Inside DPRK Operations: New Lazarus and Kimsuky Infrastructure Uncovered Across Global Campaigns

Inside DPRK Operations: New Lazarus and Kimsuky Infrastructure Uncovered Across Global Campaigns

Published on

Research Overview

Note: This report is the result of a collaborative investigation between Hunt.io and the Acronis Threat Research Unit, where both teams collaborated to map ongoing DPRK infrastructure activity, including Lazarus and Kimsuky.

Throughout the analysis, we surfaced clusters of operational assets that had not been connected publicly before, revealing active tool-staging servers, credential theft environments, FRP tunneling nodes, and certificate-linked infrastructure fabric controlled by DPRK operators.

These findings help outline how different parts of the DPRK operational infrastructure continue to intersect across campaigns and provide defenders with clearer visibility into the infrastructure habits these actors rely on.

Introduction

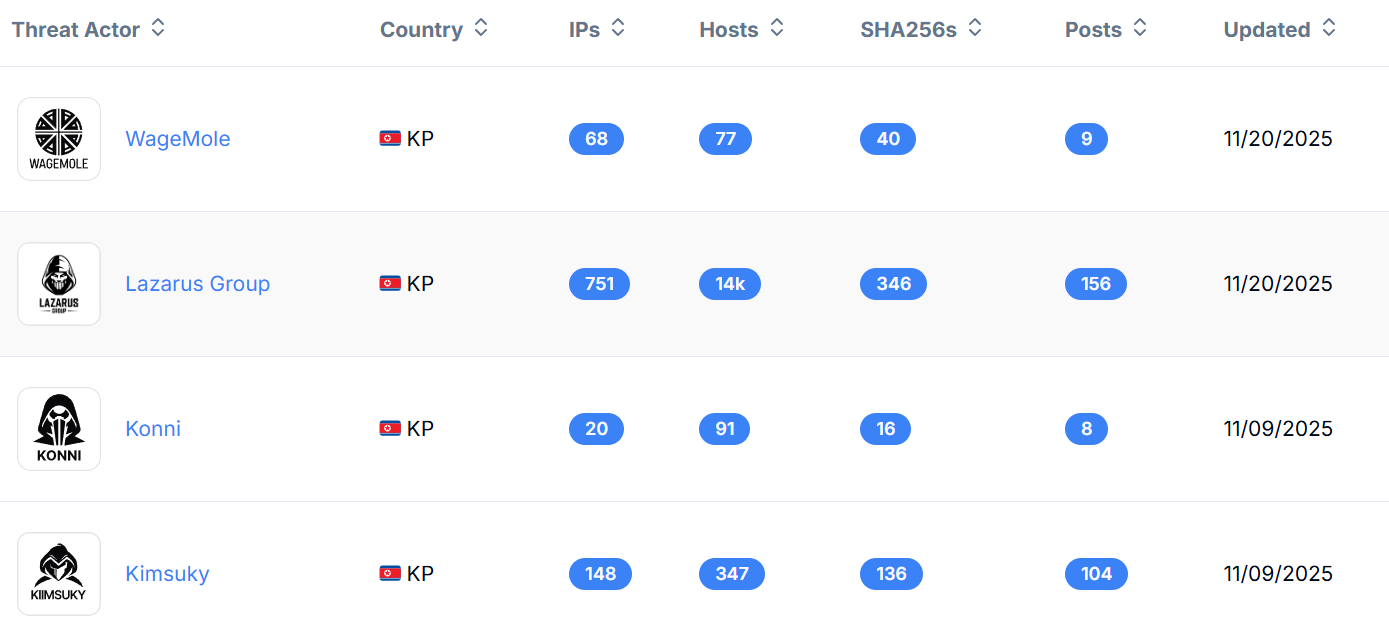

North Korean state-sponsored attackers run one of the most active operations globally, using hacking for intelligence, revenue, and access. Groups like Lazarus, Kimsuky, and other subgroups make up the DPRK threat ecosystem, each running its own playbook ranging from espionage and financial operations to destructive activities. Despite differences in each group’s playbook and motivation, they often share toolkits such as credential harvesting tools, exhibit similar infrastructure patterns, and rely on comparable delivery lures.

Across their multiple campaigns over the years, DPRK threat actors follow consistent operational patterns that make their activity detectable despite evolving malware and lures. One of the most reliable ways to track these actors is through the infrastructure they leave behind. Even when malware families change, the groups often reuse the same infrastructure from their previous campaign. This pattern makes it possible to pivot across indicators, uncover related infrastructures, tooling, and activity that tie their operations together.

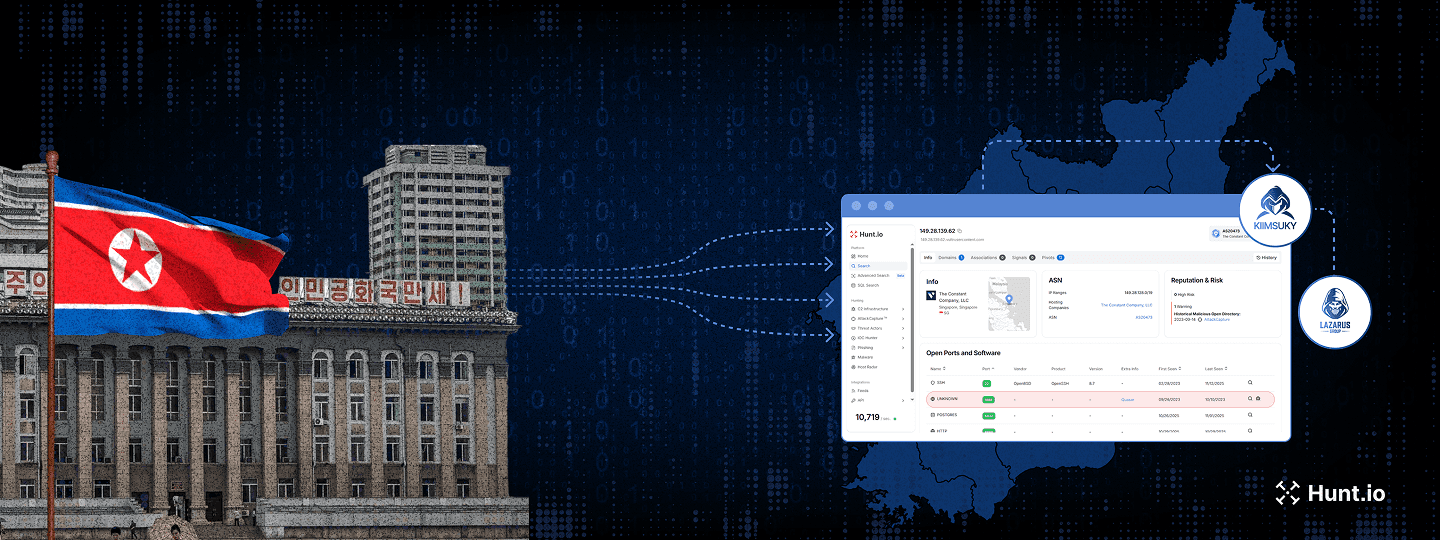

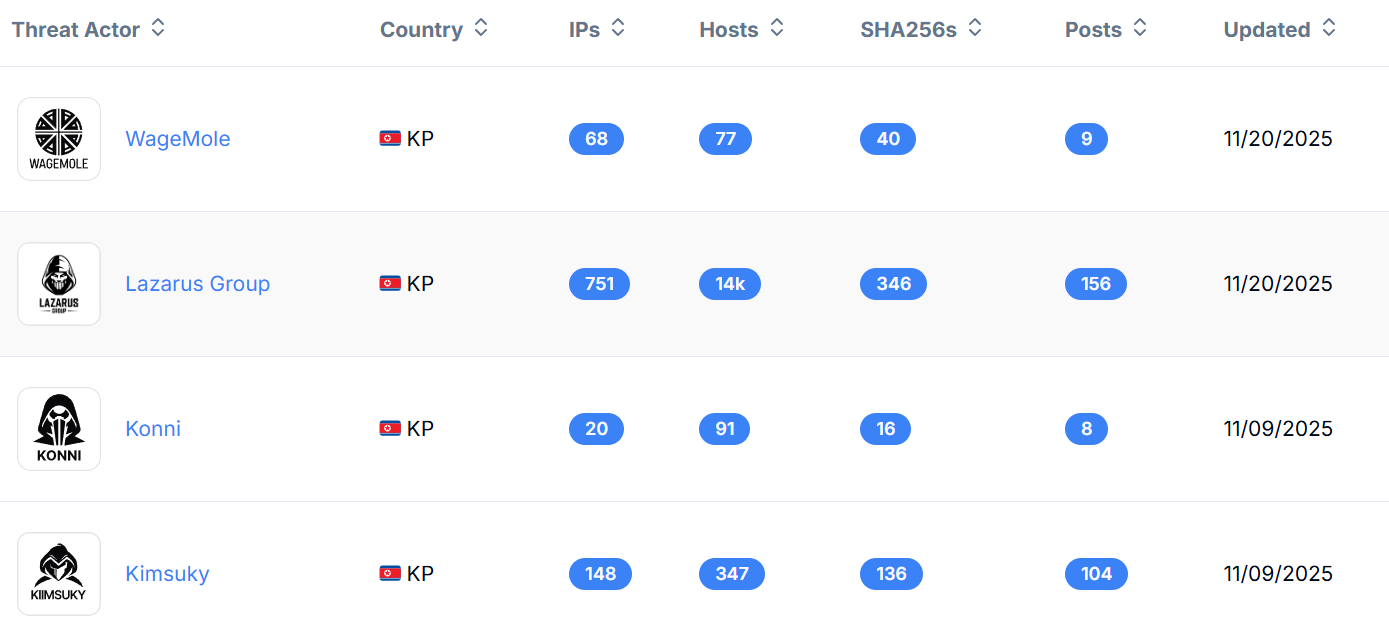

In this research, we used the Hunt.io Threat Actor intelligence to pivot across several DPRK-linked cases to uncover a broader network of DPRK activities. The hunting process is focused on pivoting through IPs, open directories, certificates, and hashes, revealing operator habits across different campaigns. This approach reveals how separate incidents are connected and highlights the consistent operational behaviors of DPRK threat actors.

Fig. 01: Overview of DPRK operational IOCs on the Hunt.io dashboard

Fig. 01: Overview of DPRK operational IOCs on the Hunt.io dashboardOperational Patterns Overview

Across the four hunts, we encountered the same DPRK habits: open directories used as quick staging nodes, repeated deployment of credential theft kits, FRP tunnels running on identical ports across multiple VPS hosts, and certificate reuse that links separate clusters back to the same operators. These patterns stay stable even when the malware or lures change.

From a MITRE ATT&CK perspective, the exposed toolkits fall under Credential Access and Resource Development, the FRP activity aligns with Command and Control, and the certificate pivots reflect the infrastructure choices DPRK groups use for Defense Evasion and long-term access. Once you look at their operations through infrastructure instead of payloads, their workflow becomes much clearer.

These recurring signals are why these clusters can be tracked. Shared hashes, identical directory layouts, certificate patterns, and repeated hosting choices often reveal new infrastructure before it is used in a campaign. The hunts below walk through how these patterns surfaced in practice.

These patterns guided the first hunt into recent Kimsuky and Lazarus activity.

Hunt #1 - Infrastructure Pivoting on DPRK Clusters: Linking Kimsuky and Lazarus Activity

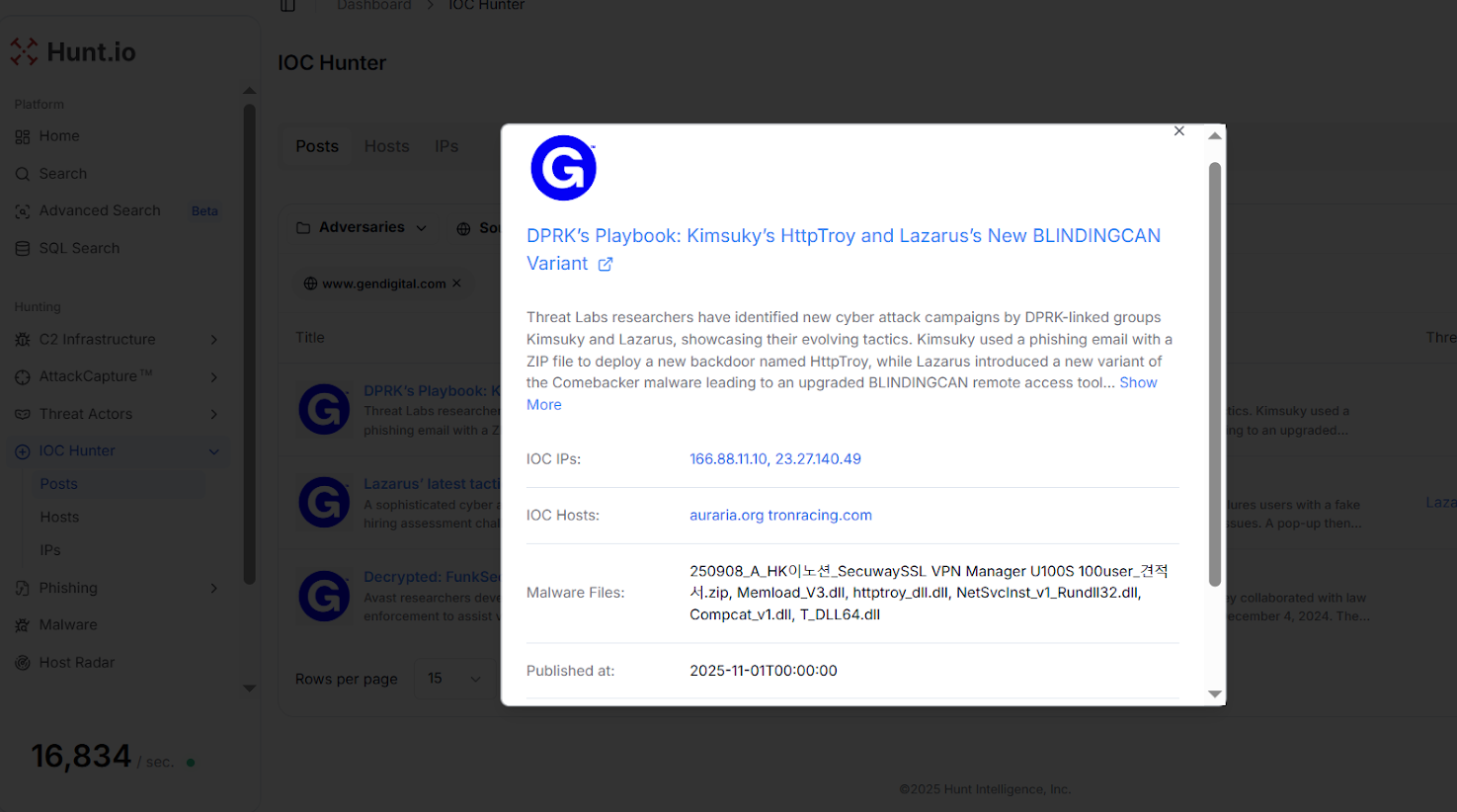

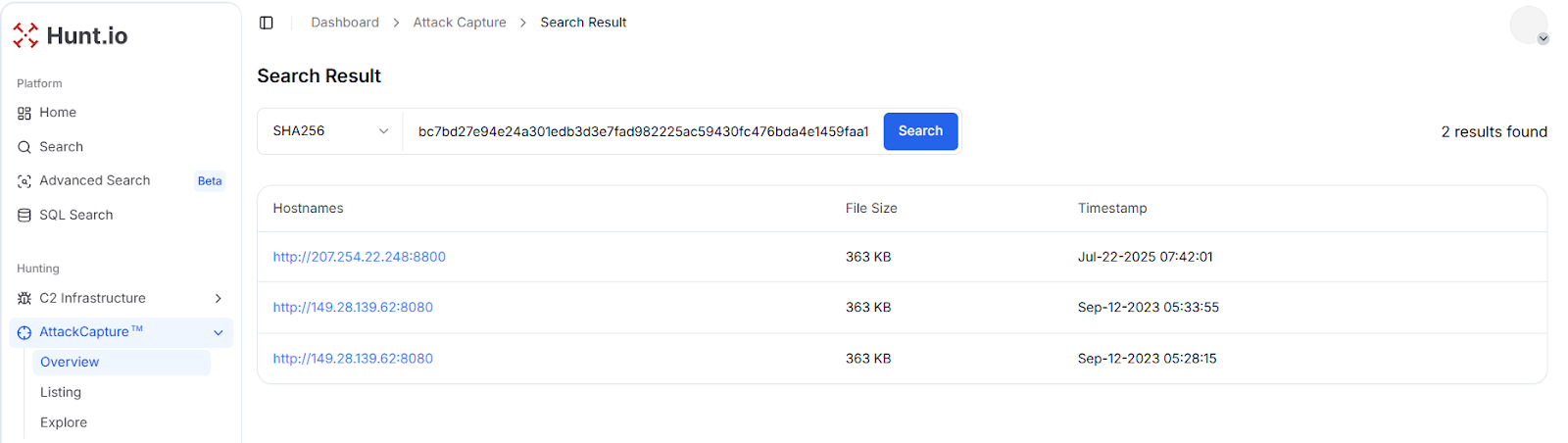

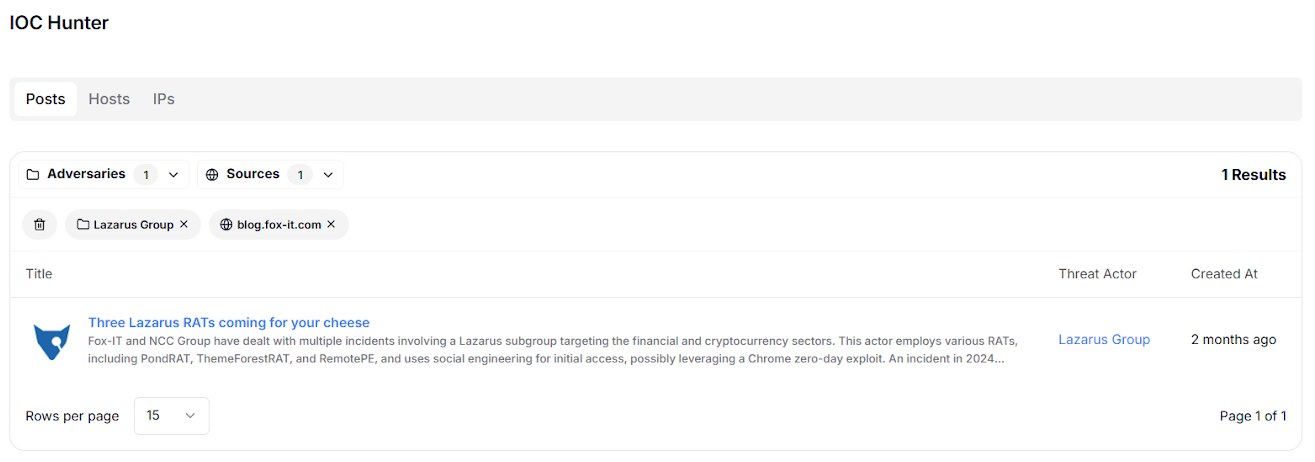

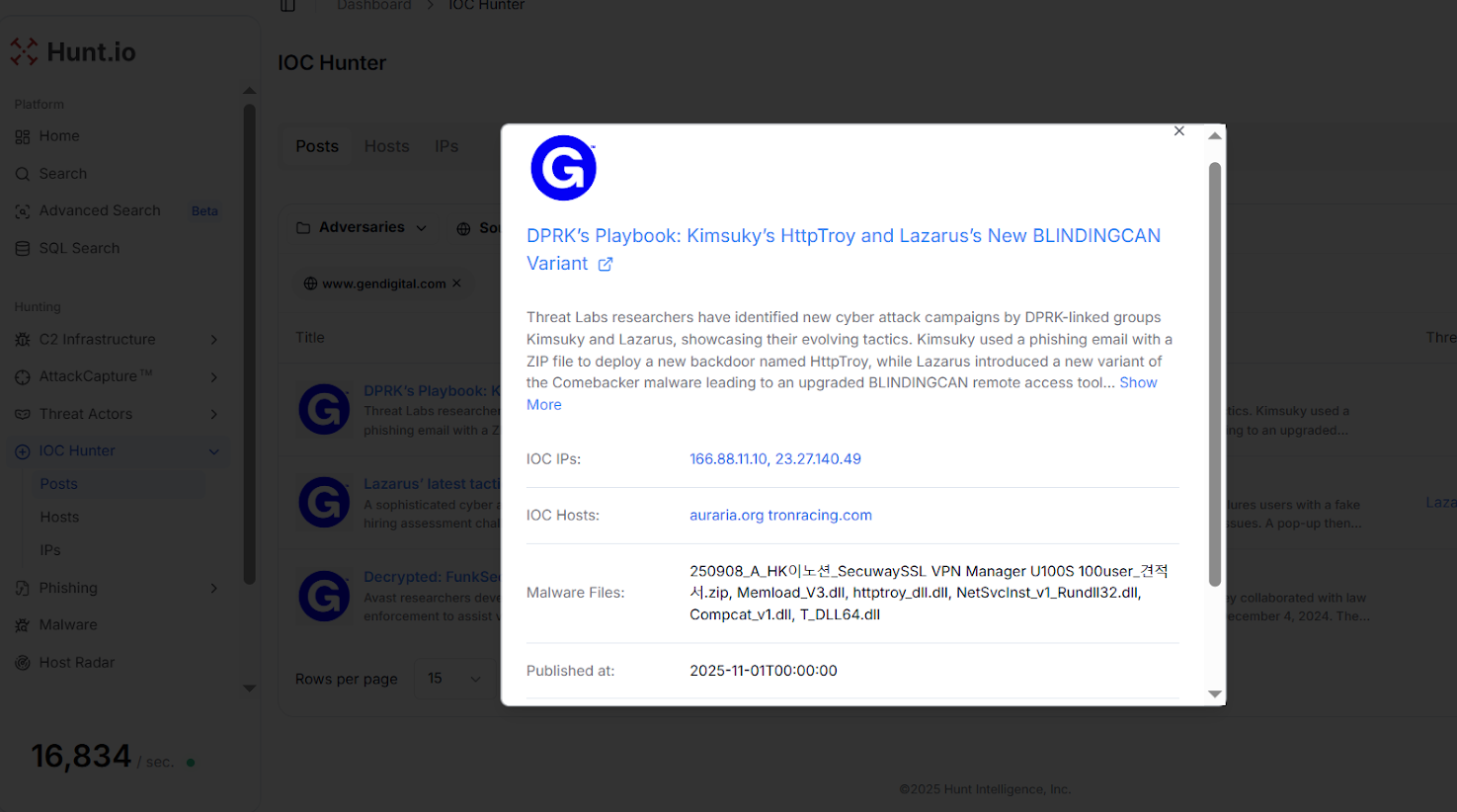

We started hunting DPRK APTs using IOC Hunter, applying the Lazarus Group filter. Then picked up a blog "DPRK's Playbook: Kimsuky's HttpTroy and Lazarus's New BLINDINGCAN Variant" that highlights a recent investigation linked to the Lazarus Group.

Fig. 02: IOC Hunter showing the source article data for 'DPRK's Playbook: Kimsuky's HttpTroy and Lazarus's New BLINDINGCAN Variant'

Fig. 02: IOC Hunter showing the source article data for 'DPRK's Playbook: Kimsuky's HttpTroy and Lazarus's New BLINDINGCAN Variant'Gen Digital's Threat Labs dissected two recent cyber-espionage campaigns conducted by the Kimsuky and Lazarus Group. The first campaign, attributed to Kimsuky, leveraged a VPN-invoice themed ZIP lure to drop a loader ("MemLoad") and a new backdoor dubbed "HttpTroy".

The second, attributed to Lazarus Group, captured a multi-stage intrusion chain culminating in an enhanced version of their BLINDINGCAN remote access tool, signifying the group's continued evolution in obfuscation and stealth.

Using Hunt.io, we tracked one of the IP addresses "23.27.140[.]49" that has an open directory on port 8080. This server was captured by AttackCapture™ on 2025-11-03, prior to other researchers beginning to report related indicators. The open directory shows a single ELF file:

File name: nvd

SHA256:a3876a2492f3c069c0c2b2f155b4c420d8722aa7781040b17ca27fdd4f2ce6a9

Size: 96 KB.

![Fig. 03: AttackCapture™ showing IP 23.27.140[.]49 open directory data on port 8080](https://public-hunt-static-blog-assets.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/12-2025/Inside+DPRK+Operations+New+Lazarus+and+Kimsuky+Infrastructure+Uncovered+Across+Global+Campaigns+figure+3.png) Fig. 03: AttackCapture™ showing IP 23.27.140[.]49 open directory data on port 8080

Fig. 03: AttackCapture™ showing IP 23.27.140[.]49 open directory data on port 8080Upon analysis, the ELF exhibits similar behavior to the BADCALL backdoor that was previously seen in the 3CX supply chain attack by Lazarus. One of these, 23.27.177[.]183, appears in Hunt.io IP intelligence as Lazarus-linked infrastructure and has been observed in prior Lazarus campaigns.

![Fig. 04: Hunt.io IP intelligence data for 23.27.177[.]183](https://public-hunt-static-blog-assets.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/12-2025/Inside+DPRK+Operations+New+Lazarus+and+Kimsuky+Infrastructure+Uncovered+Across+Global+Campaigns+-+figure+4.png) Fig. 04: Hunt.io IP intelligence data for 23.27.177[.]183

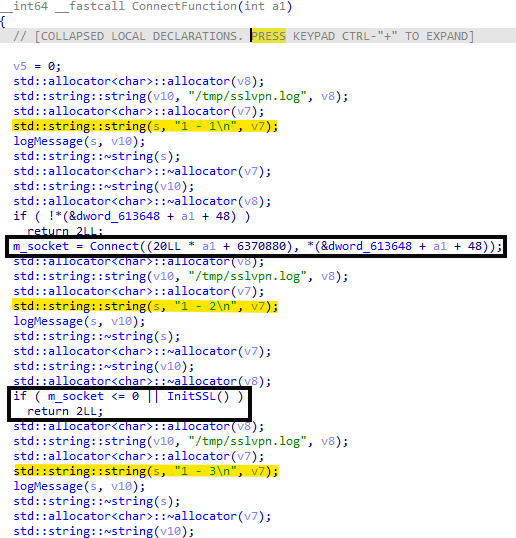

Fig. 04: Hunt.io IP intelligence data for 23.27.177[.]183Analysis of New Linux Variant of Badcall Backdoor

The Badcall backdoor has been one of the recognizable malware associated with Lazarus-linked operations. It played a visible part in several of their campaigns over the years, including the 2023 3CX supply-chain attack, where the first Linux version of Badcall was deployed as part of the post-exploitation chain.

This new Linux variant of BADCALL was found being hosted on 23.27.140[.]49. We analyzed the sample and found a small but important update in this variant.

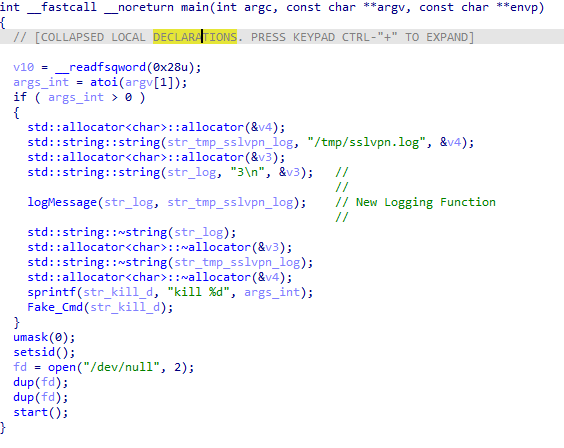

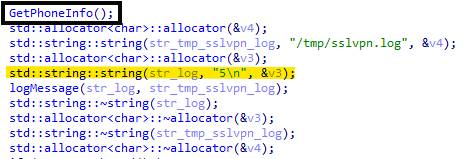

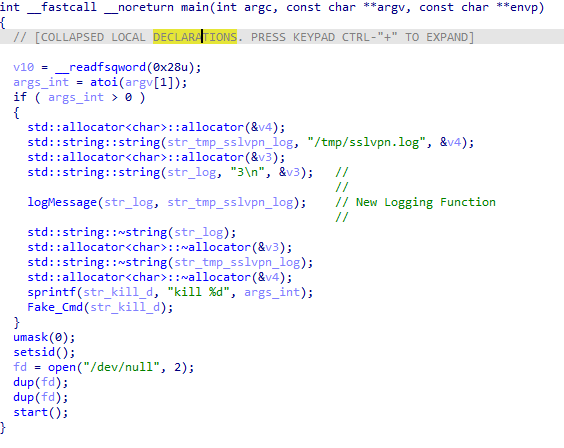

Fig. 05: New Linux Variant of Badcall Backdoor, Main Function

Fig. 05: New Linux Variant of Badcall Backdoor, Main FunctionSimilar to the previous variant of Badcall, the first part of the program checks for a command-line argument, simulates a "kill" command passing the integer specified by the argument as process ID with the Fake_Cmd() function, and proceeds to daemonize itself and start its main operation.

The main difference in this variant is the addition of a log file in the /tmp/ directory named "sslvpn.log". This gives the operators a way to track Badcall's operations using the log file.

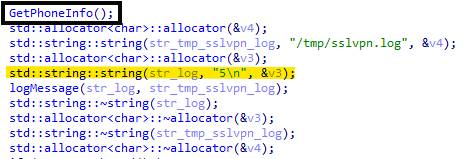

Fig. 06: Badcall logMessage() Function

Fig. 06: Badcall logMessage() FunctionThe

logMessage() function writes a timestamped entry into the log file by getting the current local time and writes it in

[YYYY-MM-DD HH:MM:SS] <message> format.

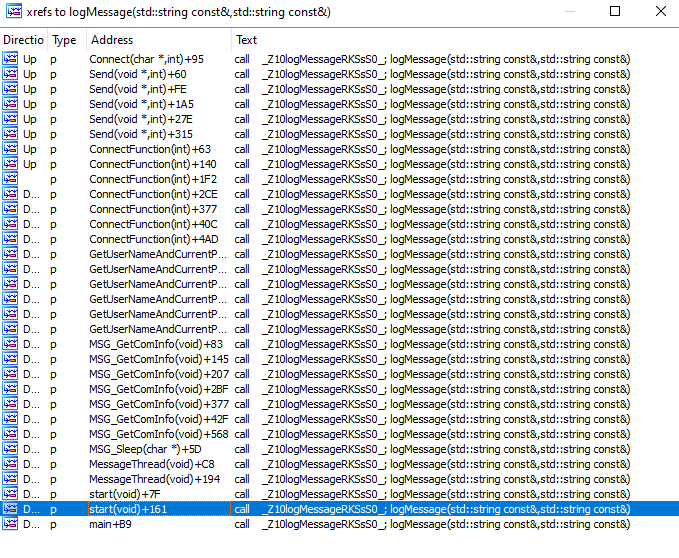

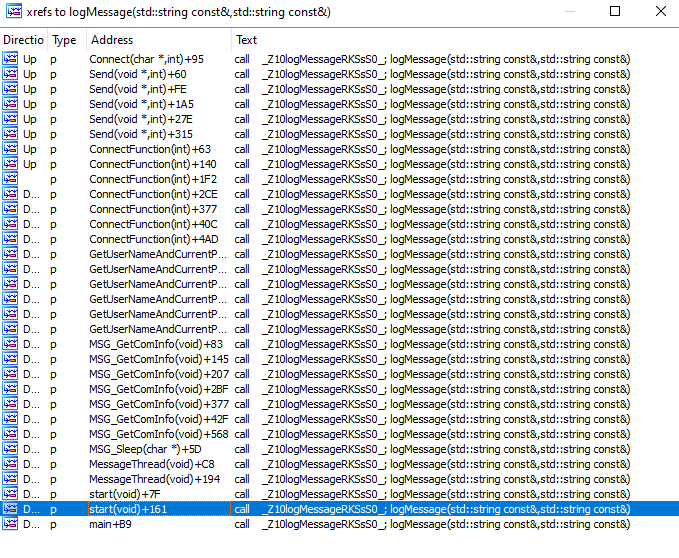

Fig. 07: Xref list of logMessage() function

Fig. 07: Xref list of logMessage() functionThe figure above shows a screenshot of all cross-references from other functions to the logMessage function. This highlights that Badcall now logs its activity across different malware routines.

Fig. 08: Sample logMessage() calls and log entries

Fig. 08: Sample logMessage() calls and log entriesAs seen in the screenshot above, the log entries are short numeric codes that change depending on the operation being done by the malware. This helps the attacker confirm that the malware is running properly and allows them to monitor its behavior throughout the intrusion.

From an operational standpoint, the development of this new Linux variant indicates Lazarus is continuously improving Badcall to better support upcoming operations. Even a small functional update like this can indicate an effort to improve operational efficiency and update their malware arsenal.

Hunt #2 - Lazarus DeceptiveDevelopment Cluster: Credential-Theft Toolkits in Open Directories

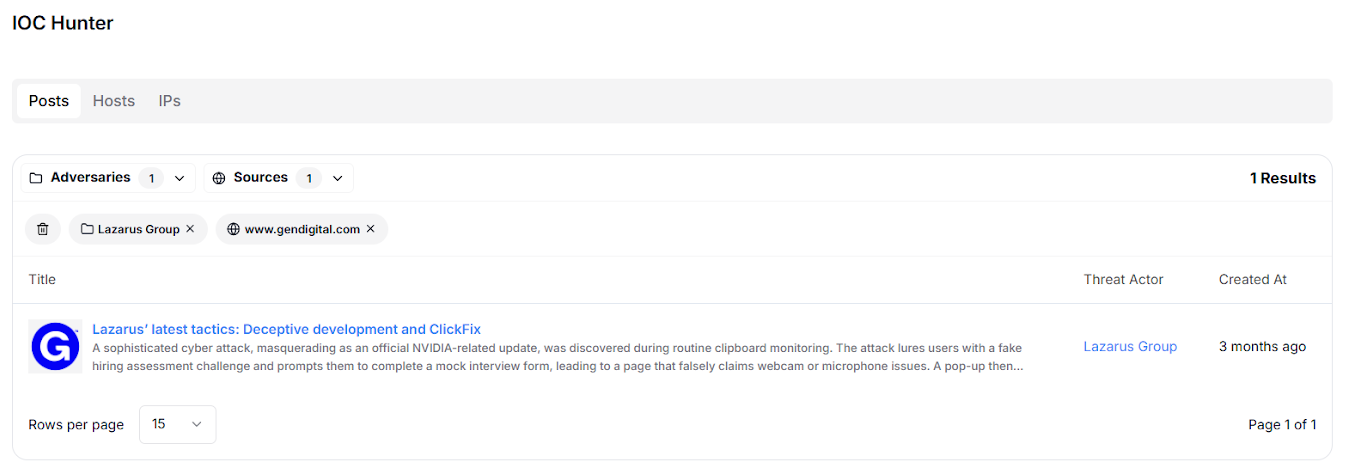

While some of the exposed infrastructure dates back to earlier campaigns, its reuse and recurring toolsets remain relevant for understanding current DPRK operational workflows. Recent analysis on the DeceptiveDevelopment campaign revealed a sophisticated Lazarus Group attack disguised as an NVIDIA-themed hiring assessment update. Using the hashes provided in the report as a starting point, we extracted two SHA-256 IoCs of credential-recovery utilities, "MailPassView" and "WebBrowserPassView", both used by the Lazarus group for credential harvesting.

Pivoting over these hashes in Hunt.io AttackCapture™ exposed open directories hosting these tools

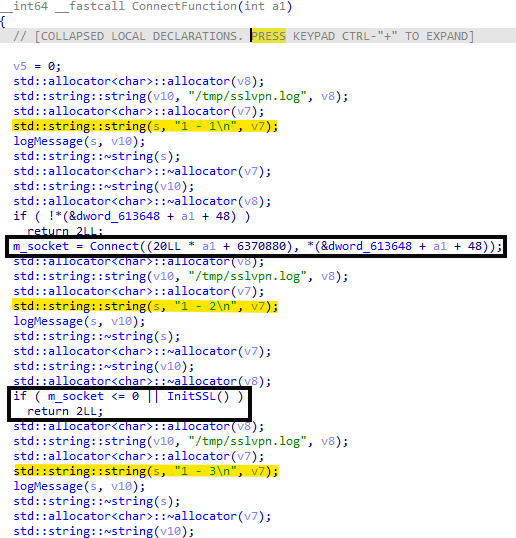

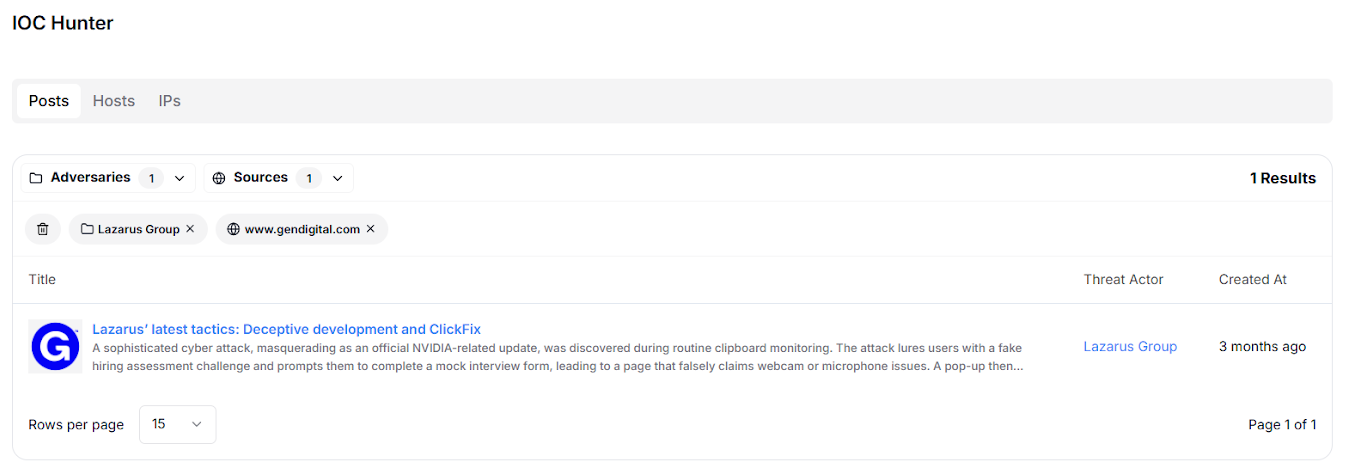

Fig. 09: IOC Hunter showing Lazarus group threat actor data

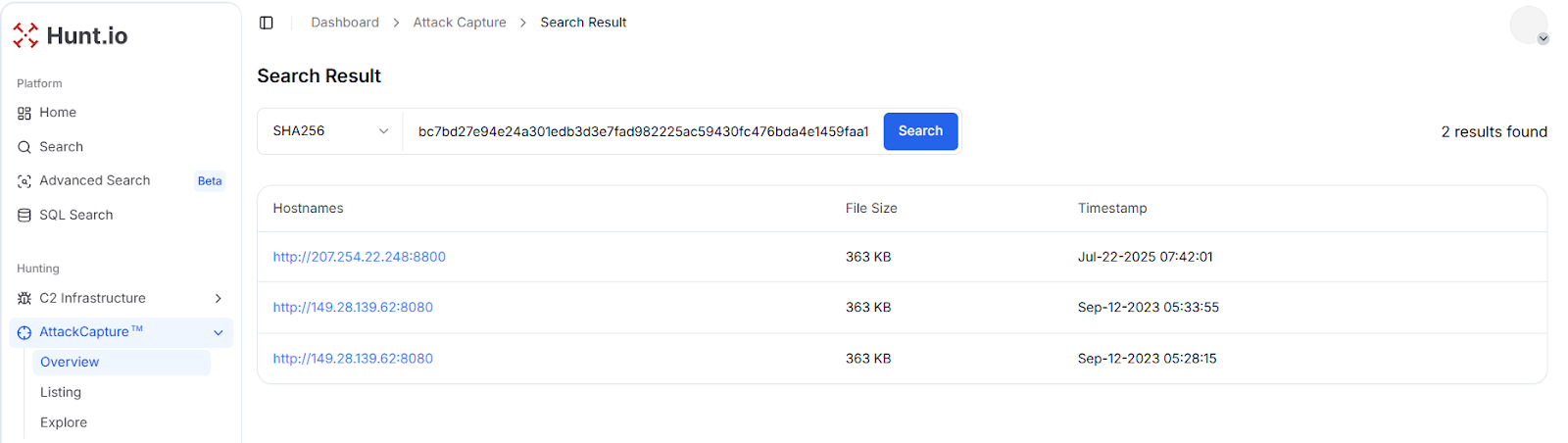

Fig. 09: IOC Hunter showing Lazarus group threat actor dataThe first pivot over MailPassView hash (bc7bd27e94e24a301edb3d3e7fad982225ac59430fc476bda4e1459faa1c1647) in Hunt.io revealed two open directories located at:

| Host | Size | Timestamp |

|---|---|---|

| http://207.254.22[.]248:8800 | 363 KB | - |

| http://149.28.139[.]62:8080 | 363 KB | Sep-12-2023 |

Fig. 10: AttackCapture™ search results for the SHA256 bc7bd27e94e24a301edb3d3e7fad982225ac59430fc476bda4e1459faa1c1647

Fig. 10: AttackCapture™ search results for the SHA256 bc7bd27e94e24a301edb3d3e7fad982225ac59430fc476bda4e1459faa1c1647Analysis for 207.254.22[.]248:8800

This directory, exposed at 207.254.22[.]248:8800, was serving a large credential-theft toolkit, containing 21 files organized into 2 subdirectories, totaling 112 MB. The toolset includes password recovery utilities and extraction tools (MailPassView, PasswordFox, ChromePass.exe, WebBrowserPassView, NetPass, MSPass.exe, Dialupass, PstPassword, IEPV), Large data exfiltration and profile-parsing utilities (hack-browser-data), and a data transfer tool (rclone binaries).

![Fig. 11: AttackCapture™ data 207.254.22[.]248:8800](https://public-hunt-static-blog-assets.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/12-2025/Inside%2BDPRK%2BOperations%2BNew%2BLazarus%2Band%2BKimsuky%2BInfrastructure%2BUncovered%2BAcross%2BGlobal%2BCampaigns%2B-%2Bfigure%2B11.png.png) Fig. 11: AttackCapture™ data 207.254.22[.]248:8800

Fig. 11: AttackCapture™ data 207.254.22[.]248:8800Analysis for host 207.254.22[.]248 shows the IP Address operating under AS30377 (MacStadium, Inc.) in Dublin, Ireland. Hunt.io's intelligence reports it as a Mythic C2 server on port 7443 in August 2025, and the IP has a recorded historical malicious open directory in July 2025, corresponding to the same directory referenced earlier, indicating the infrastructure has been repeatedly used in malicious activities.

![Fig. 12: Hunt.io's intelligence reporting IP 207.254.22[.]248 running a Mythic C2 server on port 7443](https://public-hunt-static-blog-assets.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/12-2025/Inside+DPRK+Operations+New+Lazarus+and+Kimsuky+Infrastructure+Uncovered+Across+Global+Campaigns+-+figure+12.png) Fig. 12: Hunt.io's intelligence reporting IP 207.254.22[.]248 running a Mythic C2 server on port 7443

Fig. 12: Hunt.io's intelligence reporting IP 207.254.22[.]248 running a Mythic C2 server on port 7443Analysis for 149.28.139[.]62:8080

This open directory node hosted at 149.28.139[.]62:8080, exposed a much larger toolkit, consisting of 201 total files, 42 subdirectories, and over 270 MB of content. The files include a Quasar RAT infrastructure (Quasar.exe, Quasar.Common.dll, quasar.p12, profiles, clients, config files), Credential harvesting tools (mailpv.exe, cli.exe, client.bin, multiple DLLs), and File-transfer and persistence utilities (pscp.exe, protobuf-net.dll, etc).

![Fig. 13: Directory view of 149.28.139[.]62:8080 exposing Quasar RAT tooling](https://public-hunt-static-blog-assets.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/12-2025/Inside%2BDPRK%2BOperations%2BNew%2BLazarus%2Band%2BKimsuky%2BInfrastructure%2BUncovered%2BAcross%2BGlobal%2BCampaigns%2B-%2Bfigure%2B13.png) Fig. 13: Directory view of 149.28.139[.]62:8080 exposing Quasar RAT tooling

Fig. 13: Directory view of 149.28.139[.]62:8080 exposing Quasar RAT toolingAnalysis for host 149.28.139[.]62 shows the IP Address is hosted under AS20473 (The Constant Company, LLC / Vultr) in Singapore. Our platform identifies a distinctive Quasar RAT on port 1888 documented between September and October 2023.

![Fig. 14: Hunt.io intelligence showing Quasar RAT activity on 149.28.139[.]62](https://public-hunt-static-blog-assets.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/12-2025/Inside+DPRK+Operations+New+Lazarus+and+Kimsuky+Infrastructure+Uncovered+Across+Global+Campaigns+-+figure+14.png) Fig. 14: Hunt.io intelligence showing Quasar RAT activity on 149.28.139[.]62

Fig. 14: Hunt.io intelligence showing Quasar RAT activity on 149.28.139[.]62Both investigated infrastructure nodes demonstrate clear indicators of malicious behavior. The first host (207.254.22[.]248) shows active 2025 usage, Mythic exposure, and a broad credential-exfiltration suite matching contemporary Lazarus TTPs. The second host (149.28.139[.]62) represents older but relevant infrastructure, containing extensive Quasar RAT tooling and supporting binaries consistent with Lazarus' earlier-stage operations.

Across both servers, the repeated presence of MailPassView, browser credential extractors, and exfiltration utilities demonstrates a persistent DPRK pattern of using open directories as tool staging nodes, enabling rapid deployment during intrusions while maintaining minimal operational friction.

It is important to note that tools such as MailPassView and WebBrowserPassView are legitimate, publicly available utilities and are used by a wide range of threat actors. Their presence alone is not sufficient for attribution. In this case, their relevance comes from their co-location with infrastructure previously linked to Lazarus activity, including historical C2 exposure, repeated reuse of the same hosts, and overlap with known DPRK tradecraft observed in adjacent campaigns.

The pivot over the second hash (36541fad68e79cdedb965b1afcdc45385646611aa72903ddbe9d4d064d7bffb9) reveals two exposed open directories on Hunt.io. The first directory "207.254.22[.]248:8800" is already known from prior tracking and contains a large Quasar RAT operator environment, consistent with previously observed DPRK tradecraft.

![Fig. 15: AttackCapture™ directory listing for 154.216.177[.]215](https://public-hunt-static-blog-assets.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/12-2025/Inside+DPRK+Operations+New+Lazarus+and+Kimsuky+Infrastructure+Uncovered+Across+Global+Campaigns+-+figure+15.png) Fig. 15: AttackCapture™ directory listing for 154.216.177[.]215

Fig. 15: AttackCapture™ directory listing for 154.216.177[.]215Analysis for 154.216.177.215

The host "154.216.177[.]215", operating under AS135377 (LARUS Limited) in Hong Kong, exposes an exceptionally large and sensitive open directory containing 10,731 files, 1,222 subdirectories, and nearly 2 GB of operational data. The files include offensive security tooling (sqlmap, masscan, nmap, hping, tcpdump, ngrok, gost, microsocks, frpc/frps, impacket) and Nuclei (7,820 templates), alongside browser password-stealers, privilege-escalation binaries, packet capture tools, RDP configs, and multiple Python environments.

The presence of development artifacts, Burp Suite keygen links, Privoxy configs, Mimikatz folder stubs, and raw camera-roll/screenshot directories suggests the machine may represent either a compromised Windows workstation or an operator-controlled staging environment repurposed for tooling and development.

The IoC-linked WebBrowserPassView.exe (421 KB) found here aligns directly with the Lazarus DeceptiveDevelopment cluster, and the breadth of tools combined with personal artifacts, logs, and credential-extraction utilities illustrates an active threat actor operations hub, likely used for reconnaissance, credential theft, LPE testing, and offensive development workflows.

![Fig. 16: AttackCapture™ open directory view for 154.216.177[.]215](https://public-hunt-static-blog-assets.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/12-2025/Inside+DPRK+Operations+New+Lazarus+and+Kimsuky+Infrastructure+Uncovered+Across+Global+Campaigns+-+figure+16.png) Fig. 16: AttackCapture™ open directory view for 154.216.177[.]215

Fig. 16: AttackCapture™ open directory view for 154.216.177[.]215Once the pivots move from payloads to infrastructure, the separation between DPRK subgroups becomes less distinct and shared operational habits start to surface.

Hunt #3 - Lazarus FRP Infrastructure Hunt - 3CX Supply Chain Linkage

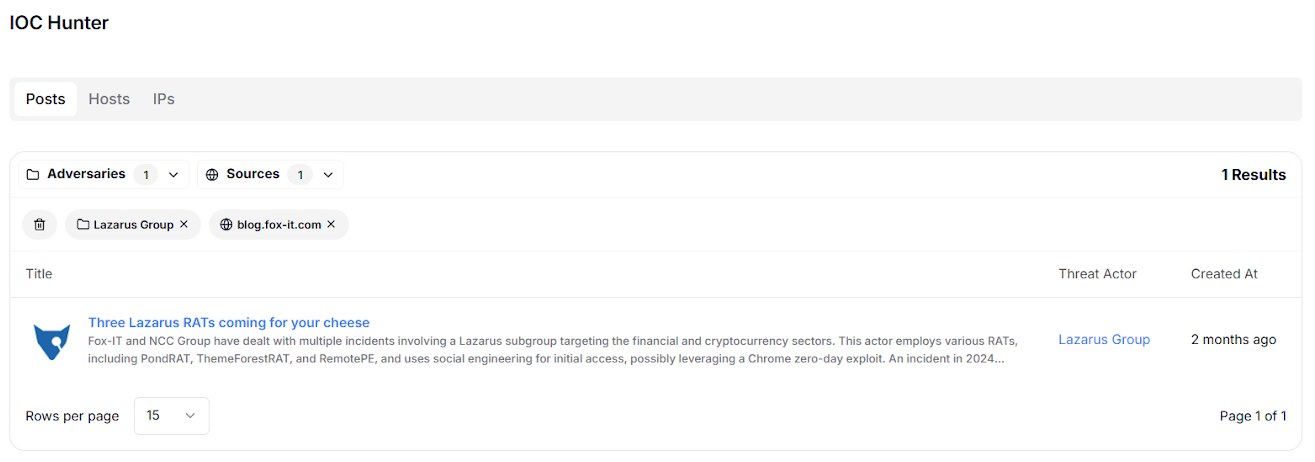

From IOC Hunter, we picked up another article titled "Three Lazarus RATs coming for your cheese", which highlights the use of Fast Reverse Proxy (FRP) within DPRK-linked APT campaigns.

This directly aligns with earlier findings from 2023, when Google Cloud's threat intelligence team analyzed the 3CX software supply-chain compromise and discovered that the Lazarus Group had incorporated FRP components into their multi-stage intrusion chain.

Across DPRK-linked intrusions, FRP usually sits between the compromised host and the operator, giving Lazarus a dependable way to maintain access even when outbound traffic is filtered or restricted.

FRP itself is an open-source tunneling framework and is widely used across many threat ecosystems, including multiple Chinese APT groups. Its use here is not treated as a unique Lazarus indicator. Instead, the attribution signal comes from the consistent deployment pattern observed across multiple VPS nodes, identical binaries served on the same port, and its alignment with infrastructure previously tied to Lazarus operations, including those documented during the 3CX incident.

While FRP is typically deployed internally within victim environments, its repeated exposure as internet-facing infrastructure in this cluster represents an operational choice that differs from benign usage patterns.

In that incident, the attack began with a trojanized 3CX desktop client and progressed through several stages of compromise, marking one of the earliest publicly observed uses of FRP by Lazarus. Together, these insights reinforce the group's continued reliance on FRP tooling across different campaigns and timelines.

Fig. 17: IOC Hunter entry for the FRP-related Lazarus campaign

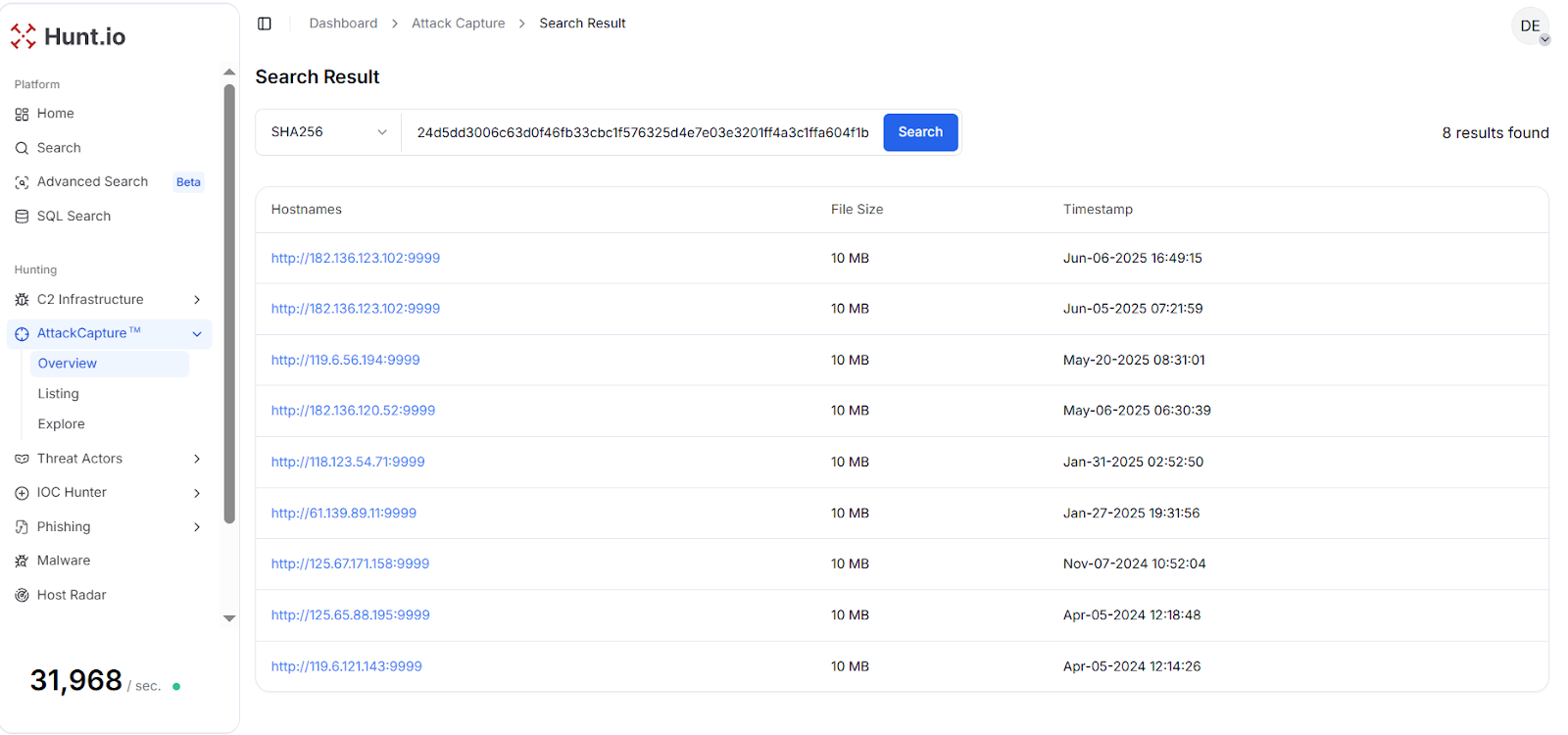

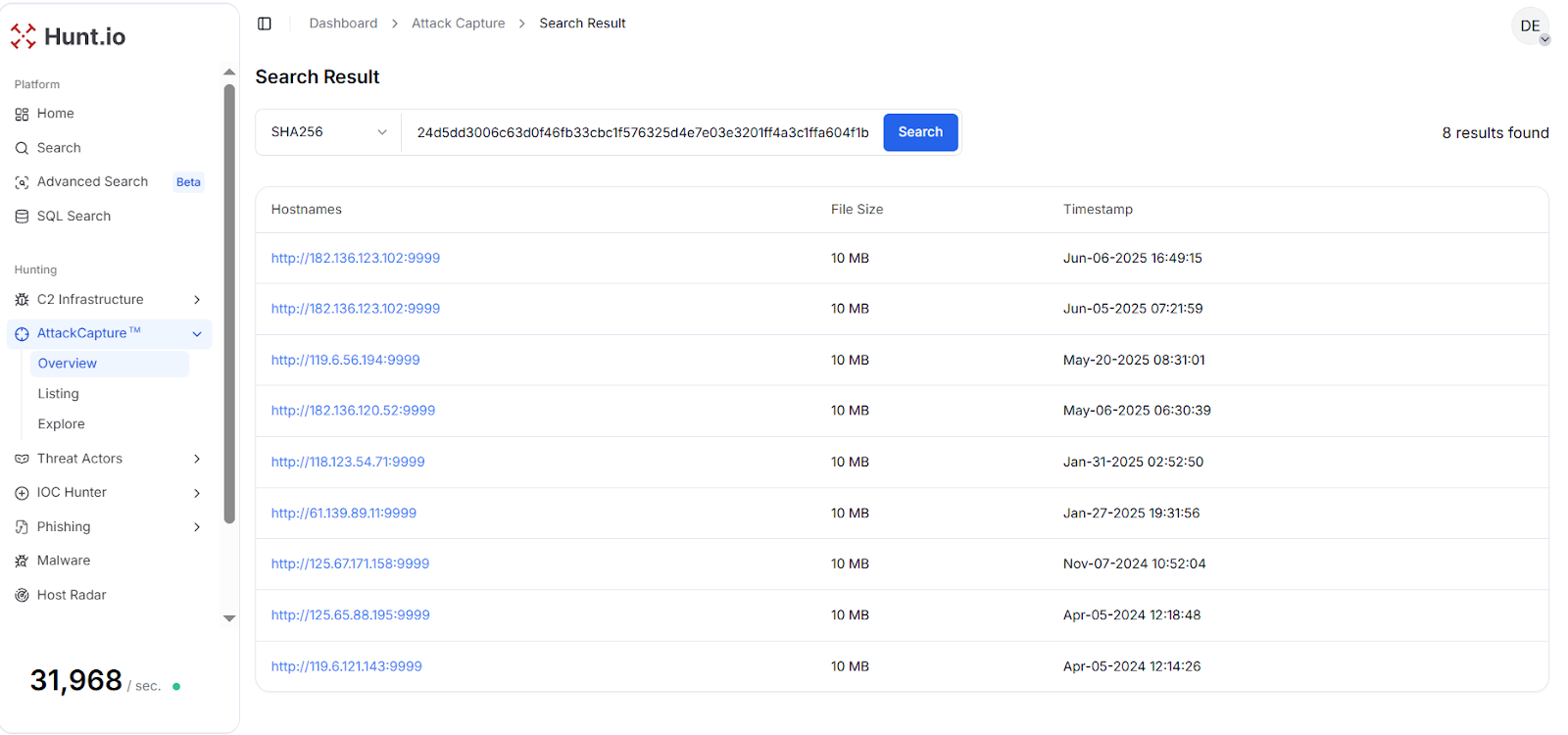

Fig. 17: IOC Hunter entry for the FRP-related Lazarus campaignPivoting on the FRP hash 24d5dd3006c63d0f46fb33cbc1f576325d4e7e03e3201ff4a3c1ffa604f1b74a, Our platform surfaced eight hosting instances (182.136.123[.]102, 119.6.56[.]194, 182.136.120[.]52, 118.123.54[.]71, 61.139.89[.]11, 125.67.171[.]158, 125.65.88[.]195, and 119.6.121[.]143) over the same port "9999".

Fig. 18: AttackCapture™ results for FRP hash 24d5dd3006c63d0f46fb33cbc1f576325d4e7e03e3201ff4a3c1ffa604f1b74a

Fig. 18: AttackCapture™ results for FRP hash 24d5dd3006c63d0f46fb33cbc1f576325d4e7e03e3201ff4a3c1ffa604f1b74aThe uniformity across these nodes is notable. All eight servers returned the same FRP binary, with identical file size and configuration patterns. This consistency suggests that the operators are provisioning these nodes in a scripted or automated way, rather than configuring each server manually.

Each node served a 10 MB FRP binary, indicating widespread deployment of identical tunneling infrastructure likely used to proxy internal footholds back to operator-controlled servers.

This pattern strongly aligns with Lazarus Group's operational practice of deploying uniform FRP instances across rotating Chinese and APAC-region VPS hosts to support covert C2 communications in extended campaigns. FRP gives the operators a stable way to maintain access even when more traditional C2 channels are blocked or sinkholed.

The concentration of these nodes on regional VPS providers, mostly within the same geographic footprint, matches earlier Lazarus clusters that relied on inexpensive and short-lived infrastructure. Running multiple identical FRP nodes in parallel also hints at simultaneous operations or at a rotating pool of redirectors used to support different intrusion paths.

Hunt #4 - Pivoting Into APT Lazarus Certificate

The hunt began by selecting the domain secondshop[.]store from Hunt.io's IOC Hunter using the Lazarus Group filter.

![Fig. 19: IOC Hunter showing secondshop[.]store linked to Lazarus Group](https://public-hunt-static-blog-assets.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/12-2025/Inside+DPRK+Operations+New+Lazarus+and+Kimsuky+Infrastructure+Uncovered+Across+Global+Campaigns+-+figure+19.png) Fig. 19: IOC Hunter showing secondshop[.]store linked to Lazarus Group

Fig. 19: IOC Hunter showing secondshop[.]store linked to Lazarus GroupThe domain resolved to the IP Address "23.254.128[.]114" which is the part of AS54290 (Hostwinds LLC.). According to our data, the IP carried a High-Risk reputation with explicit labeling as Lazarus Group, and exhibited historical TLS/HTTP activity on port 443, consistent with typical Lazarus infrastructure patterns.

![Fig. 20: Hunt.io IP intelligence for 23.254.128[.]114](https://public-hunt-static-blog-assets.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/12-2025/Inside+DPRK+Operations+New+Lazarus+and+Kimsuky+Infrastructure+Uncovered+Across+Global+Campaigns+-+figure+20.png) Fig. 20: Hunt.io IP intelligence for 23.254.128[.]114

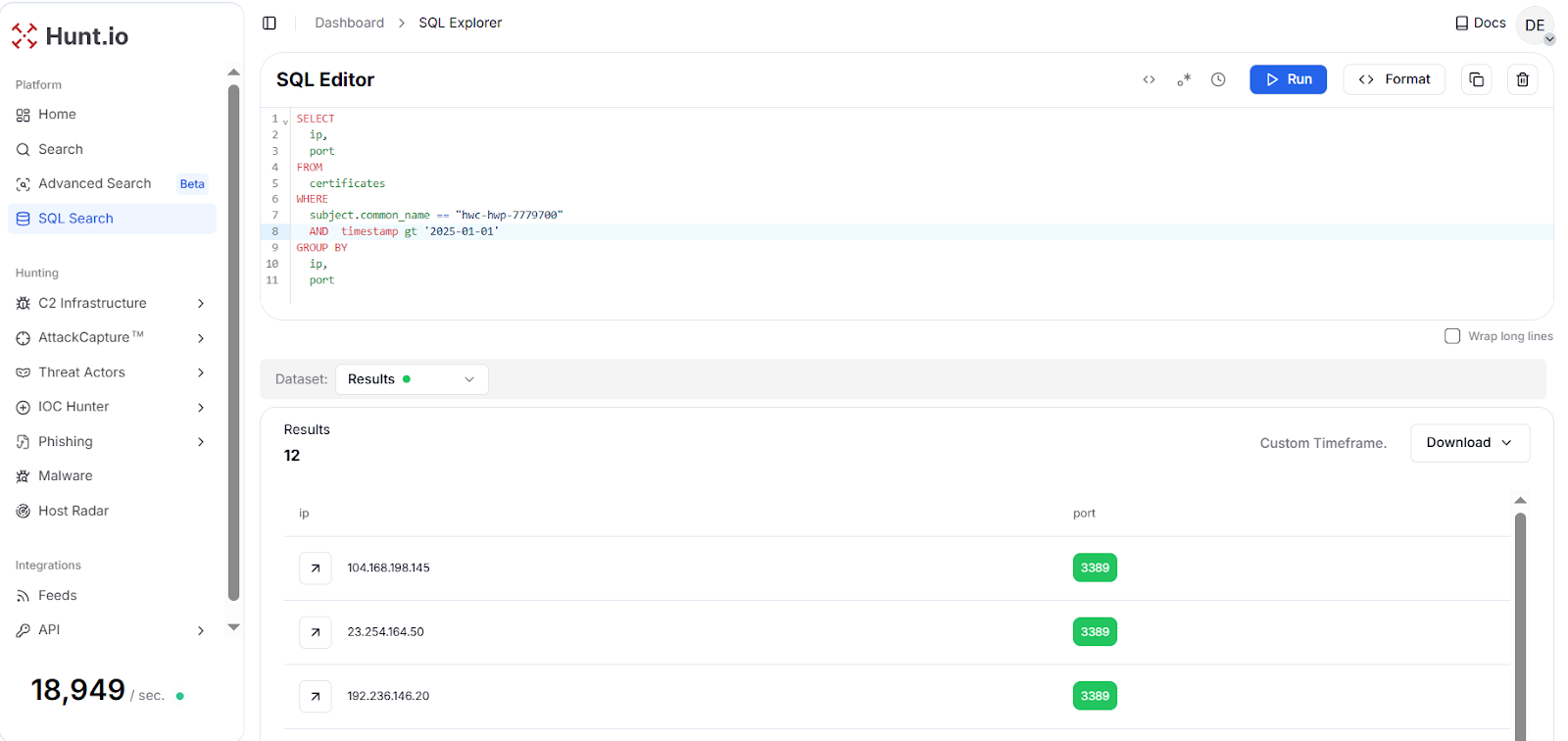

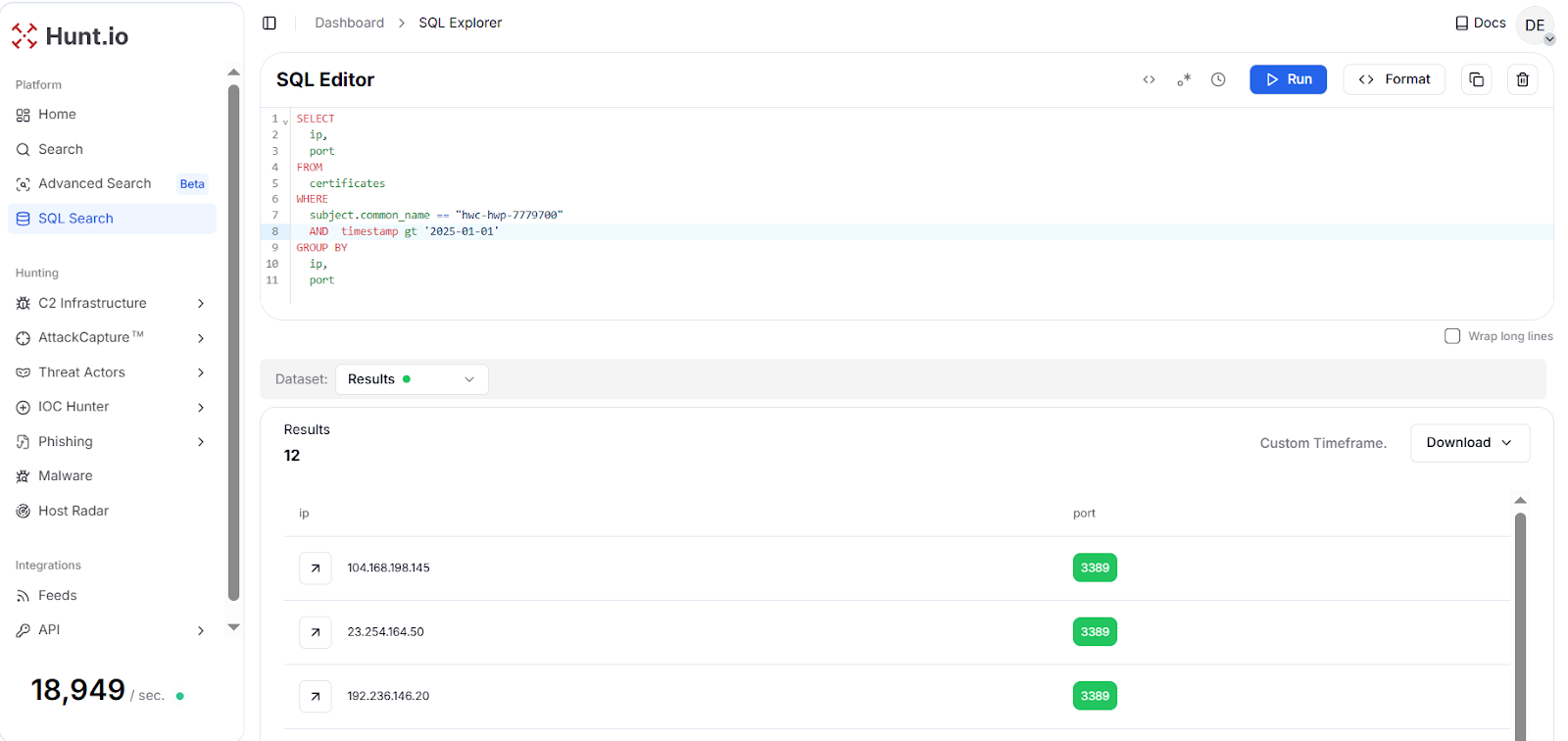

Fig. 20: Hunt.io IP intelligence for 23.254.128[.]114To widen the view beyond a single domain, we pivoted from the certificate associated with the IP using the field subject.common_name == "hwc-hwp-7779700" using HuntSQL query. The result shows 12 IP Addresses all exposed with port 3389 since January 2025.

SELECT

ip,

port

FROM

certificates

WHERE

subject.common_name == "hwc-hwp-7779700"

AND timestamp gt '2025-01-01'

GROUP BY

ip,

port

CopyExample output:

Fig. 21: HuntSQL results showing 12 IPs tied to certificate subject "hwc-hwp-7779700"

Fig. 21: HuntSQL results showing 12 IPs tied to certificate subject "hwc-hwp-7779700"The consistent exposure of RDP across these hosts suggests they are not passive servers but systems intended for operator access or staging. This behavior aligns with earlier Lazarus infrastructure, where exposed RDP has repeatedly been used for operator logins and hands-on management of distributed C2 nodes.

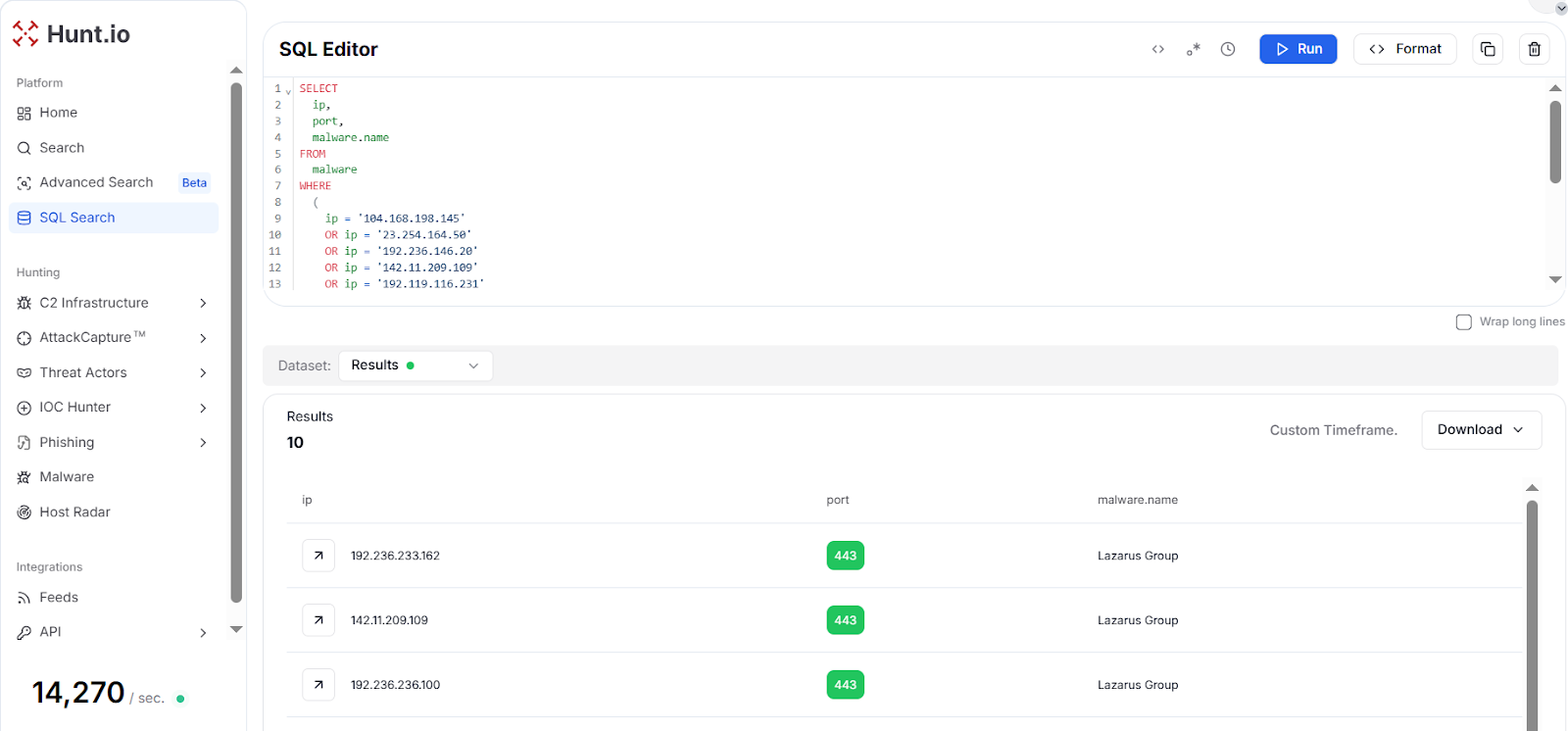

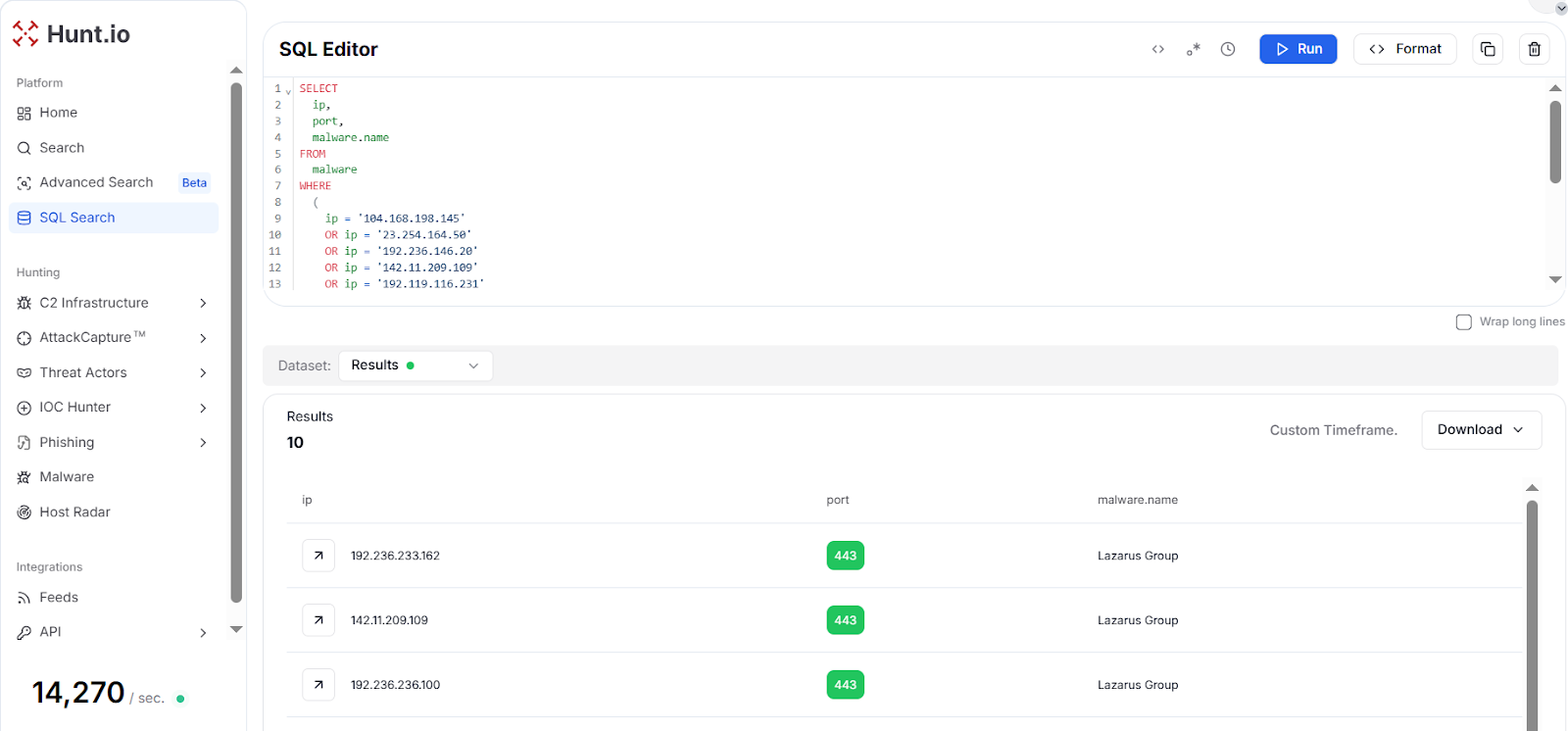

To validate whether these IPs were linked to actual malicious operations, we queried our Hunt.io malware database for all 12 IP addresses. The results show that ten of the queried IPs were directly associated with "Lazarus Group" malware on port 443, confirming active operational infrastructure.

SELECT

ip,

port,

malware.name

FROM

malware

WHERE

(

ip = '104.168.198.145'

OR ip = '23.254.164.50'

OR ip = '192.236.146.20'

OR ip = '142.11.209.109'

OR ip = '192.119.116.231'

OR ip = '192.236.233.162'

OR ip = '192.236.176.164'

OR ip = '192.236.236.100'

OR ip = '192.236.146.22'

OR ip = '23.254.128.114'

OR ip = '192.236.233.165'

OR ip = '104.168.151.116'

)

AND timestamp gt '2025-01-01'

GROUP BY

ip,

port,

malware.name

CopyOutput example:

Fig. 22: Malware dataset results correlating 10 of 12 certificate-linked IPs to Lazarus samples

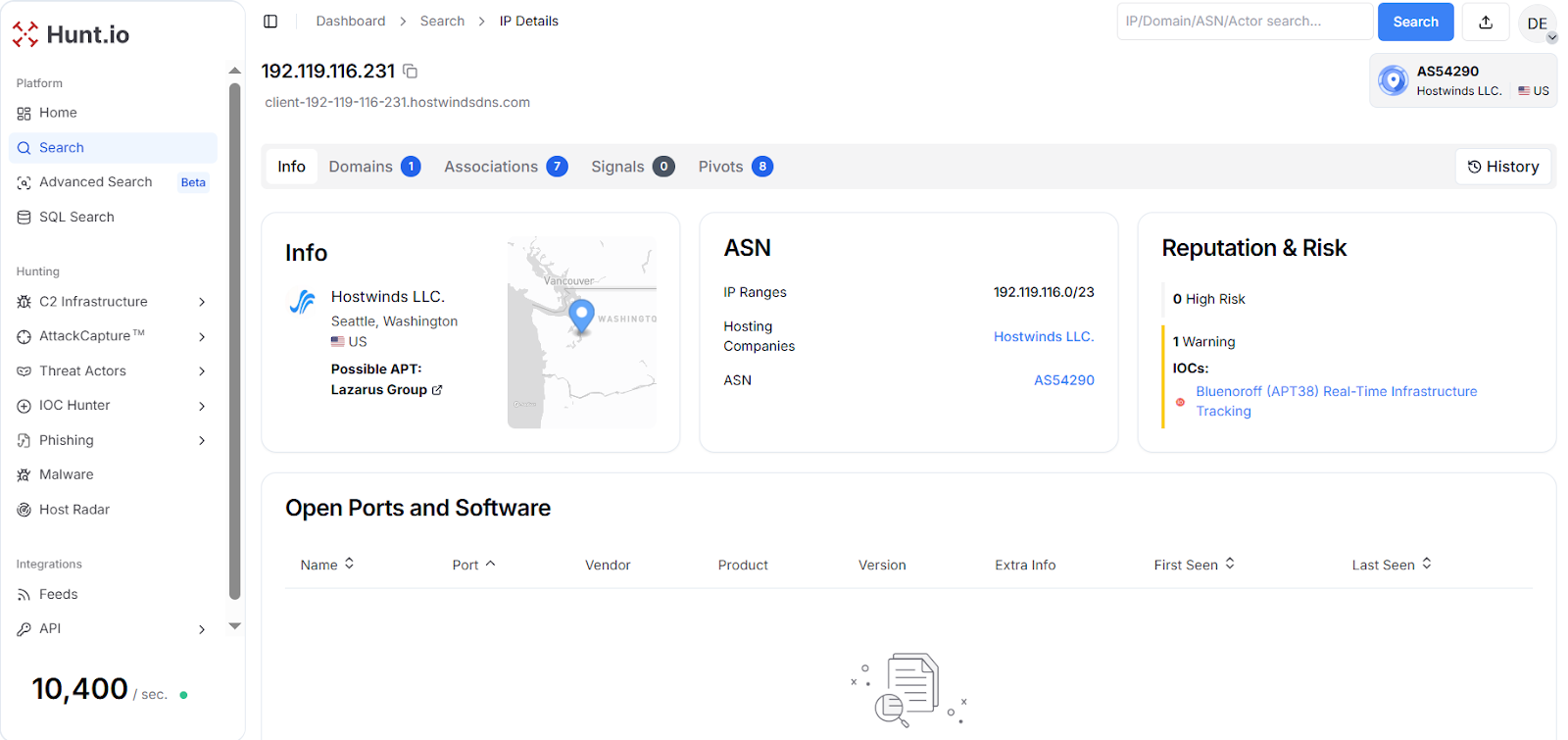

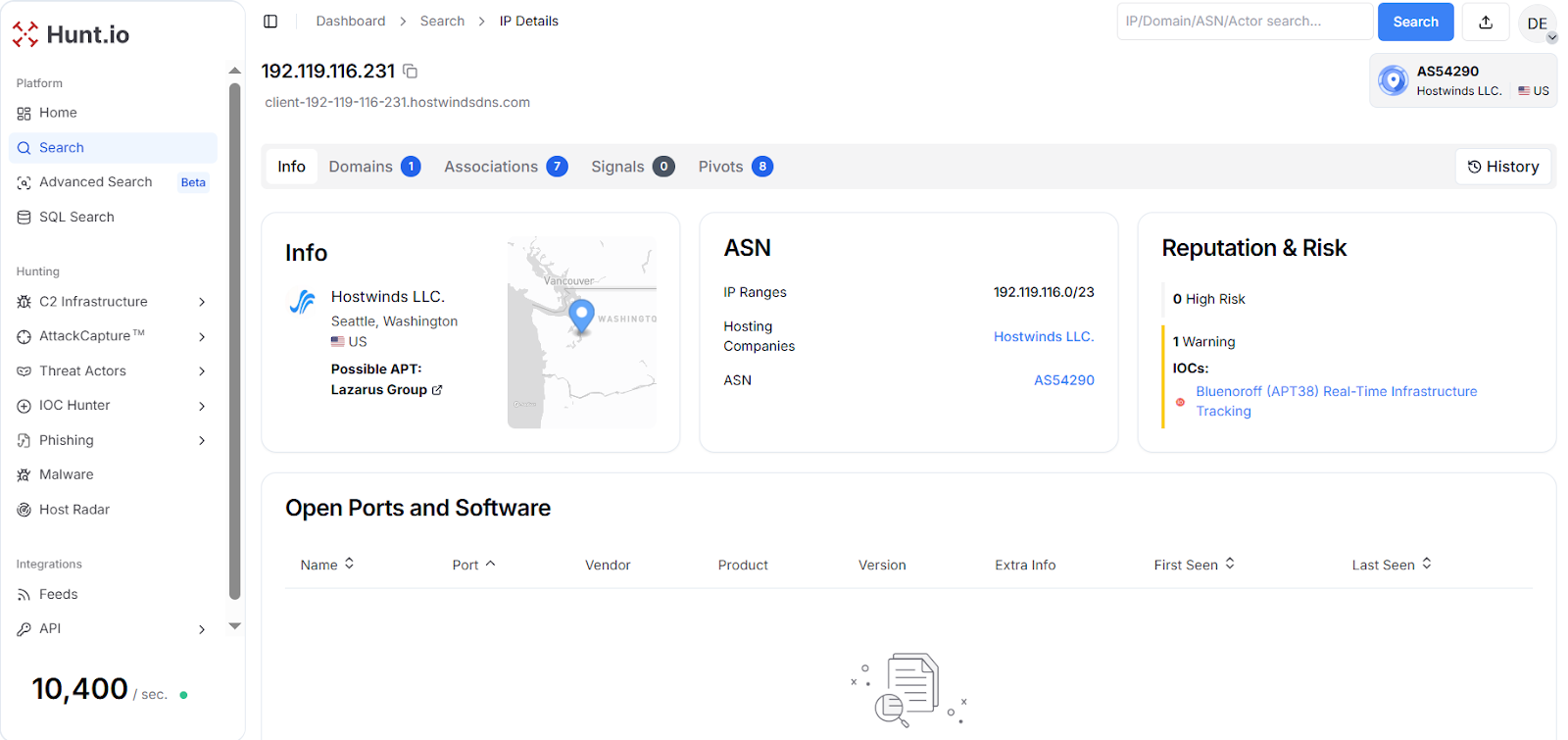

Fig. 22: Malware dataset results correlating 10 of 12 certificate-linked IPs to Lazarus samplesThe remaining two IP addresses, 104.168.151[.]116 and 192.119.116[.]231, were manually enriched using Hunt.io's asset intelligence. Both belonged to Hostwinds' Seattle infrastructure with multiple pivots linking them to Bluenoroff (APT38) tracking campaigns.

The overlap with Bluenoroff at this stage is meaningful. Even though Lazarus and Bluenoroff operate with different mission profiles, shared infrastructure elements like certificates or hosting providers often suggest where their operational workflows may intersect. These small overlaps act as early markers of broader DPRK ecosystems that remain active behind individual campaigns.

Fig. 23: Hostwinds infrastructure node with pivots into Bluenoroff-linked activity.

Fig. 23: Hostwinds infrastructure node with pivots into Bluenoroff-linked activity.![Fig. 24: Asset intelligence enrichment for 104.168.151[.]116](https://public-hunt-static-blog-assets.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/12-2025/Inside%2BDPRK%2BOperations%2BNew%2BLazarus%2Band%2BKimsuky%2BInfrastructure%2BUncovered%2BAcross%2BGlobal%2BCampaigns%2B-%2Bfigure%2B24.png) Fig. 24: Asset intelligence enrichment for 104.168.151[.]116

Fig. 24: Asset intelligence enrichment for 104.168.151[.]116The analysis confirms that the secondshop[.]store acts as an entry point into a much broader and still-active Lazarus ecosystem, revealing both mature C2 nodes and auxiliary proxy infrastructure.

These observations point to a few concrete signals defenders can use to stay ahead of this activity.

Defender and Hunting Guidance

The infrastructure uncovered across the four hunts highlights several reliable signals defenders can use to track DPRK activity, even when payloads or lures shift.

Open directory exposure

Multiple staging servers hosted credential theft tools, Quasar environments, Linux backdoors, rclone binaries, and offensive toolkits. These directories tend to recur across different nodes with almost identical layouts. Monitoring for exposed directories that contain these repeating toolsets can reveal new infrastructure tied to the same operators.

Repeated FRP deployments

The same FRP binary appeared across eight VPS hosts, all serving the same 10 MB file on the same port. This creates a predictable footprint that can be monitored across providers where DPRK operators tend to host infrastructure.

As with other open-source tooling, FRP should be evaluated in combination with deployment patterns, hosting context, and historical infrastructure reuse rather than treated as a standalone attribution signal.

Certificate reuse

The Lazarus-linked certificate that surfaced twelve IP addresses showed how certificate pivots can expose entire infrastructure clusters. Tracking newly exposed hosts that reuse the same certificate profile or appear on the same RDP or TLS ports can uncover new operational nodes before they are used in active campaigns.

Historical telemetry on shared VPS providers

Throughout the hunts, the same hosting providers reappeared in different campaigns. Watching for recurring combinations of provider, certificate profile, port exposure, and FRP artifacts can help surface new infrastructure even before malware begins communicating with it.

These signals help defenders move from reactive identification of DPRK activity to a more proactive view of how the operators prepare and maintain their infrastructure.

Conclusion

Across all four hunts, the same operational habits kept surfacing. The FRP nodes deployed in identical configurations, the recurring credential-theft toolkits exposed in open directories, and the reuse of certificates and VPS providers all point back to a tightly patterned workflow inside the broader DPRK ecosystem. These stable behaviors make their infrastructure easier to track than the shifting payloads or lures used in individual campaigns.

For defenders, the signals that consistently appeared in this investigation remain the most reliable: repeated FRP binaries on port 9999, credential harvesting kits staged on exposed HTTP directories, certificate subjects reused across clusters of RDP-enabled hosts, and infrastructure repeatedly provisioned through the same regional providers. Watching for these patterns gives teams an advance look into DPRK activity as it forms, not only after an intrusion is underway.

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)

The following list gathers all indicators surfaced during the hunts, including hashes, infrastructure nodes, and associated DPRK-linked assets.

| IOCs | Description |

|---|---|

| a3876a2492f3c069c0c2b2f155b4c420d8722aa7781040b17ca27fdd4f2ce6a9 | New Linux Variant of Badcall Backdoor |

| cc307cfb401d1ae616445e78b610ab72e1c7fb49b298ea003dd26ea80372089a | Old Linux Variant of Badcall Backdoor |

| a5350b1735190a9a275208193836432ed99c54c12c75ba6d7d4cb9838d2e2106 | Poolrat |

| ff32bc1c756d560d8a9815db458f438d63b1dcb7e9930ef5b8639a55fa7762c9 | Poolrat |

| 85045d9898d28c9cdc4ed0ca5d76eceb457d741c5ca84bb753dde1bea980b516 | Poolrat |

| bc7bd27e94e24a301edb3d3e7fad982225ac59430fc476bda4e1459faa1c1647 | MailPassView |

| 36541fad68e79cdedb965b1afcdc45385646611aa72903ddbe9d4d064d7bffb9 | WebBrowserPassView |

| 24d5dd3006c63d0f46fb33cbc1f576325d4e7e03e3201ff4a3c1ffa604f1b74a | FastReverseProxy |

| 23.27.140[.]49:8080 | Badcall Host URL |

| 23.27.177[.]183 | Badcall C2 server |

| 23.254.211[.]230 | Badcall C2 server |

| 207.254.22[.]248:8800 | Opendir |

| 149.28.139[.]62:8080 | Opendir |

| 154.216.177.215:8080 | Opendir |

| 182.136.123[.]102:9999 | FRP Host URL |

| 119.6.56[.]194:9999 | FRP Host URL |

| 182.136.120[.]52:9999 | FRP Host URL |

| 118.123.54[.]71:9999 | FRP Host URL |

| 61.139.89[.]11:9999 | FRP Host URL |

| 125.67.171[.]158:9999 | FRP Host URL |

| 125.65.88[.]195:9999 | FRP Host URL |

| 119.6.121[.]143:9999 | FRP Host URL |

| secondshop[.]store | Lazarus-linked pivot domain |

| 23.254.128[.]114 | Lazarus certificate-linked infrastructure |

| 104.168.198[.]145 | Lazarus certificate-linked infrastructure |

| 23.254.164[.]50 | Lazarus certificate-linked infrastructure |

| 192.236.146[.]20 | Lazarus certificate-linked infrastructure |

| 142.11.209[.]109 | Lazarus certificate-linked infrastructure |

| 192.236.233[.]162 | Lazarus certificate-linked infrastructure |

| 192.236.176[.]164 | Lazarus certificate-linked infrastructure |

| 192.236.236[.]100 | Lazarus certificate-linked infrastructure |

| 192.236.146[.]22 | Lazarus certificate-linked infrastructure |

| 192.236.233[.]165 | Lazarus certificate-linked infrastructure |

| 192.119.116[.]231 | Lazarus infrastructure with Bluenoroff overlap |

| 104.168.151[.]116 | Lazarus infrastructure with Bluenoroff overlap |

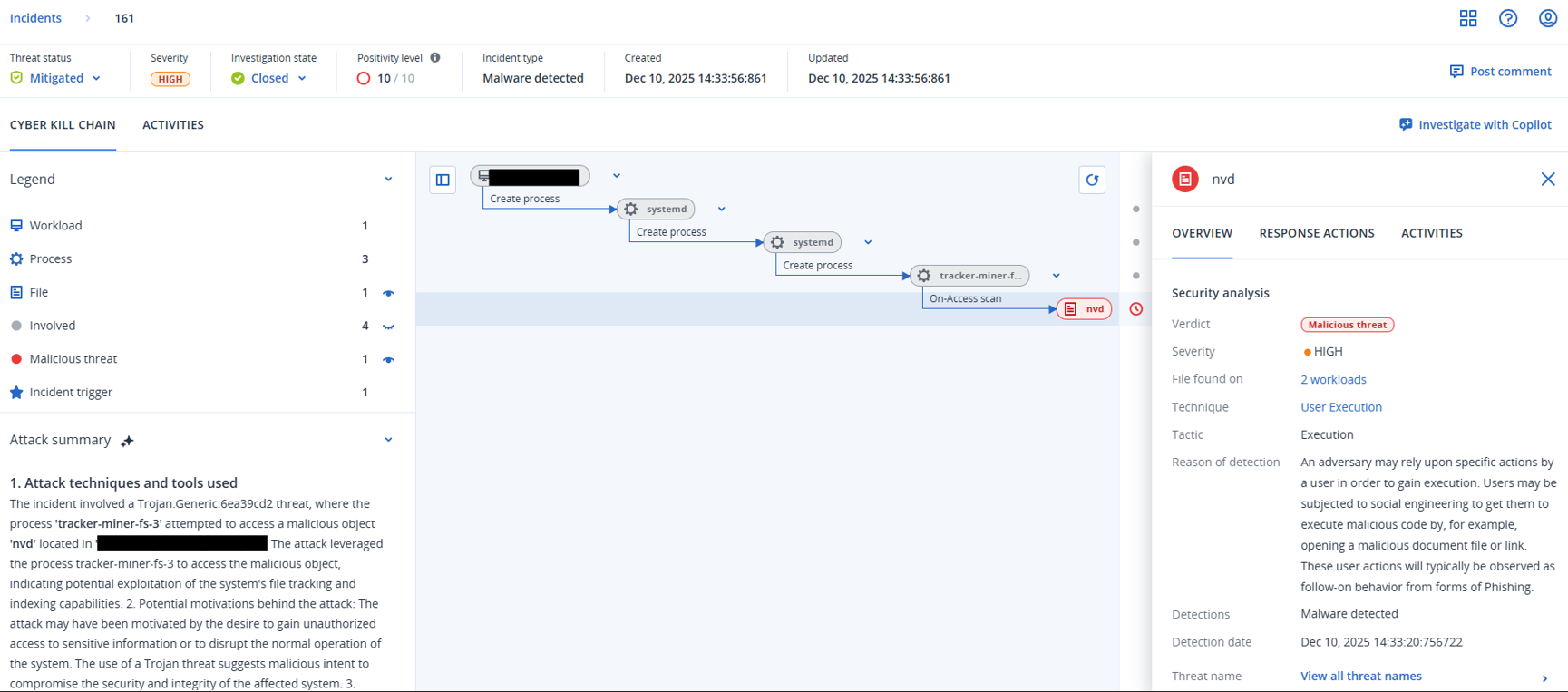

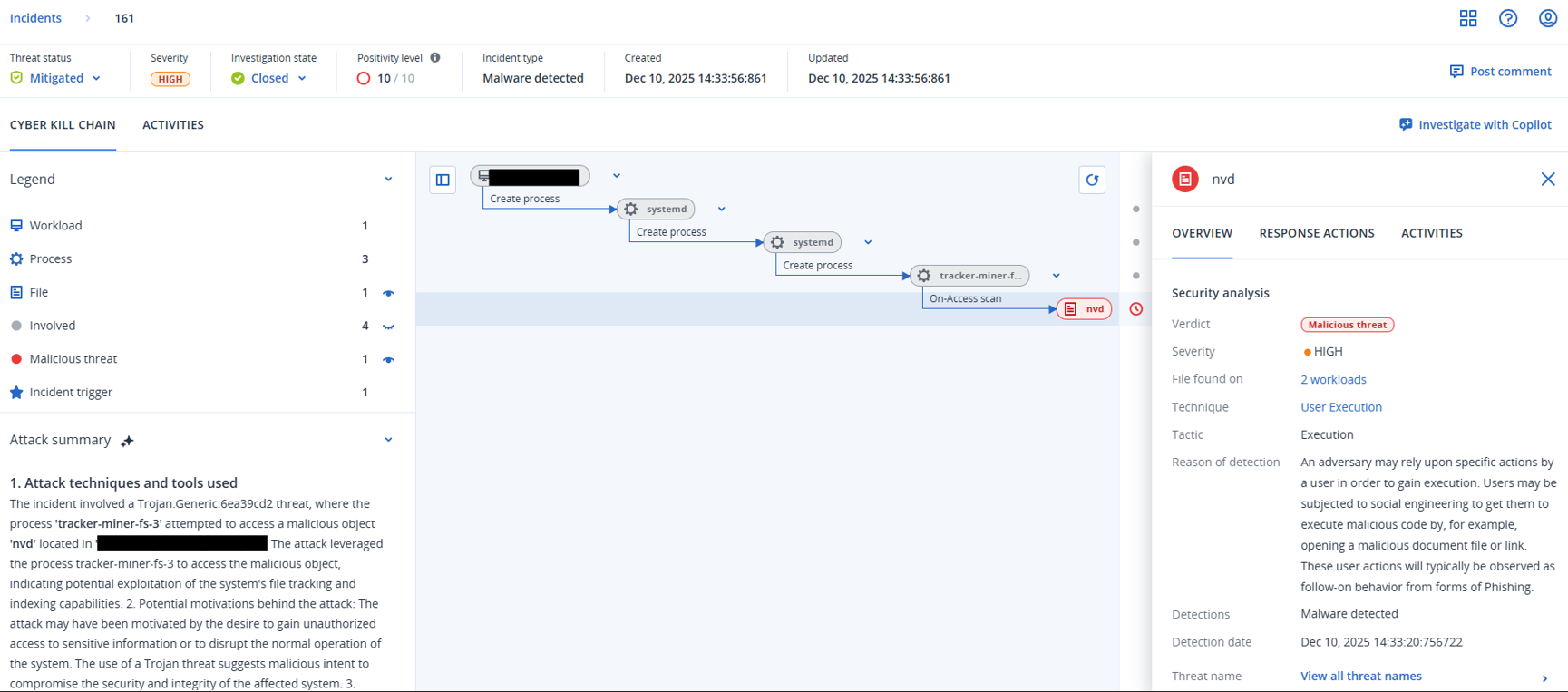

Detection by Acronis

As part of this joint work, the Acronis Threat Research Unit reviewed the activity described in this report from the endpoint perspective. Their EDR/XDR telemetry surfaced the same behaviors seen in the infrastructure layer, including the latest Badcall variant, credential harvesting tools, and several of the Lazarus-linked nodes highlighted above.

This gives an additional confirmation path: the infrastructure we observed being prepared and used by DPRK operators also appeared as endpoint-level detections inside Acronis' visibility. It reinforces the relationship between the external infrastructure pivots and the on-host activity defenders may see during similar intrusions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Daniel Gordon for his peer review and analytical feedback on tooling usage and attribution considerations related to Hunts #2 and #3. His input helped refine the contextual framing around open-source tooling and infrastructure patterns discussed in this report.

Research Overview

Note: This report is the result of a collaborative investigation between Hunt.io and the Acronis Threat Research Unit, where both teams collaborated to map ongoing DPRK infrastructure activity, including Lazarus and Kimsuky.

Throughout the analysis, we surfaced clusters of operational assets that had not been connected publicly before, revealing active tool-staging servers, credential theft environments, FRP tunneling nodes, and certificate-linked infrastructure fabric controlled by DPRK operators.

These findings help outline how different parts of the DPRK operational infrastructure continue to intersect across campaigns and provide defenders with clearer visibility into the infrastructure habits these actors rely on.

Introduction

North Korean state-sponsored attackers run one of the most active operations globally, using hacking for intelligence, revenue, and access. Groups like Lazarus, Kimsuky, and other subgroups make up the DPRK threat ecosystem, each running its own playbook ranging from espionage and financial operations to destructive activities. Despite differences in each group’s playbook and motivation, they often share toolkits such as credential harvesting tools, exhibit similar infrastructure patterns, and rely on comparable delivery lures.

Across their multiple campaigns over the years, DPRK threat actors follow consistent operational patterns that make their activity detectable despite evolving malware and lures. One of the most reliable ways to track these actors is through the infrastructure they leave behind. Even when malware families change, the groups often reuse the same infrastructure from their previous campaign. This pattern makes it possible to pivot across indicators, uncover related infrastructures, tooling, and activity that tie their operations together.

In this research, we used the Hunt.io Threat Actor intelligence to pivot across several DPRK-linked cases to uncover a broader network of DPRK activities. The hunting process is focused on pivoting through IPs, open directories, certificates, and hashes, revealing operator habits across different campaigns. This approach reveals how separate incidents are connected and highlights the consistent operational behaviors of DPRK threat actors.

Fig. 01: Overview of DPRK operational IOCs on the Hunt.io dashboard

Fig. 01: Overview of DPRK operational IOCs on the Hunt.io dashboardOperational Patterns Overview

Across the four hunts, we encountered the same DPRK habits: open directories used as quick staging nodes, repeated deployment of credential theft kits, FRP tunnels running on identical ports across multiple VPS hosts, and certificate reuse that links separate clusters back to the same operators. These patterns stay stable even when the malware or lures change.

From a MITRE ATT&CK perspective, the exposed toolkits fall under Credential Access and Resource Development, the FRP activity aligns with Command and Control, and the certificate pivots reflect the infrastructure choices DPRK groups use for Defense Evasion and long-term access. Once you look at their operations through infrastructure instead of payloads, their workflow becomes much clearer.

These recurring signals are why these clusters can be tracked. Shared hashes, identical directory layouts, certificate patterns, and repeated hosting choices often reveal new infrastructure before it is used in a campaign. The hunts below walk through how these patterns surfaced in practice.

These patterns guided the first hunt into recent Kimsuky and Lazarus activity.

Hunt #1 - Infrastructure Pivoting on DPRK Clusters: Linking Kimsuky and Lazarus Activity

We started hunting DPRK APTs using IOC Hunter, applying the Lazarus Group filter. Then picked up a blog "DPRK's Playbook: Kimsuky's HttpTroy and Lazarus's New BLINDINGCAN Variant" that highlights a recent investigation linked to the Lazarus Group.

Fig. 02: IOC Hunter showing the source article data for 'DPRK's Playbook: Kimsuky's HttpTroy and Lazarus's New BLINDINGCAN Variant'

Fig. 02: IOC Hunter showing the source article data for 'DPRK's Playbook: Kimsuky's HttpTroy and Lazarus's New BLINDINGCAN Variant'Gen Digital's Threat Labs dissected two recent cyber-espionage campaigns conducted by the Kimsuky and Lazarus Group. The first campaign, attributed to Kimsuky, leveraged a VPN-invoice themed ZIP lure to drop a loader ("MemLoad") and a new backdoor dubbed "HttpTroy".

The second, attributed to Lazarus Group, captured a multi-stage intrusion chain culminating in an enhanced version of their BLINDINGCAN remote access tool, signifying the group's continued evolution in obfuscation and stealth.

Using Hunt.io, we tracked one of the IP addresses "23.27.140[.]49" that has an open directory on port 8080. This server was captured by AttackCapture™ on 2025-11-03, prior to other researchers beginning to report related indicators. The open directory shows a single ELF file:

File name: nvd

SHA256:a3876a2492f3c069c0c2b2f155b4c420d8722aa7781040b17ca27fdd4f2ce6a9

Size: 96 KB.

![Fig. 03: AttackCapture™ showing IP 23.27.140[.]49 open directory data on port 8080](https://public-hunt-static-blog-assets.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/12-2025/Inside+DPRK+Operations+New+Lazarus+and+Kimsuky+Infrastructure+Uncovered+Across+Global+Campaigns+figure+3.png) Fig. 03: AttackCapture™ showing IP 23.27.140[.]49 open directory data on port 8080

Fig. 03: AttackCapture™ showing IP 23.27.140[.]49 open directory data on port 8080Upon analysis, the ELF exhibits similar behavior to the BADCALL backdoor that was previously seen in the 3CX supply chain attack by Lazarus. One of these, 23.27.177[.]183, appears in Hunt.io IP intelligence as Lazarus-linked infrastructure and has been observed in prior Lazarus campaigns.

![Fig. 04: Hunt.io IP intelligence data for 23.27.177[.]183](https://public-hunt-static-blog-assets.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/12-2025/Inside+DPRK+Operations+New+Lazarus+and+Kimsuky+Infrastructure+Uncovered+Across+Global+Campaigns+-+figure+4.png) Fig. 04: Hunt.io IP intelligence data for 23.27.177[.]183

Fig. 04: Hunt.io IP intelligence data for 23.27.177[.]183Analysis of New Linux Variant of Badcall Backdoor

The Badcall backdoor has been one of the recognizable malware associated with Lazarus-linked operations. It played a visible part in several of their campaigns over the years, including the 2023 3CX supply-chain attack, where the first Linux version of Badcall was deployed as part of the post-exploitation chain.

This new Linux variant of BADCALL was found being hosted on 23.27.140[.]49. We analyzed the sample and found a small but important update in this variant.

Fig. 05: New Linux Variant of Badcall Backdoor, Main Function

Fig. 05: New Linux Variant of Badcall Backdoor, Main FunctionSimilar to the previous variant of Badcall, the first part of the program checks for a command-line argument, simulates a "kill" command passing the integer specified by the argument as process ID with the Fake_Cmd() function, and proceeds to daemonize itself and start its main operation.

The main difference in this variant is the addition of a log file in the /tmp/ directory named "sslvpn.log". This gives the operators a way to track Badcall's operations using the log file.

Fig. 06: Badcall logMessage() Function

Fig. 06: Badcall logMessage() FunctionThe

logMessage() function writes a timestamped entry into the log file by getting the current local time and writes it in

[YYYY-MM-DD HH:MM:SS] <message> format.

Fig. 07: Xref list of logMessage() function

Fig. 07: Xref list of logMessage() functionThe figure above shows a screenshot of all cross-references from other functions to the logMessage function. This highlights that Badcall now logs its activity across different malware routines.

Fig. 08: Sample logMessage() calls and log entries

Fig. 08: Sample logMessage() calls and log entriesAs seen in the screenshot above, the log entries are short numeric codes that change depending on the operation being done by the malware. This helps the attacker confirm that the malware is running properly and allows them to monitor its behavior throughout the intrusion.

From an operational standpoint, the development of this new Linux variant indicates Lazarus is continuously improving Badcall to better support upcoming operations. Even a small functional update like this can indicate an effort to improve operational efficiency and update their malware arsenal.

Hunt #2 - Lazarus DeceptiveDevelopment Cluster: Credential-Theft Toolkits in Open Directories

While some of the exposed infrastructure dates back to earlier campaigns, its reuse and recurring toolsets remain relevant for understanding current DPRK operational workflows. Recent analysis on the DeceptiveDevelopment campaign revealed a sophisticated Lazarus Group attack disguised as an NVIDIA-themed hiring assessment update. Using the hashes provided in the report as a starting point, we extracted two SHA-256 IoCs of credential-recovery utilities, "MailPassView" and "WebBrowserPassView", both used by the Lazarus group for credential harvesting.

Pivoting over these hashes in Hunt.io AttackCapture™ exposed open directories hosting these tools

Fig. 09: IOC Hunter showing Lazarus group threat actor data

Fig. 09: IOC Hunter showing Lazarus group threat actor dataThe first pivot over MailPassView hash (bc7bd27e94e24a301edb3d3e7fad982225ac59430fc476bda4e1459faa1c1647) in Hunt.io revealed two open directories located at:

| Host | Size | Timestamp |

|---|---|---|

| http://207.254.22[.]248:8800 | 363 KB | - |

| http://149.28.139[.]62:8080 | 363 KB | Sep-12-2023 |

Fig. 10: AttackCapture™ search results for the SHA256 bc7bd27e94e24a301edb3d3e7fad982225ac59430fc476bda4e1459faa1c1647

Fig. 10: AttackCapture™ search results for the SHA256 bc7bd27e94e24a301edb3d3e7fad982225ac59430fc476bda4e1459faa1c1647Analysis for 207.254.22[.]248:8800

This directory, exposed at 207.254.22[.]248:8800, was serving a large credential-theft toolkit, containing 21 files organized into 2 subdirectories, totaling 112 MB. The toolset includes password recovery utilities and extraction tools (MailPassView, PasswordFox, ChromePass.exe, WebBrowserPassView, NetPass, MSPass.exe, Dialupass, PstPassword, IEPV), Large data exfiltration and profile-parsing utilities (hack-browser-data), and a data transfer tool (rclone binaries).

![Fig. 11: AttackCapture™ data 207.254.22[.]248:8800](https://public-hunt-static-blog-assets.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/12-2025/Inside%2BDPRK%2BOperations%2BNew%2BLazarus%2Band%2BKimsuky%2BInfrastructure%2BUncovered%2BAcross%2BGlobal%2BCampaigns%2B-%2Bfigure%2B11.png.png) Fig. 11: AttackCapture™ data 207.254.22[.]248:8800

Fig. 11: AttackCapture™ data 207.254.22[.]248:8800Analysis for host 207.254.22[.]248 shows the IP Address operating under AS30377 (MacStadium, Inc.) in Dublin, Ireland. Hunt.io's intelligence reports it as a Mythic C2 server on port 7443 in August 2025, and the IP has a recorded historical malicious open directory in July 2025, corresponding to the same directory referenced earlier, indicating the infrastructure has been repeatedly used in malicious activities.

![Fig. 12: Hunt.io's intelligence reporting IP 207.254.22[.]248 running a Mythic C2 server on port 7443](https://public-hunt-static-blog-assets.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/12-2025/Inside+DPRK+Operations+New+Lazarus+and+Kimsuky+Infrastructure+Uncovered+Across+Global+Campaigns+-+figure+12.png) Fig. 12: Hunt.io's intelligence reporting IP 207.254.22[.]248 running a Mythic C2 server on port 7443

Fig. 12: Hunt.io's intelligence reporting IP 207.254.22[.]248 running a Mythic C2 server on port 7443Analysis for 149.28.139[.]62:8080

This open directory node hosted at 149.28.139[.]62:8080, exposed a much larger toolkit, consisting of 201 total files, 42 subdirectories, and over 270 MB of content. The files include a Quasar RAT infrastructure (Quasar.exe, Quasar.Common.dll, quasar.p12, profiles, clients, config files), Credential harvesting tools (mailpv.exe, cli.exe, client.bin, multiple DLLs), and File-transfer and persistence utilities (pscp.exe, protobuf-net.dll, etc).

![Fig. 13: Directory view of 149.28.139[.]62:8080 exposing Quasar RAT tooling](https://public-hunt-static-blog-assets.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/12-2025/Inside%2BDPRK%2BOperations%2BNew%2BLazarus%2Band%2BKimsuky%2BInfrastructure%2BUncovered%2BAcross%2BGlobal%2BCampaigns%2B-%2Bfigure%2B13.png) Fig. 13: Directory view of 149.28.139[.]62:8080 exposing Quasar RAT tooling

Fig. 13: Directory view of 149.28.139[.]62:8080 exposing Quasar RAT toolingAnalysis for host 149.28.139[.]62 shows the IP Address is hosted under AS20473 (The Constant Company, LLC / Vultr) in Singapore. Our platform identifies a distinctive Quasar RAT on port 1888 documented between September and October 2023.

![Fig. 14: Hunt.io intelligence showing Quasar RAT activity on 149.28.139[.]62](https://public-hunt-static-blog-assets.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/12-2025/Inside+DPRK+Operations+New+Lazarus+and+Kimsuky+Infrastructure+Uncovered+Across+Global+Campaigns+-+figure+14.png) Fig. 14: Hunt.io intelligence showing Quasar RAT activity on 149.28.139[.]62

Fig. 14: Hunt.io intelligence showing Quasar RAT activity on 149.28.139[.]62Both investigated infrastructure nodes demonstrate clear indicators of malicious behavior. The first host (207.254.22[.]248) shows active 2025 usage, Mythic exposure, and a broad credential-exfiltration suite matching contemporary Lazarus TTPs. The second host (149.28.139[.]62) represents older but relevant infrastructure, containing extensive Quasar RAT tooling and supporting binaries consistent with Lazarus' earlier-stage operations.

Across both servers, the repeated presence of MailPassView, browser credential extractors, and exfiltration utilities demonstrates a persistent DPRK pattern of using open directories as tool staging nodes, enabling rapid deployment during intrusions while maintaining minimal operational friction.

It is important to note that tools such as MailPassView and WebBrowserPassView are legitimate, publicly available utilities and are used by a wide range of threat actors. Their presence alone is not sufficient for attribution. In this case, their relevance comes from their co-location with infrastructure previously linked to Lazarus activity, including historical C2 exposure, repeated reuse of the same hosts, and overlap with known DPRK tradecraft observed in adjacent campaigns.

The pivot over the second hash (36541fad68e79cdedb965b1afcdc45385646611aa72903ddbe9d4d064d7bffb9) reveals two exposed open directories on Hunt.io. The first directory "207.254.22[.]248:8800" is already known from prior tracking and contains a large Quasar RAT operator environment, consistent with previously observed DPRK tradecraft.

![Fig. 15: AttackCapture™ directory listing for 154.216.177[.]215](https://public-hunt-static-blog-assets.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/12-2025/Inside+DPRK+Operations+New+Lazarus+and+Kimsuky+Infrastructure+Uncovered+Across+Global+Campaigns+-+figure+15.png) Fig. 15: AttackCapture™ directory listing for 154.216.177[.]215

Fig. 15: AttackCapture™ directory listing for 154.216.177[.]215Analysis for 154.216.177.215

The host "154.216.177[.]215", operating under AS135377 (LARUS Limited) in Hong Kong, exposes an exceptionally large and sensitive open directory containing 10,731 files, 1,222 subdirectories, and nearly 2 GB of operational data. The files include offensive security tooling (sqlmap, masscan, nmap, hping, tcpdump, ngrok, gost, microsocks, frpc/frps, impacket) and Nuclei (7,820 templates), alongside browser password-stealers, privilege-escalation binaries, packet capture tools, RDP configs, and multiple Python environments.

The presence of development artifacts, Burp Suite keygen links, Privoxy configs, Mimikatz folder stubs, and raw camera-roll/screenshot directories suggests the machine may represent either a compromised Windows workstation or an operator-controlled staging environment repurposed for tooling and development.

The IoC-linked WebBrowserPassView.exe (421 KB) found here aligns directly with the Lazarus DeceptiveDevelopment cluster, and the breadth of tools combined with personal artifacts, logs, and credential-extraction utilities illustrates an active threat actor operations hub, likely used for reconnaissance, credential theft, LPE testing, and offensive development workflows.

![Fig. 16: AttackCapture™ open directory view for 154.216.177[.]215](https://public-hunt-static-blog-assets.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/12-2025/Inside+DPRK+Operations+New+Lazarus+and+Kimsuky+Infrastructure+Uncovered+Across+Global+Campaigns+-+figure+16.png) Fig. 16: AttackCapture™ open directory view for 154.216.177[.]215

Fig. 16: AttackCapture™ open directory view for 154.216.177[.]215Once the pivots move from payloads to infrastructure, the separation between DPRK subgroups becomes less distinct and shared operational habits start to surface.

Hunt #3 - Lazarus FRP Infrastructure Hunt - 3CX Supply Chain Linkage

From IOC Hunter, we picked up another article titled "Three Lazarus RATs coming for your cheese", which highlights the use of Fast Reverse Proxy (FRP) within DPRK-linked APT campaigns.

This directly aligns with earlier findings from 2023, when Google Cloud's threat intelligence team analyzed the 3CX software supply-chain compromise and discovered that the Lazarus Group had incorporated FRP components into their multi-stage intrusion chain.

Across DPRK-linked intrusions, FRP usually sits between the compromised host and the operator, giving Lazarus a dependable way to maintain access even when outbound traffic is filtered or restricted.

FRP itself is an open-source tunneling framework and is widely used across many threat ecosystems, including multiple Chinese APT groups. Its use here is not treated as a unique Lazarus indicator. Instead, the attribution signal comes from the consistent deployment pattern observed across multiple VPS nodes, identical binaries served on the same port, and its alignment with infrastructure previously tied to Lazarus operations, including those documented during the 3CX incident.

While FRP is typically deployed internally within victim environments, its repeated exposure as internet-facing infrastructure in this cluster represents an operational choice that differs from benign usage patterns.

In that incident, the attack began with a trojanized 3CX desktop client and progressed through several stages of compromise, marking one of the earliest publicly observed uses of FRP by Lazarus. Together, these insights reinforce the group's continued reliance on FRP tooling across different campaigns and timelines.

Fig. 17: IOC Hunter entry for the FRP-related Lazarus campaign

Fig. 17: IOC Hunter entry for the FRP-related Lazarus campaignPivoting on the FRP hash 24d5dd3006c63d0f46fb33cbc1f576325d4e7e03e3201ff4a3c1ffa604f1b74a, Our platform surfaced eight hosting instances (182.136.123[.]102, 119.6.56[.]194, 182.136.120[.]52, 118.123.54[.]71, 61.139.89[.]11, 125.67.171[.]158, 125.65.88[.]195, and 119.6.121[.]143) over the same port "9999".

Fig. 18: AttackCapture™ results for FRP hash 24d5dd3006c63d0f46fb33cbc1f576325d4e7e03e3201ff4a3c1ffa604f1b74a

Fig. 18: AttackCapture™ results for FRP hash 24d5dd3006c63d0f46fb33cbc1f576325d4e7e03e3201ff4a3c1ffa604f1b74aThe uniformity across these nodes is notable. All eight servers returned the same FRP binary, with identical file size and configuration patterns. This consistency suggests that the operators are provisioning these nodes in a scripted or automated way, rather than configuring each server manually.

Each node served a 10 MB FRP binary, indicating widespread deployment of identical tunneling infrastructure likely used to proxy internal footholds back to operator-controlled servers.

This pattern strongly aligns with Lazarus Group's operational practice of deploying uniform FRP instances across rotating Chinese and APAC-region VPS hosts to support covert C2 communications in extended campaigns. FRP gives the operators a stable way to maintain access even when more traditional C2 channels are blocked or sinkholed.

The concentration of these nodes on regional VPS providers, mostly within the same geographic footprint, matches earlier Lazarus clusters that relied on inexpensive and short-lived infrastructure. Running multiple identical FRP nodes in parallel also hints at simultaneous operations or at a rotating pool of redirectors used to support different intrusion paths.

Hunt #4 - Pivoting Into APT Lazarus Certificate

The hunt began by selecting the domain secondshop[.]store from Hunt.io's IOC Hunter using the Lazarus Group filter.

![Fig. 19: IOC Hunter showing secondshop[.]store linked to Lazarus Group](https://public-hunt-static-blog-assets.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/12-2025/Inside+DPRK+Operations+New+Lazarus+and+Kimsuky+Infrastructure+Uncovered+Across+Global+Campaigns+-+figure+19.png) Fig. 19: IOC Hunter showing secondshop[.]store linked to Lazarus Group

Fig. 19: IOC Hunter showing secondshop[.]store linked to Lazarus GroupThe domain resolved to the IP Address "23.254.128[.]114" which is the part of AS54290 (Hostwinds LLC.). According to our data, the IP carried a High-Risk reputation with explicit labeling as Lazarus Group, and exhibited historical TLS/HTTP activity on port 443, consistent with typical Lazarus infrastructure patterns.

![Fig. 20: Hunt.io IP intelligence for 23.254.128[.]114](https://public-hunt-static-blog-assets.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/12-2025/Inside+DPRK+Operations+New+Lazarus+and+Kimsuky+Infrastructure+Uncovered+Across+Global+Campaigns+-+figure+20.png) Fig. 20: Hunt.io IP intelligence for 23.254.128[.]114

Fig. 20: Hunt.io IP intelligence for 23.254.128[.]114To widen the view beyond a single domain, we pivoted from the certificate associated with the IP using the field subject.common_name == "hwc-hwp-7779700" using HuntSQL query. The result shows 12 IP Addresses all exposed with port 3389 since January 2025.

SELECT

ip,

port

FROM

certificates

WHERE

subject.common_name == "hwc-hwp-7779700"

AND timestamp gt '2025-01-01'

GROUP BY

ip,

port

CopyExample output:

Fig. 21: HuntSQL results showing 12 IPs tied to certificate subject "hwc-hwp-7779700"

Fig. 21: HuntSQL results showing 12 IPs tied to certificate subject "hwc-hwp-7779700"The consistent exposure of RDP across these hosts suggests they are not passive servers but systems intended for operator access or staging. This behavior aligns with earlier Lazarus infrastructure, where exposed RDP has repeatedly been used for operator logins and hands-on management of distributed C2 nodes.

To validate whether these IPs were linked to actual malicious operations, we queried our Hunt.io malware database for all 12 IP addresses. The results show that ten of the queried IPs were directly associated with "Lazarus Group" malware on port 443, confirming active operational infrastructure.

SELECT

ip,

port,

malware.name

FROM

malware

WHERE

(

ip = '104.168.198.145'

OR ip = '23.254.164.50'

OR ip = '192.236.146.20'

OR ip = '142.11.209.109'

OR ip = '192.119.116.231'

OR ip = '192.236.233.162'

OR ip = '192.236.176.164'

OR ip = '192.236.236.100'

OR ip = '192.236.146.22'

OR ip = '23.254.128.114'

OR ip = '192.236.233.165'

OR ip = '104.168.151.116'

)

AND timestamp gt '2025-01-01'

GROUP BY

ip,

port,

malware.name

CopyOutput example:

Fig. 22: Malware dataset results correlating 10 of 12 certificate-linked IPs to Lazarus samples

Fig. 22: Malware dataset results correlating 10 of 12 certificate-linked IPs to Lazarus samplesThe remaining two IP addresses, 104.168.151[.]116 and 192.119.116[.]231, were manually enriched using Hunt.io's asset intelligence. Both belonged to Hostwinds' Seattle infrastructure with multiple pivots linking them to Bluenoroff (APT38) tracking campaigns.

The overlap with Bluenoroff at this stage is meaningful. Even though Lazarus and Bluenoroff operate with different mission profiles, shared infrastructure elements like certificates or hosting providers often suggest where their operational workflows may intersect. These small overlaps act as early markers of broader DPRK ecosystems that remain active behind individual campaigns.

Fig. 23: Hostwinds infrastructure node with pivots into Bluenoroff-linked activity.

Fig. 23: Hostwinds infrastructure node with pivots into Bluenoroff-linked activity.![Fig. 24: Asset intelligence enrichment for 104.168.151[.]116](https://public-hunt-static-blog-assets.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/12-2025/Inside%2BDPRK%2BOperations%2BNew%2BLazarus%2Band%2BKimsuky%2BInfrastructure%2BUncovered%2BAcross%2BGlobal%2BCampaigns%2B-%2Bfigure%2B24.png) Fig. 24: Asset intelligence enrichment for 104.168.151[.]116

Fig. 24: Asset intelligence enrichment for 104.168.151[.]116The analysis confirms that the secondshop[.]store acts as an entry point into a much broader and still-active Lazarus ecosystem, revealing both mature C2 nodes and auxiliary proxy infrastructure.

These observations point to a few concrete signals defenders can use to stay ahead of this activity.

Defender and Hunting Guidance

The infrastructure uncovered across the four hunts highlights several reliable signals defenders can use to track DPRK activity, even when payloads or lures shift.

Open directory exposure

Multiple staging servers hosted credential theft tools, Quasar environments, Linux backdoors, rclone binaries, and offensive toolkits. These directories tend to recur across different nodes with almost identical layouts. Monitoring for exposed directories that contain these repeating toolsets can reveal new infrastructure tied to the same operators.

Repeated FRP deployments

The same FRP binary appeared across eight VPS hosts, all serving the same 10 MB file on the same port. This creates a predictable footprint that can be monitored across providers where DPRK operators tend to host infrastructure.

As with other open-source tooling, FRP should be evaluated in combination with deployment patterns, hosting context, and historical infrastructure reuse rather than treated as a standalone attribution signal.

Certificate reuse

The Lazarus-linked certificate that surfaced twelve IP addresses showed how certificate pivots can expose entire infrastructure clusters. Tracking newly exposed hosts that reuse the same certificate profile or appear on the same RDP or TLS ports can uncover new operational nodes before they are used in active campaigns.

Historical telemetry on shared VPS providers

Throughout the hunts, the same hosting providers reappeared in different campaigns. Watching for recurring combinations of provider, certificate profile, port exposure, and FRP artifacts can help surface new infrastructure even before malware begins communicating with it.

These signals help defenders move from reactive identification of DPRK activity to a more proactive view of how the operators prepare and maintain their infrastructure.

Conclusion

Across all four hunts, the same operational habits kept surfacing. The FRP nodes deployed in identical configurations, the recurring credential-theft toolkits exposed in open directories, and the reuse of certificates and VPS providers all point back to a tightly patterned workflow inside the broader DPRK ecosystem. These stable behaviors make their infrastructure easier to track than the shifting payloads or lures used in individual campaigns.

For defenders, the signals that consistently appeared in this investigation remain the most reliable: repeated FRP binaries on port 9999, credential harvesting kits staged on exposed HTTP directories, certificate subjects reused across clusters of RDP-enabled hosts, and infrastructure repeatedly provisioned through the same regional providers. Watching for these patterns gives teams an advance look into DPRK activity as it forms, not only after an intrusion is underway.

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)

The following list gathers all indicators surfaced during the hunts, including hashes, infrastructure nodes, and associated DPRK-linked assets.

| IOCs | Description |

|---|---|

| a3876a2492f3c069c0c2b2f155b4c420d8722aa7781040b17ca27fdd4f2ce6a9 | New Linux Variant of Badcall Backdoor |

| cc307cfb401d1ae616445e78b610ab72e1c7fb49b298ea003dd26ea80372089a | Old Linux Variant of Badcall Backdoor |

| a5350b1735190a9a275208193836432ed99c54c12c75ba6d7d4cb9838d2e2106 | Poolrat |

| ff32bc1c756d560d8a9815db458f438d63b1dcb7e9930ef5b8639a55fa7762c9 | Poolrat |

| 85045d9898d28c9cdc4ed0ca5d76eceb457d741c5ca84bb753dde1bea980b516 | Poolrat |

| bc7bd27e94e24a301edb3d3e7fad982225ac59430fc476bda4e1459faa1c1647 | MailPassView |

| 36541fad68e79cdedb965b1afcdc45385646611aa72903ddbe9d4d064d7bffb9 | WebBrowserPassView |

| 24d5dd3006c63d0f46fb33cbc1f576325d4e7e03e3201ff4a3c1ffa604f1b74a | FastReverseProxy |

| 23.27.140[.]49:8080 | Badcall Host URL |

| 23.27.177[.]183 | Badcall C2 server |

| 23.254.211[.]230 | Badcall C2 server |

| 207.254.22[.]248:8800 | Opendir |

| 149.28.139[.]62:8080 | Opendir |

| 154.216.177.215:8080 | Opendir |

| 182.136.123[.]102:9999 | FRP Host URL |

| 119.6.56[.]194:9999 | FRP Host URL |

| 182.136.120[.]52:9999 | FRP Host URL |

| 118.123.54[.]71:9999 | FRP Host URL |

| 61.139.89[.]11:9999 | FRP Host URL |

| 125.67.171[.]158:9999 | FRP Host URL |

| 125.65.88[.]195:9999 | FRP Host URL |

| 119.6.121[.]143:9999 | FRP Host URL |

| secondshop[.]store | Lazarus-linked pivot domain |

| 23.254.128[.]114 | Lazarus certificate-linked infrastructure |

| 104.168.198[.]145 | Lazarus certificate-linked infrastructure |

| 23.254.164[.]50 | Lazarus certificate-linked infrastructure |

| 192.236.146[.]20 | Lazarus certificate-linked infrastructure |

| 142.11.209[.]109 | Lazarus certificate-linked infrastructure |

| 192.236.233[.]162 | Lazarus certificate-linked infrastructure |

| 192.236.176[.]164 | Lazarus certificate-linked infrastructure |

| 192.236.236[.]100 | Lazarus certificate-linked infrastructure |

| 192.236.146[.]22 | Lazarus certificate-linked infrastructure |

| 192.236.233[.]165 | Lazarus certificate-linked infrastructure |

| 192.119.116[.]231 | Lazarus infrastructure with Bluenoroff overlap |

| 104.168.151[.]116 | Lazarus infrastructure with Bluenoroff overlap |

Detection by Acronis

As part of this joint work, the Acronis Threat Research Unit reviewed the activity described in this report from the endpoint perspective. Their EDR/XDR telemetry surfaced the same behaviors seen in the infrastructure layer, including the latest Badcall variant, credential harvesting tools, and several of the Lazarus-linked nodes highlighted above.

This gives an additional confirmation path: the infrastructure we observed being prepared and used by DPRK operators also appeared as endpoint-level detections inside Acronis' visibility. It reinforces the relationship between the external infrastructure pivots and the on-host activity defenders may see during similar intrusions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Daniel Gordon for his peer review and analytical feedback on tooling usage and attribution considerations related to Hunts #2 and #3. His input helped refine the contextual framing around open-source tooling and infrastructure patterns discussed in this report.

Related Posts

Related Posts

Related Posts