Unearthing New Infrastructure by Revisiting Past Threat Reports

Published on

Introduction

Suppose you know David Bianco's "Pyramid of Pain" model. In that case, you know that IP addresses are among the lower indicators of compromise due to their short lifespan and ease of change to legitimate purposes.

However, IP-based intelligence offers valuable insights when examining commonalities (open directories, ports, etc.) across ASNs.

One way of gathering this information is by revisiting past threat reports. In this post, we'll explore how examining IP addresses from historical vendor reports can lead to discovering new attacker infrastructure, providing a window into evolving threats.

Starting Point: The Blog Post

The post we'll be referencing today is on secrss.com and details a phishing campaign attributed to the Silver Fox group targeting Chinese users with the standard GhostRAT malware and a variant first introduced on the t00ls forum dubbed "winos."

Figure 1: Screenshot of Silver Fox blog post (Source: https://www.secrss.com/articles/60688)

Figure 1: Screenshot of Silver Fox blog post (Source: https://www.secrss.com/articles/60688)The article (published Nov 2023) provides many IP addresses and ports that we could use to find similar infrastructure within the same ASN. Instead, we will look for open directories within some of these networks and see what interesting files await our analysis.

Figure 2: Just a few of the IPs found in the Secrss article

Figure 2: Just a few of the IPs found in the Secrss articleThe article on SECRSS delves into the "Silver Fox" cybercriminal group's detailed operations. So what exactly happened?

The Silver Fox group's recent phishing campaign targeted Chinese users and companies through different malicious techniques. Among those techniques, they used SEO (Search Engine Optimization) to make sure their phishing sites rank highly in Chinese search engine results.

With SEO, they used malicious ads and multiple email phishing campaigns to distribute Remote Administration Trojans (RATs) malwares (Gh0st RAT, ValleyRAT, and Sainbox RAT).

When people searched on google.cn or Telegram for example, they would get redirected to google.com.hk to receive uncensored search results filled with malicious ads, possibly from these threat actors.

Figure 3: Search results showing malicious ads on google.com.hk that invite people to download the Telegram app

Figure 3: Search results showing malicious ads on google.com.hk that invite people to download the Telegram appOnce people got phished and the group claimed access to a company's network, they disseminated the trojanized files through WeChat groups to other employees.

The Silver Fox group employed a range of Asia-based ASNs, including Tencent, CTG Server Ltd., and TCloudnet, to host its infrastructure. The section below discusses several files, from a PurpleFox rootkit sample to a few obfuscated files that lead to Python and ELF-based Meterpreter payloads.

192.253.234[.]80:8000 (CTG Server Ltd.)

Figure 4: CTG Server Ltd. hosted open directory

Figure 4: CTG Server Ltd. hosted open directoryThe file named "0" is a Base64 and Gzip compressed PowerShell script, detected as an Empire implant according to VirusTotal. If you guessed that the names of the other two files correlate with the port each communicates with, you'd be correct.

As shown in Figure 4 below, file 47478.elf was detected by 33 vendors.

Figure 5: VirusTotal screenshot of 47478.elf

Figure 5: VirusTotal screenshot of 47478.elfBy contrast, the highly obfuscated 47477.py was only detected by 6 vendors. A snippet of the script is below.

Figure 6: Snippet of 47477.py

Figure 6: Snippet of 47477.pyFigure 6 depicts the script in CyberChef. We can easily decode it. However, additional obfuscated code is also within the code, copied directly from the Metasploit GitHub.

Figure 7: Snippet of deobfuscated Python code (Source: CyberChef)

Figure 7: Snippet of deobfuscated Python code (Source: CyberChef)Hashes

| Filename | SHA1 |

|---|---|

| 0.ps1 | f20d5e4417061e5d86a11f601f2368a91cb7847c |

| 47477.py | 981e6c1a002636b24810863357d7cc34b04e79c3 |

| 47478.elf | 981e6c1a002636b24810863357d7cc34b04e79c3 |

Although the analyzed files might not be directly linked to the Silver Fox group, they offer valuable insight into other threat actors operating within the same ASN. This connection gives researchers and defenders a clearer understanding of the potential threats residing within specific network blocks, aiding their efforts to anticipate and mitigate risks.

206.238.196[.]240:80 (TERAEXCH/Tcloudnet)

Although HTTP File Server (HFS) instances are not well known in open directory research, many contain a wealth of information, hosting some widely known malware and some less known. If you haven't added HFS servers to your research, I suggest doing so today.

Figure 8: Screenshot of open directory at 206.238.196[.]240

Figure 8: Screenshot of open directory at 206.238.196[.]240The file identified in this directory is a 32-bit Nullsoft Scriptable Install System (NSIS) Windows executable employing SEProtect for obfuscation. Although detected as PurpleFox, this executable also executes GhostRAT, reflecting tactics similar to those detailed in the Secrss article.

Figure 9: Sandbox results of mngboot.exe (Source: https://tria.ge/240423-jj2wbsef4w/behavioral2)

Figure 9: Sandbox results of mngboot.exe (Source: https://tria.ge/240423-jj2wbsef4w/behavioral2)In addition to the exposed server querying the IP in Hunt, as recently as a few days ago, this same IP was also hosting AsyncRAT.

Figure 10: Hunt IP History -- 206.238.196[.]240

Figure 10: Hunt IP History -- 206.238.196[.]240File Hash

| Filename | SHA1 |

|---|---|

| mngboot.exe | 9fe8436f8e1f6198b883404f0b59256b4f08bbed |

Uncovering Attacks and Threats

In this brief overview, we've demonstrated how researchers can leverage historical threat reports to uncover attacker infrastructure before it is actively employed in malicious campaigns.

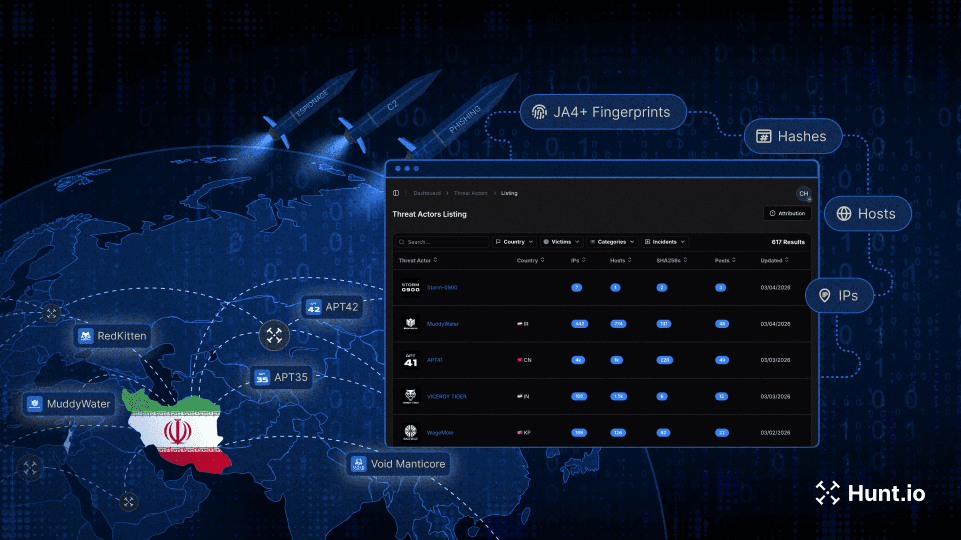

Explore the past to identify future threats. By signing up for a Hunt account, you can join our efforts to track down concealed attacker infrastructure. This proactive approach helps us better understand emerging cybersecurity risks and take steps to mitigate them.

Introduction

Suppose you know David Bianco's "Pyramid of Pain" model. In that case, you know that IP addresses are among the lower indicators of compromise due to their short lifespan and ease of change to legitimate purposes.

However, IP-based intelligence offers valuable insights when examining commonalities (open directories, ports, etc.) across ASNs.

One way of gathering this information is by revisiting past threat reports. In this post, we'll explore how examining IP addresses from historical vendor reports can lead to discovering new attacker infrastructure, providing a window into evolving threats.

Starting Point: The Blog Post

The post we'll be referencing today is on secrss.com and details a phishing campaign attributed to the Silver Fox group targeting Chinese users with the standard GhostRAT malware and a variant first introduced on the t00ls forum dubbed "winos."

Figure 1: Screenshot of Silver Fox blog post (Source: https://www.secrss.com/articles/60688)

Figure 1: Screenshot of Silver Fox blog post (Source: https://www.secrss.com/articles/60688)The article (published Nov 2023) provides many IP addresses and ports that we could use to find similar infrastructure within the same ASN. Instead, we will look for open directories within some of these networks and see what interesting files await our analysis.

Figure 2: Just a few of the IPs found in the Secrss article

Figure 2: Just a few of the IPs found in the Secrss articleThe article on SECRSS delves into the "Silver Fox" cybercriminal group's detailed operations. So what exactly happened?

The Silver Fox group's recent phishing campaign targeted Chinese users and companies through different malicious techniques. Among those techniques, they used SEO (Search Engine Optimization) to make sure their phishing sites rank highly in Chinese search engine results.

With SEO, they used malicious ads and multiple email phishing campaigns to distribute Remote Administration Trojans (RATs) malwares (Gh0st RAT, ValleyRAT, and Sainbox RAT).

When people searched on google.cn or Telegram for example, they would get redirected to google.com.hk to receive uncensored search results filled with malicious ads, possibly from these threat actors.

Figure 3: Search results showing malicious ads on google.com.hk that invite people to download the Telegram app

Figure 3: Search results showing malicious ads on google.com.hk that invite people to download the Telegram appOnce people got phished and the group claimed access to a company's network, they disseminated the trojanized files through WeChat groups to other employees.

The Silver Fox group employed a range of Asia-based ASNs, including Tencent, CTG Server Ltd., and TCloudnet, to host its infrastructure. The section below discusses several files, from a PurpleFox rootkit sample to a few obfuscated files that lead to Python and ELF-based Meterpreter payloads.

192.253.234[.]80:8000 (CTG Server Ltd.)

Figure 4: CTG Server Ltd. hosted open directory

Figure 4: CTG Server Ltd. hosted open directoryThe file named "0" is a Base64 and Gzip compressed PowerShell script, detected as an Empire implant according to VirusTotal. If you guessed that the names of the other two files correlate with the port each communicates with, you'd be correct.

As shown in Figure 4 below, file 47478.elf was detected by 33 vendors.

Figure 5: VirusTotal screenshot of 47478.elf

Figure 5: VirusTotal screenshot of 47478.elfBy contrast, the highly obfuscated 47477.py was only detected by 6 vendors. A snippet of the script is below.

Figure 6: Snippet of 47477.py

Figure 6: Snippet of 47477.pyFigure 6 depicts the script in CyberChef. We can easily decode it. However, additional obfuscated code is also within the code, copied directly from the Metasploit GitHub.

Figure 7: Snippet of deobfuscated Python code (Source: CyberChef)

Figure 7: Snippet of deobfuscated Python code (Source: CyberChef)Hashes

| Filename | SHA1 |

|---|---|

| 0.ps1 | f20d5e4417061e5d86a11f601f2368a91cb7847c |

| 47477.py | 981e6c1a002636b24810863357d7cc34b04e79c3 |

| 47478.elf | 981e6c1a002636b24810863357d7cc34b04e79c3 |

Although the analyzed files might not be directly linked to the Silver Fox group, they offer valuable insight into other threat actors operating within the same ASN. This connection gives researchers and defenders a clearer understanding of the potential threats residing within specific network blocks, aiding their efforts to anticipate and mitigate risks.

206.238.196[.]240:80 (TERAEXCH/Tcloudnet)

Although HTTP File Server (HFS) instances are not well known in open directory research, many contain a wealth of information, hosting some widely known malware and some less known. If you haven't added HFS servers to your research, I suggest doing so today.

Figure 8: Screenshot of open directory at 206.238.196[.]240

Figure 8: Screenshot of open directory at 206.238.196[.]240The file identified in this directory is a 32-bit Nullsoft Scriptable Install System (NSIS) Windows executable employing SEProtect for obfuscation. Although detected as PurpleFox, this executable also executes GhostRAT, reflecting tactics similar to those detailed in the Secrss article.

Figure 9: Sandbox results of mngboot.exe (Source: https://tria.ge/240423-jj2wbsef4w/behavioral2)

Figure 9: Sandbox results of mngboot.exe (Source: https://tria.ge/240423-jj2wbsef4w/behavioral2)In addition to the exposed server querying the IP in Hunt, as recently as a few days ago, this same IP was also hosting AsyncRAT.

Figure 10: Hunt IP History -- 206.238.196[.]240

Figure 10: Hunt IP History -- 206.238.196[.]240File Hash

| Filename | SHA1 |

|---|---|

| mngboot.exe | 9fe8436f8e1f6198b883404f0b59256b4f08bbed |

Uncovering Attacks and Threats

In this brief overview, we've demonstrated how researchers can leverage historical threat reports to uncover attacker infrastructure before it is actively employed in malicious campaigns.

Explore the past to identify future threats. By signing up for a Hunt account, you can join our efforts to track down concealed attacker infrastructure. This proactive approach helps us better understand emerging cybersecurity risks and take steps to mitigate them.

Related Posts

Related Posts

Related Posts