Gateway to Intrusion: Malware Delivery Via Open Directories

Gateway to Intrusion: Malware Delivery Via Open Directories

Published on

Oct 31, 2023

Attackers constantly devise new and sophisticated methods of delivering malware to infiltrate systems and exfiltrate data. For some actors, these threats lurk in dark corners of the internet, behind multiple proxies, or even utilizing previously compromised hosts to initiate attacks.

In other cases, these threats hide in plain sight, using open directories as a gateway to deliver malware to their victims.

Hunt constantly crawls the internet for open directories, downloading every file on the server, including scripts, which defenders can read (thanks to Hunt) without opening the file.

In this post, I'll provide two recent examples exploring how threat actors leverage open directories to deliver malware to computer systems.

AsyncRAT & BITS

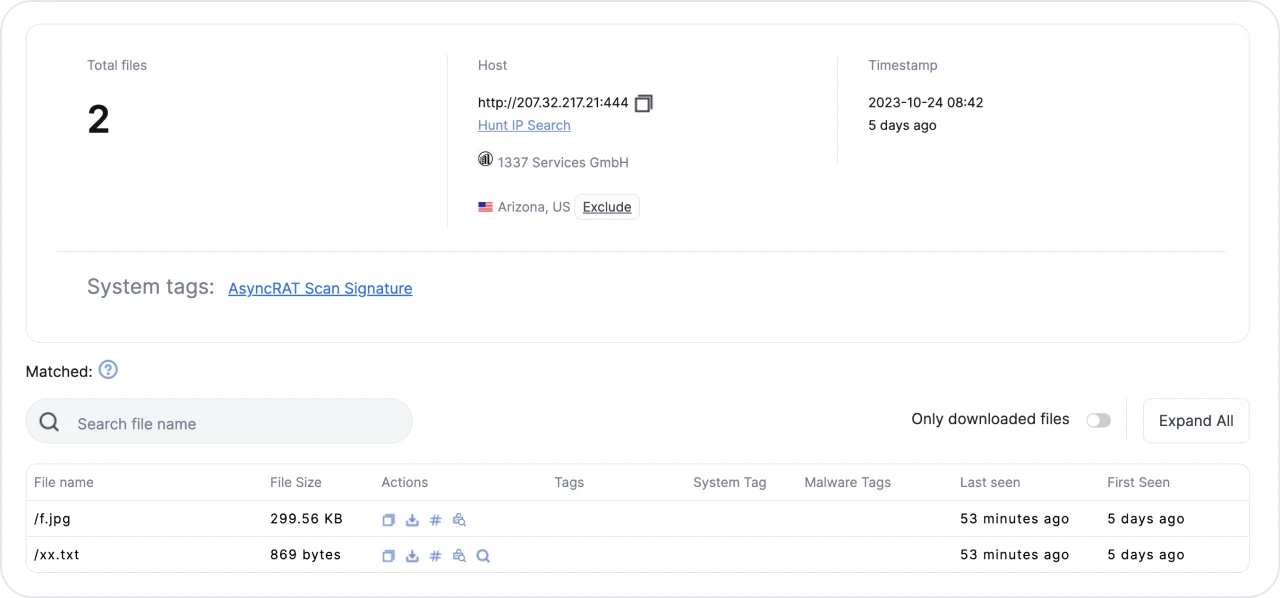

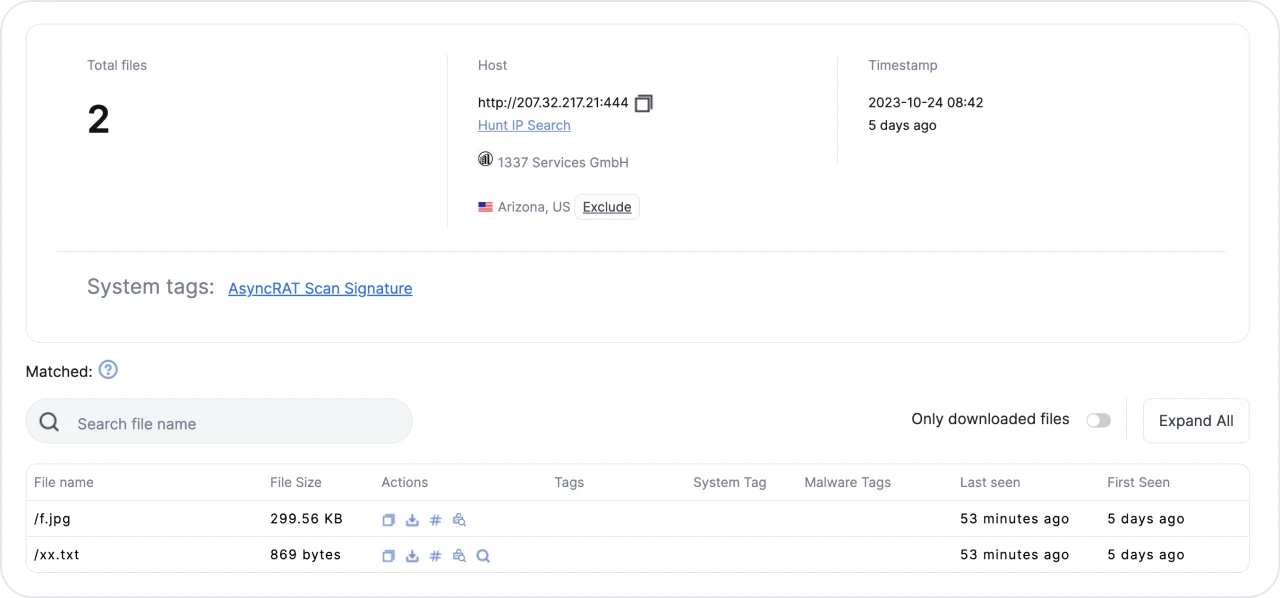

Recently, Hunt identified a malicious IP address serving AsyncRAT that hosted two files in an open directory.

Figure 1: Results of Hunt crawling the open directory at 207.32.217[.]21.

Figure 1: Results of Hunt crawling the open directory at 207.32.217[.]21.Little thought went into naming the files, which could have given us an idea of the actor's intent.

Clicking on the magnifying glass under the "Actions" tab will open a smaller window, allowing us to read the file.

Figure 2: Contents of xx.txt

Figure 2: Contents of xx.txtxx.txt contains VBScript, which does the following:

1 Creates an XML file containing a PowerShell command, saving the file to the system as "temp.xml."

2 Extracts the content within the "" section of the XML file and uses Microsoft BITS (Background Intelligent Transfer Service) to download the file "f.jpg" from the same server.

3 Remove all traces of "temp.xml" from the system using the FileSystemObject command

Naming a file "xx.txt" presumably indicates a placeholder, which the actor may rename uniquely for each campaign or target. Likely, delivery methods could include attaching the text file in a crafted email or as a series of files offered to the victim by other means.

Let's move to a VM and see what's behind f.jpg.

Figure 3: Detect it Easy results of f.jpg

Figure 3: Detect it Easy results of f.jpgf.jpg is a zip file containing 9 additional files. We'll keep digging from here, unzip the file, and see what we find.

Figure 4: Contents of f.jpg

Figure 4: Contents of f.jpgLet's wrap up this first example. If you are analyzing the files at home, let me know what you found.

Python Executable Wrapped in Fernet

The second case is a malicious IP Hunt detected as hosting a login page for Supershell, an open-source C2 platform, and two more files in an open directory.

Figure 5: Hunt results of open directory at 121.37.21[.]229

Figure 5: Hunt results of open directory at 121.37.21[.]229Once again, we have some rather dull file names. 1.exe is rather large at 10 MB, but let's look at a.txt.

Figure 6: Encoded/encrypted data of a.txt.

Figure 6: Encoded/encrypted data of a.txt.The text in the file is encoded or encrypted; we just don't know with what algorithm yet.

Even with a 10MB file, phishing remains a viable delivery method, in addition to hosting the file somewhere as a popular tool for download.

Moving back to our VM, let's look at 1. exe.

Figure 7: Detect it Easy results of 1.exe

Figure 7: Detect it Easy results of 1.exeLet's skip forward and cover the compiled Python files extracted from the executable.

Figure 8: Decompiled code of b.pyc and interesting string

Figure 8: Decompiled code of b.pyc and interesting string Figure 9: decrypted code from a.txt

Figure 9: decrypted code from a.txtFrom Figures 8 & 9, we can see that 1.exe:

Defines a key using the Fernet encryption scheme to decrypt "sectr" stored in "destr."

The inner function, "A" executes the "destr" value.

"T2" Base64 encodes a message in Chinese twice.

"T1" implements the QuickSort algorithm.

Function "00619654()" makes a GET request and downloads a.txt from the open directory, then tries to run the "06936762() function.

From Figures 8 & 9, we can see that 1.exe:

Note: I couldn't find the message in string "t2" used in other malicious code. If you've seen it used before, feel free to reach out on X (Twitter).

As we can see in Figure 9, the result of a.txt is a Python script that decrypts shellcode (encrypted with Fernet) in memory and executes it.

VirusTotal and Triage detect 1.exe and the shellcode as part of the Cobalt Strike penetration testing tool.

Conclusion

As we've explored, exposed directories serve as a common vector for malware delivery and the subsequent loading of additional malicious components. Often overlooked due to the plethora of malware found in directories, it is crucial that we, as defenders, remember that these servers can be the beginning of a bad day for our network.

For further hunting, here are more examples:

Attackers constantly devise new and sophisticated methods of delivering malware to infiltrate systems and exfiltrate data. For some actors, these threats lurk in dark corners of the internet, behind multiple proxies, or even utilizing previously compromised hosts to initiate attacks.

In other cases, these threats hide in plain sight, using open directories as a gateway to deliver malware to their victims.

Hunt constantly crawls the internet for open directories, downloading every file on the server, including scripts, which defenders can read (thanks to Hunt) without opening the file.

In this post, I'll provide two recent examples exploring how threat actors leverage open directories to deliver malware to computer systems.

AsyncRAT & BITS

Recently, Hunt identified a malicious IP address serving AsyncRAT that hosted two files in an open directory.

Figure 1: Results of Hunt crawling the open directory at 207.32.217[.]21.

Figure 1: Results of Hunt crawling the open directory at 207.32.217[.]21.Little thought went into naming the files, which could have given us an idea of the actor's intent.

Clicking on the magnifying glass under the "Actions" tab will open a smaller window, allowing us to read the file.

Figure 2: Contents of xx.txt

Figure 2: Contents of xx.txtxx.txt contains VBScript, which does the following:

1 Creates an XML file containing a PowerShell command, saving the file to the system as "temp.xml."

2 Extracts the content within the "" section of the XML file and uses Microsoft BITS (Background Intelligent Transfer Service) to download the file "f.jpg" from the same server.

3 Remove all traces of "temp.xml" from the system using the FileSystemObject command

Naming a file "xx.txt" presumably indicates a placeholder, which the actor may rename uniquely for each campaign or target. Likely, delivery methods could include attaching the text file in a crafted email or as a series of files offered to the victim by other means.

Let's move to a VM and see what's behind f.jpg.

Figure 3: Detect it Easy results of f.jpg

Figure 3: Detect it Easy results of f.jpgf.jpg is a zip file containing 9 additional files. We'll keep digging from here, unzip the file, and see what we find.

Figure 4: Contents of f.jpg

Figure 4: Contents of f.jpgLet's wrap up this first example. If you are analyzing the files at home, let me know what you found.

Python Executable Wrapped in Fernet

The second case is a malicious IP Hunt detected as hosting a login page for Supershell, an open-source C2 platform, and two more files in an open directory.

Figure 5: Hunt results of open directory at 121.37.21[.]229

Figure 5: Hunt results of open directory at 121.37.21[.]229Once again, we have some rather dull file names. 1.exe is rather large at 10 MB, but let's look at a.txt.

Figure 6: Encoded/encrypted data of a.txt.

Figure 6: Encoded/encrypted data of a.txt.The text in the file is encoded or encrypted; we just don't know with what algorithm yet.

Even with a 10MB file, phishing remains a viable delivery method, in addition to hosting the file somewhere as a popular tool for download.

Moving back to our VM, let's look at 1. exe.

Figure 7: Detect it Easy results of 1.exe

Figure 7: Detect it Easy results of 1.exeLet's skip forward and cover the compiled Python files extracted from the executable.

Figure 8: Decompiled code of b.pyc and interesting string

Figure 8: Decompiled code of b.pyc and interesting string Figure 9: decrypted code from a.txt

Figure 9: decrypted code from a.txtFrom Figures 8 & 9, we can see that 1.exe:

Defines a key using the Fernet encryption scheme to decrypt "sectr" stored in "destr."

The inner function, "A" executes the "destr" value.

"T2" Base64 encodes a message in Chinese twice.

"T1" implements the QuickSort algorithm.

Function "00619654()" makes a GET request and downloads a.txt from the open directory, then tries to run the "06936762() function.

From Figures 8 & 9, we can see that 1.exe:

Note: I couldn't find the message in string "t2" used in other malicious code. If you've seen it used before, feel free to reach out on X (Twitter).

As we can see in Figure 9, the result of a.txt is a Python script that decrypts shellcode (encrypted with Fernet) in memory and executes it.

VirusTotal and Triage detect 1.exe and the shellcode as part of the Cobalt Strike penetration testing tool.

Conclusion

As we've explored, exposed directories serve as a common vector for malware delivery and the subsequent loading of additional malicious components. Often overlooked due to the plethora of malware found in directories, it is crucial that we, as defenders, remember that these servers can be the beginning of a bad day for our network.

For further hunting, here are more examples:

Related Posts

Related Posts

Related Posts