The Secret Ingredient: Unearthing Suspected SpiceRAT Infrastructure via HTML Response

The Secret Ingredient: Unearthing Suspected SpiceRAT Infrastructure via HTML Response

Published on

Jul 11, 2024

Reports on new malware families often leave subtle clues that lead researchers to uncover additional infrastructure not highlighted in the initial findings. A recent blog post by Cisco Talos highlighted SpiceRAT, a remote access trojan targeting organizations in Asia, Europe, the Middle East, and Africa.

Inspired by the outstanding research by Ashley Shen and Chetan Raghuprasa, we set out to identify other servers associated with the RAT.

Join us as we unearth suspected SpiceRAT command and control (C2)s, leading to several similar domains to those in Talos’ article.

Insights from Talos’ Research

While an in-depth analysis of the RAT is beyond the scope of this post, I’d like to detail some of SpiceRAT's notable features and functionalities for those unfamiliar. The report attributed the malicious software to a newly discovered group named SneakyChef, who, according to reporting, also has access to the SugarGh0st RAT.

The trojan comprises four components: a legitimate executable, a malicious DLL loader, an unencrypted payload, and various downloaded plugins. Talos identified two infection chains used by SneakyChef to deploy SpiceRAT, an HTA or LNK file.

Upon execution, the malware gathers data from the victim’s machine, including the operating system version, hostname, username, IP address, and MAC address.

The encrypted victim data is sent to the C2 server, which responds with a message surrounded by HTML tags. This communication with the controller caught our attention.

Below is a screenshot from the report explaining the RAT → C2 analysis.

Figure 1: Screenshot from Talos report describing the communication between the C2 and RAT. (Underline added by author)

Figure 1: Screenshot from Talos report describing the communication between the C2 and RAT. (Underline added by author)Our Findings

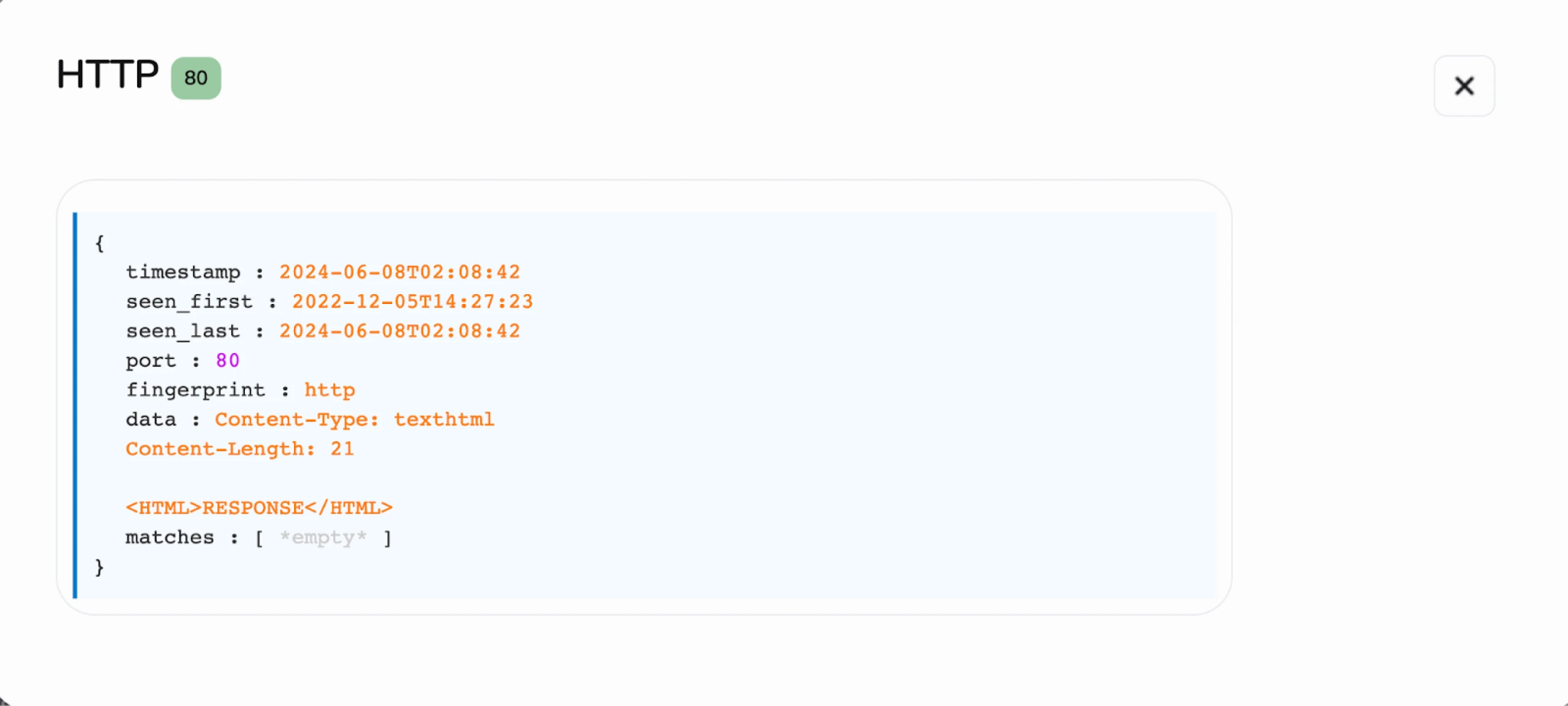

Focusing on the HTML message from the C2 server, we probed how a typical HTTP GET request to the server identified in the report, 94.198.40_4, would respond. That output is shown in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2: Screenshot of C2 response to a GET request. (Try it out here)

Figure 2: Screenshot of C2 response to a GET request. (Try it out here)HTTP Response:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-Type: text/html

Content-Length: 21

<HTML>RESPONSE</HTML>

Armed with this information, we can begin scanning for other servers on the internet exhibiting the same HTTP response pattern. The SHA-1 hash for this HTML content is df608e9587f37a5d7f13deaa99d312b4acda463c.

Our scans revealed five separate IP addresses matching the hash above, with domains similar to those identified by Talos. As of this writing, only one IP, 2.58.14_98, remains active, while the others are historical.

The following section will introduce each IP, its associated domains, and any notable findings.

Uncovering the Infrastructure

Of the five IP addresses we discovered matching the response hash, all but one are hosted on the Starks Industries Solutions network, a frequent haven for cyber criminals and APT groups.

The outlier IP, hosted on Crowncloud, is also known for malicious activities. We’ll begin with 2.58.14_98.

2.58.14_98

SneakyChef targeted the country of Angola with actual documents from a Turkmenistan news agency. As shown in the above screenshot, the domain update.telecom-tm_com closely mimics the legitimate domain of Turkmenistan's telecommunications company, Turkmentelecom EAK, telecom_tm

45.144.31_244

The next IP under examination, 45.144.31_244, resolves to two domains: webmail.roundcube_email and update.mozilia-tm_com—the former domain attempts to spoof the open-source webmail software Roundcube. At the same time, the latter is designed to impersonate an entity connected to Turkmenistan, suggesting an affiliation with Mozilla, the renowned organization behind the Firefox browser.

45.159.250_43

You’ll likely notice the domain in Figure 5 from the report we’ve referenced many times in this post. Looking up this IP in VirusTotal results in a community score of 0, but with a communicating file named ‘chromeupdate.zip,’ also identified as being downloaded from an attacker-controlled server in the Talos article.

The archive file detected as SpiceRAT has a SHA-1 hash of 1bb0a205953c1c86c058bcf428ea15b2f5b25020

Figure 6: VirusTotal results showing the IP with a community score of 0 and a file detected as SpiceRAT seen communicating with it. (VT link for chromeupdate.zip file)

Figure 6: VirusTotal results showing the IP with a community score of 0 and a file detected as SpiceRAT seen communicating with it. (VT link for chromeupdate.zip file)86.104.73_52

Figure 7: Screenshot of 86.104.73_52 with suspicious domain. (Check it out here)

Figure 7: Screenshot of 86.104.73_52 with suspicious domain. (Check it out here)Continuing with the theme of spoofed domains, 86.104.73_52 resolves to zone.webskype_net, likely aimed at Skype users.

94.131.121_56

Figure 8: Overview of 94.131.121_56 in Hunt (Link here)

Figure 8: Overview of 94.131.121_56 in Hunt (Link here)Our final IP, although short-lived, returned the HTML ‘RESPONSE’ message for just one day in March of this year (Figure 9)—the domain site.yoshlar_info suggests a possible connection to Uzbekistan, indicating a broader geographic scope to these attacks, though further investigation is necessary to confirm any links.

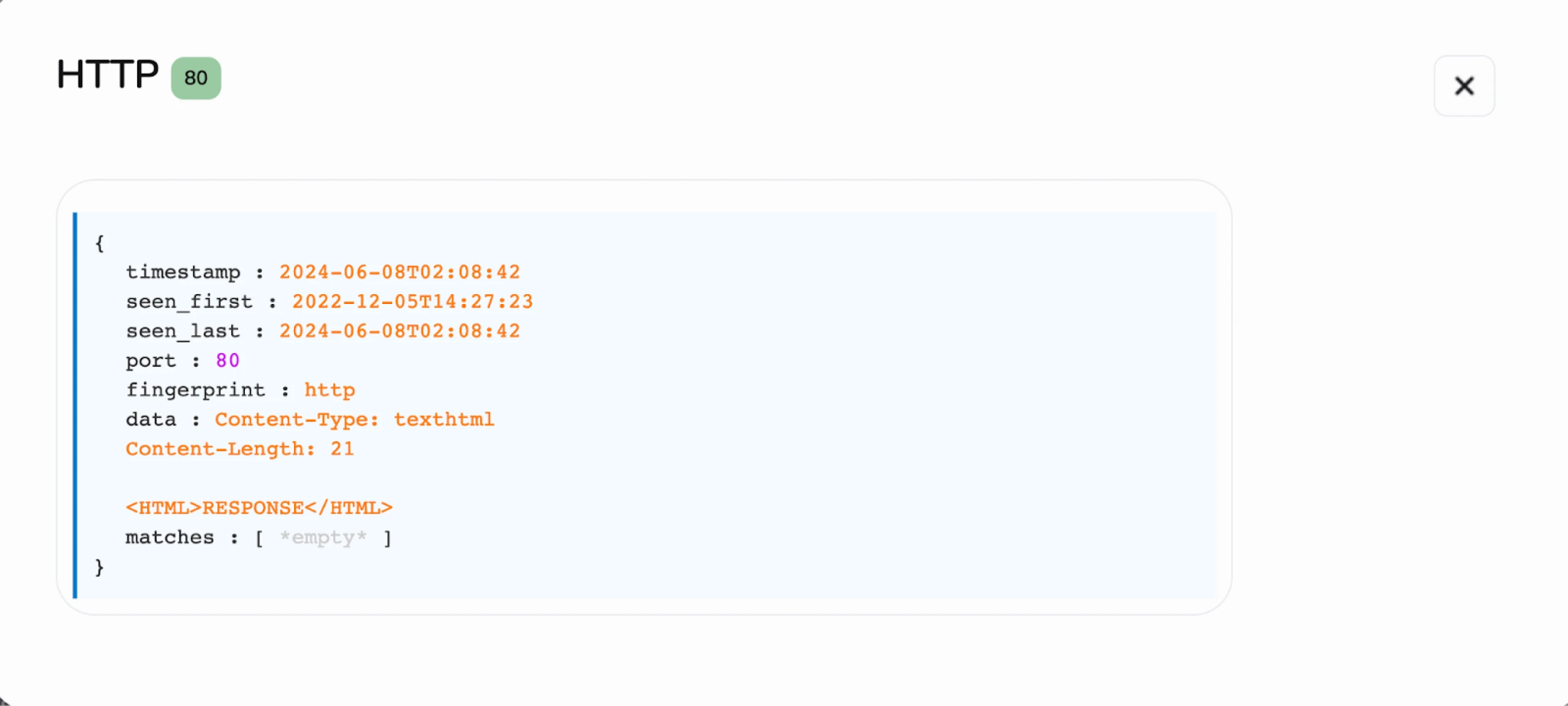

Figure 9: Port 80 HTTP response seen active for one day in March 2024.

Figure 9: Port 80 HTTP response seen active for one day in March 2024.Conclusion

Our analysis of SpiceRAT infrastructure demonstrates the importance of leveraging malware reports to uncover additional command and control servers. These findings can illuminate past infections and targeting patterns, enhancing our understanding of the threat landscape.

Request a free demo today and explore what adversary networks you can unearth with access to over 80 malware, open-source, and red team tools.

Network Observables

HTML Response SHA-1: df608e9587f37a5d7f13deaa99d312b4acda463c

| IP Address | Domain(s) |

|---|---|

| 2.58.14_98 | update.telecom-tm_com |

| 45.144.31_244 | webmail.roundcube_email update.mozilia-tm_com |

| 45.159.250_43 | stock.adobe-service_net |

| 86.104.73_52 | zone.webskype_net |

| 94.131.121_56 | site.yoshlar_info |

Reports on new malware families often leave subtle clues that lead researchers to uncover additional infrastructure not highlighted in the initial findings. A recent blog post by Cisco Talos highlighted SpiceRAT, a remote access trojan targeting organizations in Asia, Europe, the Middle East, and Africa.

Inspired by the outstanding research by Ashley Shen and Chetan Raghuprasa, we set out to identify other servers associated with the RAT.

Join us as we unearth suspected SpiceRAT command and control (C2)s, leading to several similar domains to those in Talos’ article.

Insights from Talos’ Research

While an in-depth analysis of the RAT is beyond the scope of this post, I’d like to detail some of SpiceRAT's notable features and functionalities for those unfamiliar. The report attributed the malicious software to a newly discovered group named SneakyChef, who, according to reporting, also has access to the SugarGh0st RAT.

The trojan comprises four components: a legitimate executable, a malicious DLL loader, an unencrypted payload, and various downloaded plugins. Talos identified two infection chains used by SneakyChef to deploy SpiceRAT, an HTA or LNK file.

Upon execution, the malware gathers data from the victim’s machine, including the operating system version, hostname, username, IP address, and MAC address.

The encrypted victim data is sent to the C2 server, which responds with a message surrounded by HTML tags. This communication with the controller caught our attention.

Below is a screenshot from the report explaining the RAT → C2 analysis.

Figure 1: Screenshot from Talos report describing the communication between the C2 and RAT. (Underline added by author)

Figure 1: Screenshot from Talos report describing the communication between the C2 and RAT. (Underline added by author)Our Findings

Focusing on the HTML message from the C2 server, we probed how a typical HTTP GET request to the server identified in the report, 94.198.40_4, would respond. That output is shown in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2: Screenshot of C2 response to a GET request. (Try it out here)

Figure 2: Screenshot of C2 response to a GET request. (Try it out here)HTTP Response:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-Type: text/html

Content-Length: 21

<HTML>RESPONSE</HTML>

Armed with this information, we can begin scanning for other servers on the internet exhibiting the same HTTP response pattern. The SHA-1 hash for this HTML content is df608e9587f37a5d7f13deaa99d312b4acda463c.

Our scans revealed five separate IP addresses matching the hash above, with domains similar to those identified by Talos. As of this writing, only one IP, 2.58.14_98, remains active, while the others are historical.

The following section will introduce each IP, its associated domains, and any notable findings.

Uncovering the Infrastructure

Of the five IP addresses we discovered matching the response hash, all but one are hosted on the Starks Industries Solutions network, a frequent haven for cyber criminals and APT groups.

The outlier IP, hosted on Crowncloud, is also known for malicious activities. We’ll begin with 2.58.14_98.

2.58.14_98

SneakyChef targeted the country of Angola with actual documents from a Turkmenistan news agency. As shown in the above screenshot, the domain update.telecom-tm_com closely mimics the legitimate domain of Turkmenistan's telecommunications company, Turkmentelecom EAK, telecom_tm

45.144.31_244

The next IP under examination, 45.144.31_244, resolves to two domains: webmail.roundcube_email and update.mozilia-tm_com—the former domain attempts to spoof the open-source webmail software Roundcube. At the same time, the latter is designed to impersonate an entity connected to Turkmenistan, suggesting an affiliation with Mozilla, the renowned organization behind the Firefox browser.

45.159.250_43

You’ll likely notice the domain in Figure 5 from the report we’ve referenced many times in this post. Looking up this IP in VirusTotal results in a community score of 0, but with a communicating file named ‘chromeupdate.zip,’ also identified as being downloaded from an attacker-controlled server in the Talos article.

The archive file detected as SpiceRAT has a SHA-1 hash of 1bb0a205953c1c86c058bcf428ea15b2f5b25020

Figure 6: VirusTotal results showing the IP with a community score of 0 and a file detected as SpiceRAT seen communicating with it. (VT link for chromeupdate.zip file)

Figure 6: VirusTotal results showing the IP with a community score of 0 and a file detected as SpiceRAT seen communicating with it. (VT link for chromeupdate.zip file)86.104.73_52

Figure 7: Screenshot of 86.104.73_52 with suspicious domain. (Check it out here)

Figure 7: Screenshot of 86.104.73_52 with suspicious domain. (Check it out here)Continuing with the theme of spoofed domains, 86.104.73_52 resolves to zone.webskype_net, likely aimed at Skype users.

94.131.121_56

Figure 8: Overview of 94.131.121_56 in Hunt (Link here)

Figure 8: Overview of 94.131.121_56 in Hunt (Link here)Our final IP, although short-lived, returned the HTML ‘RESPONSE’ message for just one day in March of this year (Figure 9)—the domain site.yoshlar_info suggests a possible connection to Uzbekistan, indicating a broader geographic scope to these attacks, though further investigation is necessary to confirm any links.

Figure 9: Port 80 HTTP response seen active for one day in March 2024.

Figure 9: Port 80 HTTP response seen active for one day in March 2024.Conclusion

Our analysis of SpiceRAT infrastructure demonstrates the importance of leveraging malware reports to uncover additional command and control servers. These findings can illuminate past infections and targeting patterns, enhancing our understanding of the threat landscape.

Request a free demo today and explore what adversary networks you can unearth with access to over 80 malware, open-source, and red team tools.

Network Observables

HTML Response SHA-1: df608e9587f37a5d7f13deaa99d312b4acda463c

| IP Address | Domain(s) |

|---|---|

| 2.58.14_98 | update.telecom-tm_com |

| 45.144.31_244 | webmail.roundcube_email update.mozilia-tm_com |

| 45.159.250_43 | stock.adobe-service_net |

| 86.104.73_52 | zone.webskype_net |

| 94.131.121_56 | site.yoshlar_info |

Related Posts

Related Posts

Related Posts

©2026 Hunt Intelligence, Inc.

©2026 Hunt Intelligence, Inc.

©2025 Hunt Intelligence, Inc.