Discovering & Disrupting Malicious Infrastructure

Published on

The term "threat hunting" is generally associated with detecting malicious behavior on endpoints manually or via automated tools.

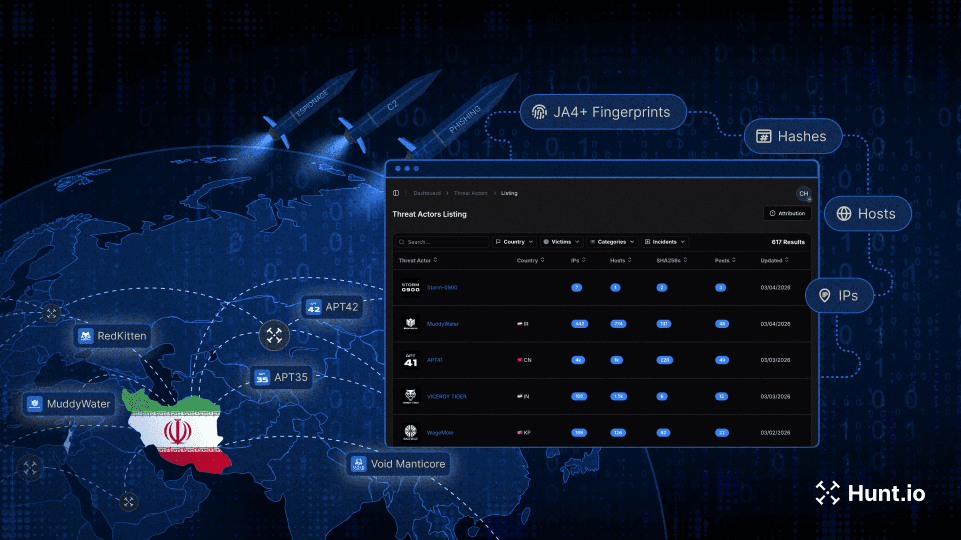

In this post, we'll do something different and showcase how the Hunt platform can be leveraged to proactively identify infrastructure not yet publicly reported on from recent malware campaigns and search open directories hosting logs and malware not widely seen.

Advanced Search For Advanced Threats

First, we'll leverage existing threat research by Microsoft Threat Intelligence disclosing TTPs by the Flax Typhoon threat actor to see if we can identify additional infrastructure not reported on using Hunt's Advanced Search feature.

In the report, Microsoft noted Flax Typhoon's preference for hosting SoftEther VPN servers on their infrastructure instead of a third party. The information included the Common Name, or CN, for the associated TLS certificates of those servers.

Advanced Search's schema is self-explanatory; examples are below the query box for quick reference and the data schema below.

In addition to single queries on certificates and malware, users can string multiple queries together using the "AND" & "OR" operators.

We'll start our hunt using the "subject.common_name" field and add the common name values provided in the report.

Some results repeat as certificates appear on the same server at different times. Still, we have 4 IP addresses that did not appear in Microsoft's report.

The results may or may not be associated with the campaign, but with such a small number of servers returned, they require a glance.

Clicking on any one of the IP addresses will take us to an overview page containing hosting provider information, open ports, passive DNS data, and historical TLS certificate data.

The most exciting feature, in my opinion, of the overview page is the History section. Although still in Beta, this section displays a timeline of malware and certificates hosted on the server.

An example timeline graph for one of the IP addresses returned from our search, 154.55.135[.]119, can be seen below.

We'll end our hunt here to avoid going down a rabbit hole, but hopefully, you can see how quickly we were able to identify suspect infrastructure in a matter of a few clicks.

Keyword Searches (Cobalt) Strike Gold

Hunt's platform allows users to perform keyword searches for files across hundreds of exposed servers. The files are available for download by clicking the download button in the Labels column (see below screenshot).

We'll begin our hunt looking for Cobalt Strike events.log files, which, as the name suggests, contain the date and time the operator connected to the team server and, of the most interest, the IP address that made the connection.

Nearly 250 results would keep us busy for some time. The "cat_server_2023-05-01" folder seems interesting, so let's move to a VM and see what we can find.

The log file presents a few additional items that may require further investigation. Of interest, the operator's IP address is present (obscured to prevent abuse), as well as executable file names: artifact.exe, a100.exe, & a10000.

We could return to the Hunt platform and ascertain if any other open directories are hosting these files. For now, let's keep perusing the files on the server.

The actor had multiple OPSEC mistakes; several essential files were left exposed: the public and private keys stored in cobaltstrike.beacon_keys, a database file for the beacon, and team server profile information.

I'll leave the investigation of the remaining files and folders to the reader.

Within the logs folders, we also have access to the plaintext beacon logs from the team server.

Beacon logs contain every beacon command and its output. In other words, we now have an over-the-shoulder view of the actor navigating the Cobalt Strike console and a possible objective (ransomware, credential gathering, espionage, etc.).

Below is an obscured beacon log pulled from the server.

Once again, we see the operator's IP address used to connect to the team server; more importantly, we can also see that credential gathering is at least one part of the actor's objectives.

The astute reader may have noticed the multiple references to "cat" within the server's folders and files. The demo.cna file contains the string "Hello, cobalt strike[cat]," which shows that this may not be a standard or even cracked Cobalt Strike instance.

In June of this year, EclecticIQ researchers released a blog post identifying a modified version of Cobalt Strike targeting the Taiwanese government and critical infrastructure entities named "Cobalt Strike Cat."

The TTP's cited in the report, most notably an exposed server with multiple lateral movement and reconnaissance tools, give us moderate confidence that we have identified additional Cobalt Strike Cat infrastructure not previously reported on.

Our hunt initially focused on Cobalt Strike events.log files, and now we have stumbled upon a modified version of the tool, which is only accessible to a small community.

Utilizing the keyword search and the ability to download files, as well as the tools in the IP address overview, can assist in proactively identifying malicious infrastructure before operational and keep the community aware of new threats as they appear.

The term "threat hunting" is generally associated with detecting malicious behavior on endpoints manually or via automated tools.

In this post, we'll do something different and showcase how the Hunt platform can be leveraged to proactively identify infrastructure not yet publicly reported on from recent malware campaigns and search open directories hosting logs and malware not widely seen.

Advanced Search For Advanced Threats

First, we'll leverage existing threat research by Microsoft Threat Intelligence disclosing TTPs by the Flax Typhoon threat actor to see if we can identify additional infrastructure not reported on using Hunt's Advanced Search feature.

In the report, Microsoft noted Flax Typhoon's preference for hosting SoftEther VPN servers on their infrastructure instead of a third party. The information included the Common Name, or CN, for the associated TLS certificates of those servers.

Advanced Search's schema is self-explanatory; examples are below the query box for quick reference and the data schema below.

In addition to single queries on certificates and malware, users can string multiple queries together using the "AND" & "OR" operators.

We'll start our hunt using the "subject.common_name" field and add the common name values provided in the report.

Some results repeat as certificates appear on the same server at different times. Still, we have 4 IP addresses that did not appear in Microsoft's report.

The results may or may not be associated with the campaign, but with such a small number of servers returned, they require a glance.

Clicking on any one of the IP addresses will take us to an overview page containing hosting provider information, open ports, passive DNS data, and historical TLS certificate data.

The most exciting feature, in my opinion, of the overview page is the History section. Although still in Beta, this section displays a timeline of malware and certificates hosted on the server.

An example timeline graph for one of the IP addresses returned from our search, 154.55.135[.]119, can be seen below.

We'll end our hunt here to avoid going down a rabbit hole, but hopefully, you can see how quickly we were able to identify suspect infrastructure in a matter of a few clicks.

Keyword Searches (Cobalt) Strike Gold

Hunt's platform allows users to perform keyword searches for files across hundreds of exposed servers. The files are available for download by clicking the download button in the Labels column (see below screenshot).

We'll begin our hunt looking for Cobalt Strike events.log files, which, as the name suggests, contain the date and time the operator connected to the team server and, of the most interest, the IP address that made the connection.

Nearly 250 results would keep us busy for some time. The "cat_server_2023-05-01" folder seems interesting, so let's move to a VM and see what we can find.

The log file presents a few additional items that may require further investigation. Of interest, the operator's IP address is present (obscured to prevent abuse), as well as executable file names: artifact.exe, a100.exe, & a10000.

We could return to the Hunt platform and ascertain if any other open directories are hosting these files. For now, let's keep perusing the files on the server.

The actor had multiple OPSEC mistakes; several essential files were left exposed: the public and private keys stored in cobaltstrike.beacon_keys, a database file for the beacon, and team server profile information.

I'll leave the investigation of the remaining files and folders to the reader.

Within the logs folders, we also have access to the plaintext beacon logs from the team server.

Beacon logs contain every beacon command and its output. In other words, we now have an over-the-shoulder view of the actor navigating the Cobalt Strike console and a possible objective (ransomware, credential gathering, espionage, etc.).

Below is an obscured beacon log pulled from the server.

Once again, we see the operator's IP address used to connect to the team server; more importantly, we can also see that credential gathering is at least one part of the actor's objectives.

The astute reader may have noticed the multiple references to "cat" within the server's folders and files. The demo.cna file contains the string "Hello, cobalt strike[cat]," which shows that this may not be a standard or even cracked Cobalt Strike instance.

In June of this year, EclecticIQ researchers released a blog post identifying a modified version of Cobalt Strike targeting the Taiwanese government and critical infrastructure entities named "Cobalt Strike Cat."

The TTP's cited in the report, most notably an exposed server with multiple lateral movement and reconnaissance tools, give us moderate confidence that we have identified additional Cobalt Strike Cat infrastructure not previously reported on.

Our hunt initially focused on Cobalt Strike events.log files, and now we have stumbled upon a modified version of the tool, which is only accessible to a small community.

Utilizing the keyword search and the ability to download files, as well as the tools in the IP address overview, can assist in proactively identifying malicious infrastructure before operational and keep the community aware of new threats as they appear.

Related Posts

Related Posts

Related Posts