in real time. Surface C2 servers, enrich IOCs,

and map attacker activity at scale with our unified threat hunting platform.

©2025 Hunt Intelligence, Inc.